|

This story starts at Valentia Island in Ireland which must be viewed as the cradle of ocean telegraphy. The ‘old man’, James Graves, had been the superintendent there from 1866 to 1909 and had founded both a professional and family dynasty. Operators that he had trained were to be found all over the world. His family was large and in the way in which relationships at these stations worked his grand-daughter, Nan (centre in this picture), married the son of William Hearnden who had succeeded him as superintendent. Their middle son was the father-in-law of this author. The other two girls in the picture also married station staff.

|

Their youngest brother, who was almost of the same age as Nan’s eldest son was Walter (Wallie), shown here with his cousin, Ada.

Wally was on the staff at Valentia Island and in the period up to 1922 he was a punching clerk who prepared tape for insertion into the high-speed transmitters. This was labour intensive and the staff level at the station at the end of the first world war was approximately 300.

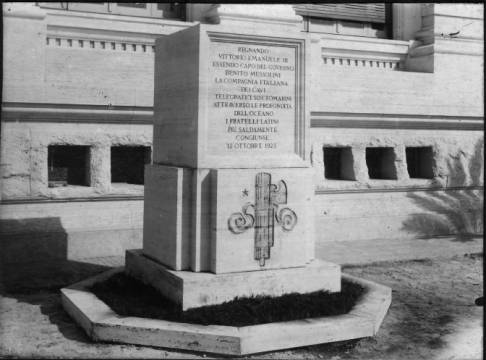

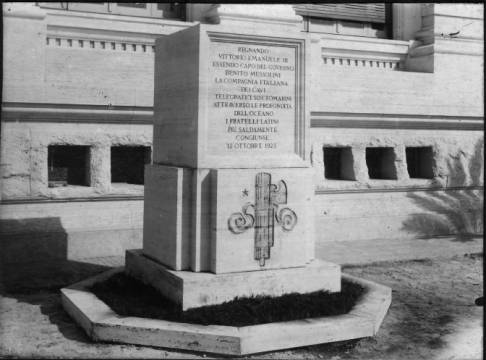

The first world war had been a traumatic experience for all in the telecommunications business. The capacity of the cables simply was not up to the demand and if one was damaged, the threat of a U-boat attack made repair almost impossible. In the latter part of the war staff were working 16 hour days and when one cable went out of service it came as a relief to all, even if not to the customers for whom communications was critical. Something had to be done and something was going to be done. The re-allocation of the entire German communications infra-structure as reparations to the Allied nations as part of the Treaty of Versailles was a start. In this carve-up the cable-laying ship GrossHerzog (Archduke) von Oldenburg was handed over to Italy where it was renamed the Citta di Milano (City of Milan).

The cableship Citta di Milano (City of Milan) which was previously

the GrossHerzog von Oldenburg of the German cable company and

ceded

to

Italy after the Treaty of Versailles as part of war reparations |

There were also significant advances in technology and by the mid 1920s high-speed cables which were the forerunners of analogue telephone cables were introduced. The other major innovation was telex. This was well established on land-lines but there were major difficulties with sea cables which were not overcome until about 1918. Everything was ready to introduce telex in about 1922 when the civil-war which followed Irish independence caused major disruptions. All but a relatively small number of the Atlantic cables went via Ireland and these were either damaged or the connecting land-lines were cut by Republican forces. The end result was that for several weeks the communications between the trade centres of Europe and North America were returned to what they had been before 1866.

Even when some normality had returned in September 1922 it was uncertain whether telex on cables would succeed. Operators were so skilled at ‘short-form’ codes that it was possible to get an extraordinary level of information compression that would not be possible with telex. Nevertheless telex was introduced and there was a consequential decimation of staff. Amongst those made redundant by Western Union (who had operated the cables since 1911) was Wallie Graves. Consequently, he and many other skilled operators were available at just the moment when Italy was in the process of establishing its independence in the world of communications.

Western Union staff operating telex machines with a multiplexer in the right foreground. To the right of the operator on the left one can see ‘slip’: the punched tape that was fed to the transmitter |

Italcable was founded in 1921, but it took some years to get going. Most of the pictures below are from the Wallie Graves’ photo album (which is now in the possession of Fred Hearnden). These show that a group of operators travelled to Italy from Britain in 1925, taking a boat from Dover to Boulogne on 23 November of that year. There is a picture that shows Marshall Killen and Mr Partington on board a small ship that also has a Rolls Royce on its deck. They may have driven to Italy, because there is a photo entitled “view between Modane and Torino near the Italian Frontier 24/11/25” and there are other pictures of St Peter’s, Rome dated 25/11/25.

