| |

According to the Souvenir Book of the 1926 cable chess match, shown below, cable chess matches between Great Britain & Ireland and the United States of America were held every year from 1896 until 1911, when Britain, having won three matches in succession, took permanent possession of the trophy.

A cable chess match was played in 1897 between the House of Commons, London, and the House of Representatives, Washington, the signals being carried by the Anglo American Telegraph Company and the Western Union Telegraph Company. A souvenir chess piece in the form of a rook or castle, engraved with the details of the match, was issued by Telcon, the cable manufacturing and laying contractors for Anglo American.

In 1898 a match between the British Chess Club and the Brooklyn Chess Club was played over the cable of the Commercial Cable Company, and souvenir chess pieces in the form of a knight with a piece of cable mounted in the body were created by Siemens Brothers of London, the cable's manufacturer.

There were also two series of Anglo-American University matches between teams from Oxford and Cambridge and Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia. The first series took place between 1899 and 1903 and was ended by the Russo-Japanese war, which made arrangements for the cabling too difficult. A second series of University matches was held from 1906 to 1910.

In 1924 the opening of the direct Western Union cable between London and Chicago prompted the arrangement of a match between the London Chess League and a team from Chicago. The text and photographs from the Souvenir Book of this event, which was held on November 26th, 1926, are shown below.

For more information on the history of Cable Chess, see Bill Wall's web page. Tim Harding's book Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland, 1824-1987, reviewed below, also has a chapter on telegraphic and cable chess.

|

| |

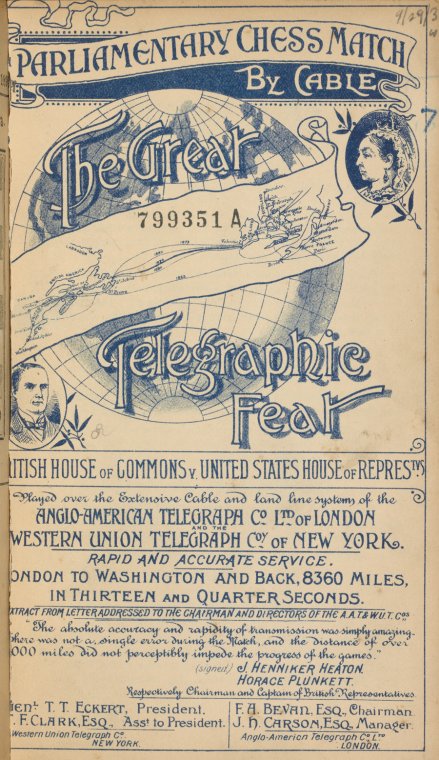

According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle for 30 May 1897: "Three Democrats, a Republican and a Populist" were selected to "defend American chess prestige" in a match between the U.S. House of Representatives in Washington, DC, and the British House of Commons in London. The match was arranged by John Henniker Heaton, a British Conservative MP, and U.S. Representative Richmond Pearson of North Carolina.

The two-day match was carried over the cables of the Anglo American Telegraph Company and

the Western Union Telegraph Company, and took place on May 31st and June 1st, 1897. The result was a draw, 2.5 to 2.5.

To commemorate the event, this souvenir rook (or castle) was made by the brothers Carlo and Alphonso Guilianio, sons of Carlo Guiliano (1832-1895), the celebrated Italian jeweller of the Victorian era.

The elder Guiliano moved to London in 1860 and set up his own workshop in 1861. In 1874 he established an elegant retail business, where he was patronised by Queen Victoria. By the time the chess piece shown here was made, Guiliano's sons, Carlo Joseph (b.1860) and Arthur Alphonse (b.1864) had taken control of the business, which continued to trade until 1914.

As several examples of this piece are known, it seems likely that one was presented to each participant as a memento of the match.

Three views of the chess piece, showing the complete engraved message. The piece is 3" high by 2" diameter at the base. |

The chess piece is engraved:

Chess Match by Cable

Between

House of Commons, London,

and

House of Representatives, Washington

Played Over the Lines of the

Anglo American Telegraph Co. London

and

Western Union Telegraph Co. New York

1897

Contractors

The Telegraph Construction and

Maintenance Co. London

1897

Parliamentary Chess Match by Cable

The Great Telegraphic Feat

British House of Commons

v.

United States House of Represtvs.

