|

Introduction: Katherine Swinney shares this

information on her father, Alexander Purse Murdoch, who served on CS Faraday (2) in the 1920s and 30s.

Of particular interest is a report written by Murdoch about the 74-day excursion of CS Faraday (2) to repair cables in the North Atlantic following the major undersea earthquake of 18 November 1929, which disrupted twelve submarine cables in the Grand Banks area off Newfoundland. The repair operations were conducted by all the affected cable companies working in cooperation with each other; the cableships All America, John W. Mackay and Lord Kelvin were also involved.

The full text of Alexander Murdoch’s report is reproduced below, very lightly edited for punctuation and spelling. I have also added contemporary images of the ships mentioned. As noted in the captions, some of the images are courtesy of Brian Ellis, whose father Leonard Ellis also sailed on this expedition. Further details and additional photographs may be seen on the Cable Stories page for Leonard Ellis.

|

Katherine Swinney writes:

My father, Alexander Purse Murdoch, was born on the 26th January 1914 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The Murdochs had emigrated from Scotland and settled in Belfast, Co. Antrim, during the Plantation of Ulster initiated in 1609 by James I, and I know that my great-great-grandfather James Murdoch was a farmer somewhere in Co. Antrim.

My great-grandfather, Alexander Murdoch, chose a very different career by becoming a builder, and passed this business on to his son Charles Murdoch, my grandfather.

My father came from a very comfortable background, as his father’s building business was very successful. He was the eldest of three children, and attended the highly-regarded Rossall School in Fleetwood, Lancashire. The school was the first in Britain to have a cadet corps, established there in 1860, one branch of which was the Sea Cadet Corps. According to a later record, Alexander had been a cadet at the school.

While he was at Rossall, at not quite 16 years of age, he joined the cable ship Faraday on her 1929-30 voyage to repair the North Atlantic cables. As a cadet this would have been an exciting opportunity for him, and the fact that the ship’s captain, Robert Allan, was also Alexander’s “Uncle Bobbie” would have been another impetus for him to sail on this expedition. He typed a report on the events of that voyage which is reproduced below.

In 1935, when he would have been 21, he sailed again on CS Faraday. A letter dated 14 July 1935 from Captain Allan to Alexander Murdoch reads in part:

“Time is getting short now and as near as I can tell you we leave on Sept 7th but I shall probably want you aboard 2 or 3 days before that as Steve will have a good deal to do. No 1 (that is the Chief Petty Officer) will be rushed to death and will be glad of all the assistance he can get.”

I believe that 1936 was the last time he went to sea. On returning to Ireland he became a partner in a firm of estate agents and valuers, Brian Morton & Co in Belfast. The date when he joined the company is unknown, but legal records show that the partnership was dissolved on 5 August 1938. After that he set up his own Estate Agency in the centre of Belfast, which became successful and well known for the next 30 years or so. The successor to the company remains in business today as Agar Murdoch & Deane. Alexander used to joke that all he had to start his business was an old rusty typewriter, an old hat and £5!

The online Encyclopedia of Newtownards 5th. Light Anti-Aircraft Battery records that Alexander Purse Murdock was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Searchlight Regiment on 1 April 1939. During the Belfast Blitz of April and May 1941, he was a very active volunteer in the Belfast Fire Brigade, and was out every night during that very dangerous time

I think that his time at sea was the start of his love of the water, as he spent the rest of his life very involved in sailing at Strangford Lough Yacht Club, Co. Down, Northern Ireland. He used to go on cruises with friends, either in his own yacht or theirs, before getting married in the early 1940s, and during his lifetime he had more than one yacht of his own, which were always moored at Strangford Lough. As a family we used to go off in the School Summer holidays and sail up the West Coast of Scotland, getting as far as Tobermory. His family was the crew – my mother, myself and my two sisters!

He retired in his mid fifties and died in January 2002, a few days before his 87th birthday. Apparently the Scottish name Murdoch means seaman or mariner, so it was a fitting name for someone who loved the sea so much. I know that one of his favourite hymns was Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar” (Hymn 687)

Alexander Purse Murdoch

Report of

N. Atlantic Repair for Commercial Cable Co.

by

C.S. Faraday 1929-30. |

Orders were received for the Faraday to prepare for sea on Wednesday, 20th November [1929]. By the afternoon of Monday 25th November she was ready, having in that time engaged a full complement of Officers and Crew, taken in deck, cable engine, and steward’s stores, and 156 miles of cable besides 750 tons of sand ballast and 300 tons of fresh water. Owing to weather conditions she was unable to leave the West India Docks by that night’s tide but left at 7.20 the next morning, 26th November.