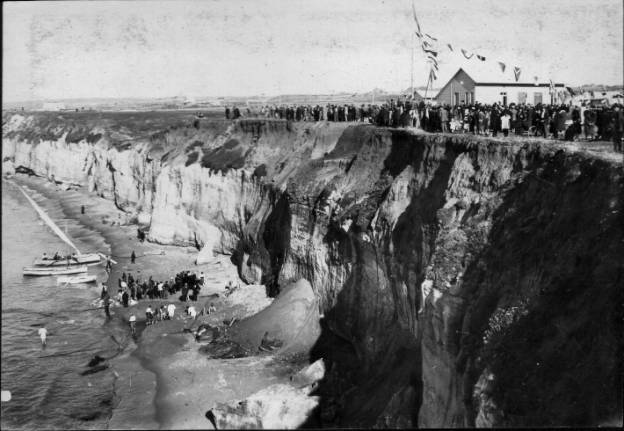

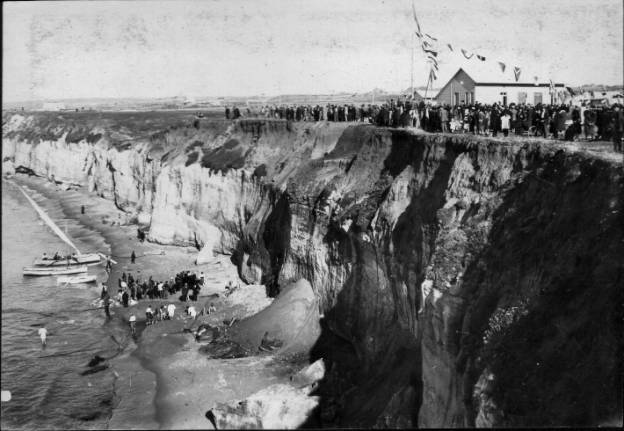

The heavy shore-end cable being offloaded from the ship

(Citta di Milano?),

held up with floats and being towed ashore. |

|

|

|

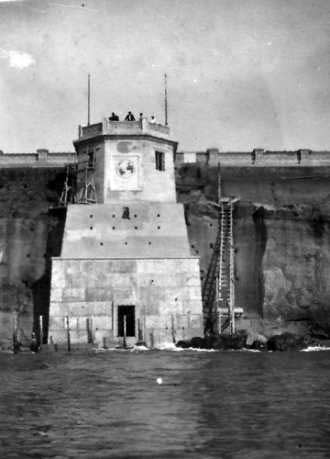

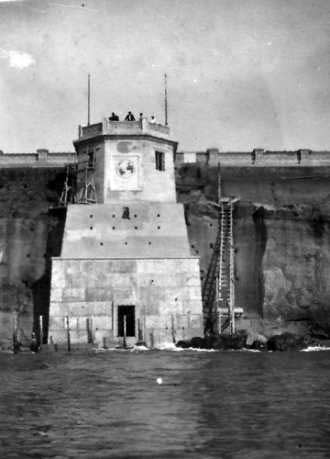

View from the mouth of the tunnel |

View of cable tunnel protection in progress and the new station in the background |

View of the completed cable entrance on the beach at Anzio |

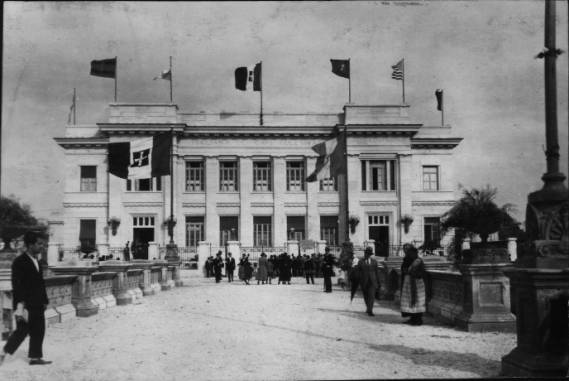

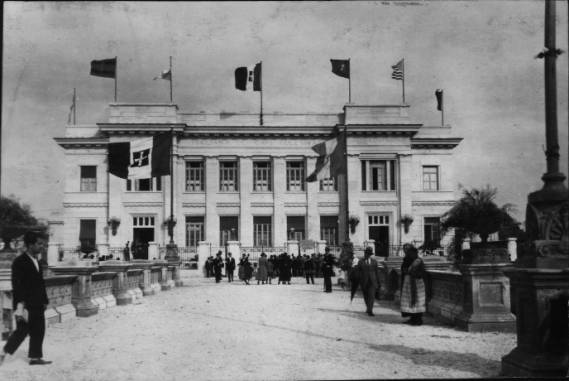

Cable station at Anzio |

|

The Anzio office gardens |

It is possible that many of these photographs were taken before the arrival of the cable staff, some of whom are shown below.