Played over the Extensive Cable and land line systems of the

Anglo-American Telegraph Co. Ltd. of London

and the

Western Union Telegraph Coy. of New York

Image courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery |

An article describing this cable chess match as well as another one that same year was also published in the British magazine The Leisure Hour in 1897:

Chess by Telegraph

Nowadays it is not necessary to bring the players face to face, and matches can be played between teams who may be hundreds of miles apart. Indeed, a cable match between the United Kingdom and the United States is now one of our annual fixtures. Sir George Newnes having given a valuable silver cup to be competed for year by year. The last of these matches was played on February 12 and 13, 1897, the English representatives being Messrs. Blackburne, Locock, Atkins, Lawrence, Mills, Bellingham, Blake, Jackson, Cole and Jacobs. The United States team included the young champion Pillsbury, Showalter, Delmar and seven others whose reputation is better known on the other side of the Atlantic.

The play lasted for two days; everything proceeded without a hitch, and in the end the British team won by 5½ to 4½. This result was eminently satisfactory, for the team was almost entirely composed of amateurs, and the selection had been subjected to much sharp criticism.

The process of conducting such a match is a very simple one. A wire connected with the cable is brought direct into the room where the players are seated. Each player declares his move as he makes it on his board, and this move is forthwith "flashed across the sea" and is made known to the opposing player, on whose board a corresponding move is made. This process goes on until all the games are finished and the match completed. Of course the moves are not sent at length, but a most ingenious code is used, by which in fact several moves can be communicated simultaneously. So rapid is the transmission of the moves that, on one occasion during the late match, not more than fifty-five seconds were necessary for cabling a move and its reply.

A similar match was played on May 31 and June 1, 1897, between five members of the British House of Commons playing in London, and a similar number of members of the U.S.A. House of Assembly playing in Washington, the result being a draw of 2½ each. In this match a record of time in cable matches was established, twenty moves being cabled in twenty-one and a half minutes, one move going to and from Washington in forty seconds.

|

| |

Cable chess was still popular in 1926, and this souvenir booklet was published on the occasion of the “First Inter-City Chess Match

by Atlantic Cable between London and Chicago”.

The text and illustrations from the booklet are reproduced below.

|

|

CABLE

CHESS MATCH

SOUVENIR

Edited by W. H. Watts

Prepared on the occasion of the First Inter-City Chess Match

by Atlantic Cable between London and Chicago

NOVEMBER 6th, 1926,

AT

Spring Gardens Galleries, London,

AND

Hamilton Club, Chicago.

Printed and Published on behalf of

The London Chess League

by

PRINTING-CRAFT, LTD.

34, Red Lion Square, London, W.C.,

and Mansfield, Notts.

|

|

The Opening Move

The story

of the inception of the present match is perhaps best told from the American

point of view, and we therefore include a contribution sent to us from

Chicago. This tells the whole story in inimitable style:

In March,

1924, the Western Union Telegraph Company opened the first direct cable

between the cities of London and Chicago. Messages of congratulation were

at that time exchanged between the Lord Mayor of London and the Mayor

of Chicago, and hopes were expressed by these gentlemen that the Ancient

Capital of the Eastern Hemisphere and the Modern Metropolis of the Middle

West of America would, as a result of this direct line of communication,

become better acquainted, and thus increase the feeling of friendly good

fellowship which for fifty years has existed between Londoners and Chicagoans.

It was

shortly after the above incident that a Chicago Scotsman, named John G.

Moncrieff, brought forward the suggestion of an Inter-City chess match,

to be played between teams representing London and Chicago, the moves

to be transmitted across the Atlantic by means of the Western Union direct

cable. There were many difficulties to be overcome before such a match

could be possible. First of all there was the question of “cost.”

A number of Anglo-American wellwishers were written to on the subject

of a guarantee fund and eventually Master-in-Chancery Edwin A. Munger,

Mr. Samuel Insull and Mr. Ernest Reckitt were induced to become the first

guarantors. With those three names as a nucleus Mr. Moncrieff approached

Mr. Maurice S. Kuhns, Chairman of the Chess Circle of the Hamilton Club

of Chicago; this was indeed a Circle move,” as Mr. Kuhns immediately

entered into the project with great enthusiasm, and in the course of a

few days brought the guarantee fund up to 1,000 dollars.

Having

arranged the question of cost, the next move was to send a challenge to

the London Chess League; this was done by the Chess Circle of the Hamilton

Club, as follows:

The Chess

players of Chicago, Ill., U.S.A. challenge the Chess players of London,

England, to a match of six games. The conditions covering the match are

to be as follows:

1. The

players shall be players of Chicago, Ill., U.S.A., and players of London,

England.

2. The

match is to be played under the auspices and direction of the Hamilton

Club of Chicago, who agree to pay the cable charges for the messages from

Chicago to London and from London to Chicago, the said messages to be

confined to the necessary moves of the players.