All went well until 11.30 a.m. on the 27th when a serious accident occurred. Three of the Engineer’s staff were badly burnt from a back-flash while cleaning out boiler tubes. One of the men, R. Lea, boilermaker’s mate, was so severely injured it was deemed advisable to put into Plymouth to land him. This was done at 4.30 p.m. the same day. The injured man had hardly been hoisted over the side into the Agent’s Launch before two further casualties were reported, but as they were not considered sufficiently serious to land, the ship proceeded at 10.58 p.m. Almost immediately after clearing the Channel bad weather was encountered. Hitherto the Faraday had never been really tested as to her bad weather capabilities. She was destined to be thoroughly tested in this respect during the forthcoming expedition.

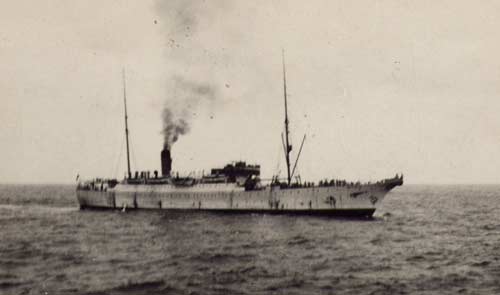

/RLF/Faraday-01_s.jpg)

CS Faraday (2) shortly after her launch in 1923 |

The weather got steadily worse and on the night of 1st Dec. the 100 miles p.h. gale which subsequently swept over the British Isles was at its height. The ship fulfilled all expectations and weathered the storm in the most wonderful way, not, however, without some scars of battle. The two sheaves of the bow baulks had been badly damaged by the terrific pounding also the forepeak bulkhead strained. All the bow baulk and stern telegraphs were broken and all but one rendered useless besides other minor damage.

The gales continued with varying force all the way across, rendering progress painfully slow, and it was not until 5 p.m. on 9th December that the pre-arranged rendezvous with the C.S. John W. Mackay in Lat 44° 58’ N, Long 55° 05’ W was effected. Orders were to co-operate with the Commercial Cable Company’s ship in repairing the Main 6 Azores - Canso Cable.

For some days during the passage across, the condition of T. Haley, one of the injured firemen, had been causing grave anxiety, so in order to save his life permission was asked and obtained from New York to proceed to St Johns N.F. to land him. Port was reached on 10 p.m. on the 10th December and Hayley landed. The opportunity was taken to replenish with medical and other requisite supplies, also officers and crew were able to provide themselves with more suitable warmer clothing in the way of woolen caps and gloves, etc., to cope with the cold which was far more intense than they had anticipated.

The Cablegrounds were reached again just after midnight of the 11th, the weather in the meantime had been so severe that the John W. Mackay had been unable to do any work, so fortunately no time had been lost.

Work was commenced on the 13th Dec. in Lat 44° 46½ N, Long 56° 13W, in a depth of approximately 500 fathoms. The first operation on orders from N.Y. was to pick up the John W. Mackay Canso buoyed end of the Main 6, which had been reported a dead earth. It was found, however, to be O.K., but the seal broken. This was renewed and the end again buoyed. Then the instructions were received to recover the Canso end of Main 4 and for several days grappling operations were carried out without success. From all indications the cable was buried.

On 16th Dec. fresh instructions were received from the J.W.M. to transfer operations to the eastern end of Main 6 as he was proceeding to Halifax. One abortive drive was made, using the Lucas cutting grapnel, when information came from the All America who had arrived on the same and had recovered the Eastern end of Main r4, and was splicing on. The Faraday was accordingly ordered to proceed to the position where she would buoy her end, pick it up, splice on, and pay out to the J.W.M.’s Canso buoyed end of main 6 in order to get one main cable working. Unfortunately this plan miscarried owing to the drum rope, a new 4 x 4, parting when picking up the All America buoyed end in heavy weather. A mark buoy was put down and grappling operations began at once to recover the end, but misfortunes continued, for though cable was hooked the first drive in 1450 fathoms, it proved to be the section of Main r4 just abandoned by the All America.