Probably the manager or senior technical person, as he is referred to as Mr Partington in the photo album. |

Operators (?) Bennett and Kerkin |

Marshall Killen (who was Supt at the Western Union Azores station at closure in 1966).

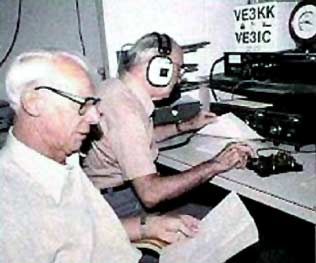

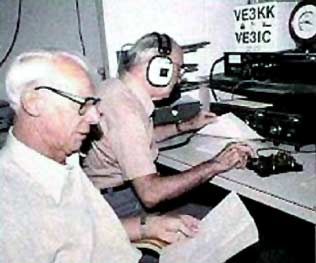

Killen was a radio amateur and this picture shows him at his kit in Anzio in 1926.

|

This author met Marshall Killen at his home in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada in 1985 and this picture showing Killen at his key is exactly as he remembers him |

It is not clear how long Killen spent at Anzio. He was an electrician rather than an operator and perhaps he had some part in advising on the working of the cable which ran to Malaga and from there to Horta, Azores, where traffic was merged with the high-speed Western Union cables to the United States. Killen may have been ‘lent’ by Western Union because very shortly afterwards he was based at Horta.

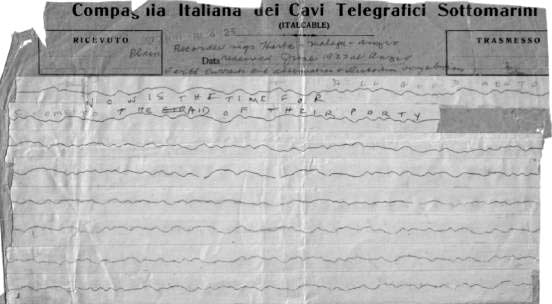

The record shown below, which is in the possession of this author, is a copy of the print-out from the Kelvin siphon recorder (the original bubble-jet printer) of a message transmitted at Horta and received at Anzio. The interpretation of this, which contained a severely attenuated signal with superimposed earth-currents and other artefacts, is a witness to the skills of operators.

This author was on a Royal Society funded research visit to St Johns, Newfoundland in March/April 1985 and during this time he visited the Maritime History Archive at Memorial University where he discovered a large collection of documents that found their way there from Western Union’s New York Headquarters. Someone had retrieved them from being thrown in a dumpster and thought that they might be of interest to this new initiative of the late Keith Matthews.

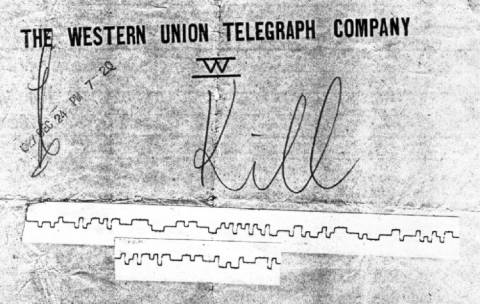

While searching through these papers he discovered the record shown below, which shows how much the technology had developed within a few months. The signal has been through a Western Union regenerator and shows none of the defects of the message above. Signals had to be of this quality for the system to be amenable to telex operation.

However, the message itself contains other fascinating details. It was clearly intended for Marshall Killen and if one interprets everything above the central line as a dot and everything below the line as a dash it reads:

TTE KIL HO II MERRY XMAS TO U AND ALL II WG  (27 December 1927) (27 December 1927) |

This translates as “transmit to Killen Horta (start of message) MERRY XMAS TO U AND ALL (end of message) WG (sender) (end of transmission)”. WG was, of course, Wallie Graves. A copy of this was carried from Newfoundland when this author travelled to Kitchener, Ontario to meet with Killen during Easter 1985. Killen was naturally fascinated how such a piece of paper travelled from Horta to New York in 1966 when Western Union closed its Azores station, and from there to St Johns, Newfoundland.

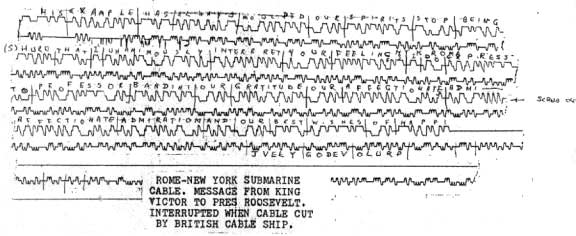

The friendship between Graves and Killen always remained very strong and when Mussolini removed all non-Italian staff from Anzio, Killen was able to get him a job with Western Union in the Azores. Family photographs from the Azores include pictures of the great flying events and include shots of most of the aviators including Lindberg. Both spent the period of the second world war there. Killen was electrician on duty the night that Italy entered the war and he was able to ‘pinch’ the recorder copy of the messages in transit on the Italian cable at the exact instant of the cutting as can be seen below.