CS All America |

Prospects were looking gloomy for getting anything done before Christmas and a sense of depression was felt throughout the ship at the run of ill luck, but on Christmas Eve cable was hooked and brought safely to the bows and tested O.K. to Azores. But the weather was never suitable for cable work for many hours together, and again grew so bad it was decided to buoy. This was successfully done in Lat. 44° 25½ N, Long 55° 16 W.

That night the wind increased to almost hurricane force and continued over Christmas Day, but despite of wind and weather a more cheerful Christmas was spent by the Ship’s Company than otherwise would have been the case. All felt something had been done.

On 28th December the J.W.M. returned from Halifax, bringing mails and stores for the Faraday As soon as these had been transferred the Faraday set off, weather having moderated, to pick up her Main r4 cable buoy, but fate was still unkind. The buoy had been carried away during the storm.

CS John W Mackay. The speck in the water by the bow is a small boat from CS Faraday (2),

sent over to get mail and fresh stores during the repair of cables damaged in the North Atlantic earthquake of November 1929.

Image courtesy of Brian Ellis |

The end was recovered again on 27th December and spliced on to the ship’s stock in Lat. 44° 22½ N, Long 55° 16¼ W, and 55 miles paid out towards the All America’s Canso end of man r4. Fog came down again while paying out and the end had to be buoyed without sighting the All America’s buoy.

During all operations hitherto all sun and star observations had been very few and far between so the difficulty of getting accurate positions was considerable. The fog continuing, it was not till noon on 30th December that the All America’s Cable buoy was found and not until 7 p.m. on the 31st that an attempt to pick it up could be made. In passing it might be remarked that in view of the circumstances far greater risks were taken in boat work on this expedition than is usual on cable repair work. On picking up the A.A.’s buoy it was found to be adrift with only 238 fathoms of cable attached.

Another mark buoy was put down and in the intervals between gales and fog several drives were made to recover the Canso end of Main 4, but without success. On the 8th January the Faraday’s own Cable buoy with the Azores end was found to be adrift. It was picked up in Lat 44° 36’ N. Long 56° 17’ W. The cable had parted. The ship was now at the end of her tether for fuel and had to proceed to Halifax to replenish,

Halifax was reached at 10.30 a.m. on 4th January. In addition to refuelling, 25 miles of heavy core cable and several lengths of picked up cable were discharged to the Commercial Cable Co’s tanks. Also 275 tons of extra ballast was taken in No 3 Cable Tank to give the ship more and much-needed stability.

CS Faraday (2) refuelling at Nova Scotia

Image courtesy of Brian Ellis |

The cable ground was reached again at midnight on the 13th. The John W. Mackay having in the meantime recovered the two ends of the Main 4 and put through, Faraday was instructed to recover the western end of New York and N.F. (1). The depth of water was 2200 fathoms.

Cable was hooked on the first drive but parted at a strain of 18 tons when 570 fathoms from the surface.

The cable hereabouts was found to be deeply buried. Also the nature of the bottom was of a more volcanic appearance. In the shallower water, while working on Mains 4 & 6, the specimens of bottom recovered were of a stiff grey clay nature with a covering of red clay mixed with quantities of red granite and stone. On the NY 1 repair the bottom was almost entirely red and very stiff.

On 17th January cable was again hooked and brought to the bows at a strain of 16 to 18 tons, but when cutting, slipped through the stoppers. Happily no one was hurt, though a man was over the bows at the time.

Over the bow, releasing cable from grapnel to bring inboard

Image courtesy of Brian Ellis |

These tremendous strains were beginning to tell on the grappling rope, wires were constantly snapping, so two 500 fathoms lengths were taken out and new ones put in. Cable was hooked again 8 hours later, but heaving in had hardly commenced when the old rope, which had previously been heavily strained, parted just forward of the picking up gear and the whole 2500 fathoms of rope, grapnel, and cable was lost.

The ship was now short of buoy rope, buoys, lamps and reliable grappling rope. The lamp shortage was relieved to some extent by the arrival of the same on the Lord Kelvin from Halifax with 5 new Venner-Dyke Lamps sent out from London

CS Lord Kelvin delivering mail and supplies to CS Faraday

Image courtesy of Brian Ellis |

The weather was now continually foggy and bitterly cold with snow storms and blizzards, making work impossible. Also with the available grappling rope in doubtful condition, (4 x 5 unused but old stock) it was deemed advisable not to put it to any undue strain.