As Killen handed the Azores intercept to the author he said:

“You must understand that the Azores was a regeneration (signal restoration) station with each cable working in duplex (messages simultaneously in both directions). At the end of each cable we had a recorder which showed the passing traffic (in cable-code). Thus there was one on the east side for the cable between the Azores and the next regeneration station (Malaga). There was also one on the west side for the cable between the Azores and New York. I was on duty at the east side as the message from the King to President Roosevelt was going through and retained the internal record or slip as it came off the Recorder. The slip (figure1) shows two messages: the ‘incomer’ is a bit indistinct but is in-clear (not enciphered) and the ‘outgoer’ or reconstituted signal which is in five-character cipher. It is easy to read the outgoer. Each pulse above the centre line is a dot and each pulse below is a dash. Because of distortions on the cable the incomer is more difficult and you must judge the number of dots or dashes by the length of a group. You can see the exact point at which the cable has been cut and you can also see that New York, unaware of this, continues to transmit”

Inspection of the incomer reveals that it is as Killen described, However, the outgoer is particularly interesting as it reveals the rapid transmission of several messages, including one in cipher. The first appears to be a service call-up message and like the others it is terminated by the Morse characters S and N run together as (dit dit dit dah dit and designated as  ). Each has a header which comprises a service code presumably designating addressee and any other information and terminated by a break or equals sign ( dah dit dit dit dah). The second message is in-clear, but uses codes (e.g. PC44). The third message is in five character cipher. The fourth is incomplete. ). Each has a header which comprises a service code presumably designating addressee and any other information and terminated by a break or equals sign ( dah dit dit dit dah). The second message is in-clear, but uses codes (e.g. PC44). The third message is in five character cipher. The fourth is incomplete.

Translation of the ‘incomer’ (author’s notes lower case between parentheses):

HIS EXAMPLE HAS ALWAYS MOULDED OUR SPIRITS STOP BEING

(s)HURE THAT I UNANIMOUSLY INTERPRET YOUR FEELINGS I DO EXPRESS

TO PROFESSOR BANDINI OUR GRATITUDE OUR AFFECTIONATE ADMIR (delete)

AFFECTIONATE ADMIRATION AND OUR BEST WISHES OF HAPPI ________ _ _ _ |

(the line indicates the point at which the cable has been cut)

Literal translation of the ‘outgoer’ (author’s notes lower case between parentheses):

.(full stop) .(full stop) RK RK F F F DF DF DF DF  STC PU6 NYK ROMA4 = STC PU6 NYK ROMA4 =

PC44 TREASAMEX SIGNATURE REQUIRED  KCPA3 CDE NYK A7 AA AAE7 KCPA3 CDE NYK A7 AA AAE7

A ROMACAMBI ROMA = GREFO YGLDO AGLMY APOSY UFEOB VLORA UF

APO XUOPE IADID IUPYC GOPIA JVELY GODEV OLURP JVEGT  NRANN NRANN

NYK UN AA NLT (lost under Killen’s stick-on label of explanation) (?) RNRI VIA RODI 27 |

Contextual translation of the ‘outgoer’ (author’s notes lower case between parentheses):

. . RK RK F F F DF DF DF DF

STC PU6 NYK ROMA4

= PC44 TREASAMEX SIGNATURE REQUIRED

KCPA3 CDE NYK A7 AA AAE7A ROMACAMBI ROMA

= GREFO YGLDO AGLMY APOSY UFEOB VLORA

UFAPO XUOPE IADID IUPYC GOPIA JVELY GODEV OLURP JVEGT

NRANN NYK UN AA NLT (obliterated) (?) RNRI VIA RODI 27 (end of record) |

It is believed that the cable between Malaga and Horta was cut in the Straits of Gibraltar by CS Iris. The cable between Italy and Spain would of course have been protected by international law. According to Killen the interrupted cable was used by the Americans when they landed in North Africa and there is certainly a record that there was at least one cable ship in the invasion fleet. Up to that time all US government traffic went via Western Union, who on account of the nature of their landing licenses in the UK were bound to make all traffic travelling on their cables via Britain available to British censors. The Americans were clearly unhappy that their conduct of the war could be monitored by Churchill and so the requisitioned Italian cable gave them a bypass link.

The author met Walter Graves and his wife at Bangor, Northern Ireland in 1971. Even then his memory was already failing him. Apart from the photographs from his albums, all anecdotal information about the early history of the Anzio cable must be attributed to Marshall Killen, to whom this author is indebted.

Editor's Note: Many of Donard de Cogan's papers on the history of telegraphy and undersea cables are now available on his website [archive copy].

See also the main page on Italcable. |