On the 21st January cable was hooked again and picking up began, but new trouble began too. The rope commenced surging badly round the drum, with one surge a cable hand was injured owing to

being knocked off the coil by a flying bight. Six turns were tried on the drum but still the surging continued under heavy strain. Finding it impossible to bring the cable to the surface, it was decided to buoy the bight on the grapnel and this was done with 1800 fathoms of rope out, the depth being 2200 fathoms.

Another drive was made using some old stock 5 x 4. This had hardly taken the strain of the grapnel when it parted on deck, the end as it went over the side whipping round and smashing the gear face of a bow baulk telegraph, Fortunately again no one was hurt. Another grapnel and 2800 fathoms of rope was lost.

The ship was now practically denuded of any serviceable rope, but a new supply was obtained from the J.W.M. who loaned 2000 fathoms of new 6 x 3. The transfer of rope was effected on 23rd January. With the first drive with the new rope on the 24th, cable was hooked and brought to the bows under a strain of 22 tons. At 11 a.m. the New York end was buoyed. The next day on instructions from N.Y. the end was picked up again, spliced onto the ship’s stock and the remaining 75 miles of the ship’s tanks paid out. The J.W.M. in the meantime had recovered the Eastern End and the two ships between them had sufficient to bridge the gap, this was done. The J.W.M. making the final splice on the morning of 26th January. Orders were received for the Faraday to return to London. The grounds were finally left at 11 a.m. on 28th January.

On the homeward voyage conditions were even worse than on the outward. Field ice was encountered on the night of the 29th when the ship ground and crushed her way through it for 3 hours. Then came a wild run before a succession of westerly gales of hurricane force and mountainous following seas. This put the final seal on the question of the Faraday’s sea-worthiness, Though heavy water was shipped in which an accommodation ladder was washed away and several spars and rails broken. She came through the ordeal splendidly and at a time when more than 50 were hove to. Gravesend was reached on the 6th and the ship docked next morning in the West India Docks having been away 74 days.

Alexander Murdoch sailed again on CS Faraday (2) on the 1935 expedition to lay a telephone cable across the Bass Strait between the Australian mainland and Tasmania. This photograph shows the Faraday’s officers and staff during that expedition; Murdoch is seated in the centre of the front row and is identified by name. He would have been 21 years old at the time. This newspaper report has some further details.

CS Faraday (2): Bass Strait 1935 Expedition |

Alexander Murdoch must have though that a voyage to Australia in the middle of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer would be easy sailing compared to the North Atlantic in the winter of 1929, but newspaper reports of the time show that Faraday again encountered some rough weather in November 1935. The ship was again captained by Murdoch's uncle, Robert Allan, who had been Master of the Faraday since shortly after her launch in 1924.

TWO CABLE SHIPS IN HEAVY WEATHER

Faraday and Recorder Delayed

While the Siemens Brothers’ cable steamer Faraday, which is laying the telephone cable across Bass Strait, has been sheltering from a fierce south-westerly gale at King Island, another cable steamer, the Recorder, has also been experiencing bad weather. The Recorder, which la the cable repair ship of the Eastern Extension Telegraph Co. Ltd., and the only vessel of its type permanently stationed in Australasian waters, reached Williamstown yesterday with 250 miles of different types of submarine cable, which she will transfer to the Faraday. In exchange she will take from the Faraday 24 miles of cable, to be kept in stock for making repairs to the Bass Strait cable and other submarine cables off the Australian coast.

The Recorder is stationed at Auckland Island (N.Z) and several weeks ago she was sent to find and repair a fault in No. 2 telegraphic cable, which runs beneath the Tasman Sea between Auckland and Sydney. For 14 days officers of the ship tried to make repairs, but the weather was very bad, and the work had to be postponed before the Recorder had found the cable in 3,000 fathoms of water. When she was travelling to Melbourne the Recorder met boisterous weather off the coast of New South Wales.

When the Recorder berthed yesterday the Faraday was not waiting for her as had been arranged, for the Faraday has encountered bad weather conditions since she began the work of laying the Bass Strait cable, and has been delayed. It is expected that the Faraday will complete her task this week and will then return to Melbourne.

[The Argus Wednesday 20 November 1935]

Murdoch himself is mentioned in another story about the gale, after he volunteered to swim through the surf to take a line ashore from a small boat, an offer which his uncle declined:

Mr. A.J. Murdock, aged 23, cadet, a nephew of the commander of the Faraday (Captain R. Allan), who was coxswain of the launch, then semaphored the Faraday and asked permission to attempt to swim through the surf with the line. Captain Allan signalled in reply: “Absolutely forbid such an attempt. Human life is too valuable.”

Undeterred, Murdoch was again out in a small boat a week later at the King Island landing point:

The arduous task of landing the King Island shore end was completed at the week-end despite bad conditions and very heavy surf. The commander of the Faraday (Captain R. Allan) decided to risk the surf on Saturday afternoon and the cutter and dinghy were sent away from the ship laden with delicate gear and hauling ropes with which to drag the cable ashore to the repeater station The dinghy with the wireless operator (Mr. F.G. Goodall), the assistant purser (Mr. S. Hesse) and a cadet (Mr. A.P. Murdock), was overturned in the heavy surf but Goodall, with great presence of mind, managed to save the valuable radio transmitter which is used by the shore party to keep in touch with the ship. The three occupants managed to swim ashore.

Despite the continuing bad conditions, the cable was succesfully completed before the end of November, although Captain Allan made his opinion of the local weather quite clear to the Tasmania Advocate in a story published on 29 November:

A distinctly unpleasant impression of the Bass Strait weather will be taken with him from Australia by Captain R. Allan, commander of the cable ship Faraday, which returned to Melbourne to-day, after having completed the biggest submarine telephone cable job in the world—that of laying 200 miles of cable between Tasmania and the mainland.

“It was a rotten job,” said Captain Allan, when the Faraday berthed at Nelson Pier, Williamstown, to-day. “It should have been finished in a fortnight, but it took us a full month instead all because of your foul weather. We had the weather against us practically all the way from the time we started at Apollo Bay until we completed the link at Stanley.”

The Bass Strait cable was opened for service on 25 March 1936. At 161 miles it was the longest telephone cable in the world at the time.

During December the Faraday laid a replacement cable between Cottesloe (Perth) and Rottnest Island in Western Australia. The ship presumably then returned to Melbourne, as Katherine has a greetings card from her father with the message:

HEARTY GREETINGS

AND GOOD CHEER

FOR CHRISTMAS

AND NEW YEAR

From

C.S. "FARADAY",

BASS STRAIT EXPEDITION

Melbourne, Christmas, 1935

The card is signed by officers and staff of the ship; these may be the same men as in the photograph above. The signature just below the photo of the ship is “Robt. Allan, Cmdr.”, the Faraday’s master and Alexander Murdoch’s uncle.

Another signature is that of Hugh Campbell, the Faraday’s Chief Officer, whose story is told here. Campbell also sent a card home.

An Australian newspaper story of 17 January 1936 reported that the Faraday had been called to repair a cable between Zanzibar and Durban, but the ship’s master had no technical information on the cable. The problem was resolved by sending images of the documents over the Beam Wireless Picturegram service to Melbourne, where they were handed to the captain. The ship had left for Durban on 28 December 1935.

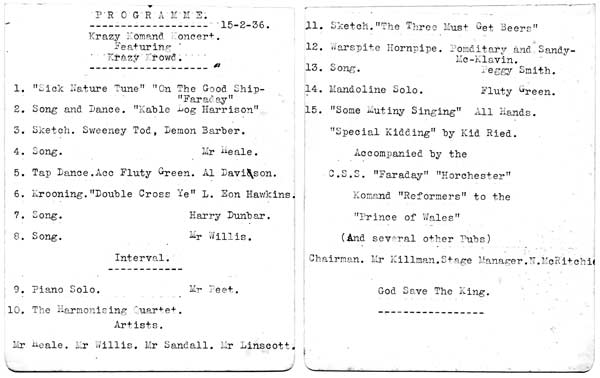

On 15 February 1936 a concert was held on the ship, a common practice to keep the crew occupied during slack times of a cable expedition. Alexander Murdoch’s copy of the programme, perhaps typed by him, is shown here:

“Krazy Komand Koncert Featuring Krazy Krowd” |

Katherine Swinney has no further records of Alexander Murdoch’s service in the cable industry, and it seems likely that he left the sea soon after this, returning to Ireland to take care of family matters.

At the beginning of a cable delivery expedition in March 1941, CS Faraday (2) was bombed and strafed by a German aircraft and the crew abandoned ship. She foundered off Pembrokeshire, where the wreck still lies today. |