3. The

match is to be played on Saturday, beginning at 9 o'clock a.m. Central

Standard time of America (3 o'clock p.m. London, England, time), and

to continue until 6 o'clock p.m. Central Standard time of America (12

o'clock midnight London, England) unless completed before that time.

4. Games

unfinished at 6 o'clock p.m. Central Standard time of America (12 o'clock

midnight London, England) to be adjudicated by referees to be agreed upon.

5. The

games in Chicago are to be played at the Hamilton Club of Chicago and

in London, England, at a place to be determined by the interested parties

in London.

This challenge

was promptly accepted by Mr. G. R. Hardcastle, the Hon. Secretary of the

London Chess League.

Mr. Maurice

S. Kuhns is not only a chess match organizer and a chess player, he is

also a chess thinker; recently he perfected a new cable code applicable

to chess matches such as this one. This code was submitted to Senor Jose

Capablanca, Dr. Emanuel Lasker, a number of other prominent chess players

and The London Chess League, who, having tried it out very carefully,

came to the conclusion that it was a distinct advance on anything of the

kind which had hitherto been used for cable chess matches. As a result,

the Kuhns Cable Chess Code has been adopted as the one to be used on the

auspicious occasion of the first London-Chicago Inter-city match.

How the Moves will

be sent

The unique

feature of this match is the transmission of the moves by the Trans-Ocean

Cable, consequently some description of the cable arrangements are opportune.

In order

to become acquainted with these arrangements I made several interesting

visits to The Western Union Telegraph Co.'s London Offices, and had the

whole process thoroughly and carefully explained to me. Messages were

sent and received in exactly the way moves will be sent and received during

the match. Now that I understand, or think I understand, the transmission

of the moves has lost its mystery. As it is impossible for us all to have

the advantage of visits to Great Winchester Street, the following brief

explanation and appreciation must suffice, and so that it may be the more

clearly understood the story is told as simply as possible. For this purpose

we will construct the scene in advance as visitors to the match will,

see it.

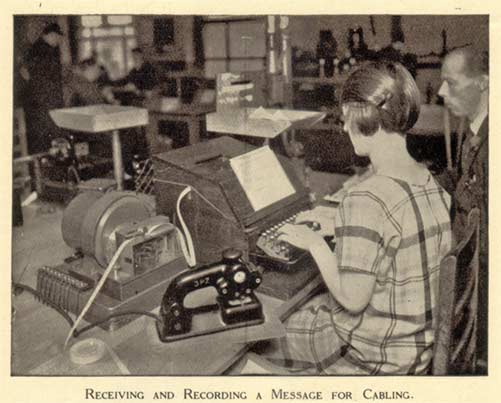

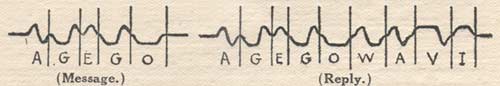

Play in

the Cable Match is in progress. A player at last makes his move, and his

attendant records it in code, ready for despatch to his opponent in Chicago.

This form is handed to one of the special transmitting telephonists in

attendance throughout the match. She is in uninterrupted connection with

Western Union House, for a number of private wires have been installed

for the match. At Western Union House the code message is received by

an expert reception telephonist, and handed by her to the cable operator,

who instantaneously transmits it to the Chicago Office of The Western

Union Co. Then it is transmitted over a private wire to the actual room

in the Hamilton Club in which are the American Players.

The operator is using a tape punch

to create the cable tape from

the original message. The tape is then fed directly

to the cable transmitter on the left which sends the

message out over the cable at a constant speed.

Detail of equipment |

This has

taken a long time to write—and some minutes to read—it may seem a

little complicated, but in actual fact one minute, or less, after the

English Player has made his move it is recorded on his opponent's board

in Chicago.

Those who

understand the working of chess clocks will see that the whole of the

time lost in cabling and telephoning during the course of the game will

be shown by the difference between the combined totals of the times shown

on the English player's own clock here in London, and the American player's

time as shown on his own clock in America deducted from the total time

the game has been in progress. Thus, if No. 1 Englishman's clock shows

3 hours 55 minutes, and No. 1 American's clock shows 3 hours 20 minutes

(total 7; hours), and play has been in progress 7 hours 25 minutes the

total time lost in telephoning and cabling on this game would be but 10

minutes. As the game must be over 60 moves in this time (which means 120

transmissions) the loss amounts to about 5 seconds per move, or 10 seconds

per move and reply. In addition the American's clock in England will show

his time, plus the total cable time, and the English player's clock in

America will show his time, plus the total cabling loss.

A special

code for the ready transmission of the moves has been invented by Mr.

Maurice S. Kuhns, of Chicago, and this code has received everyone's approval.

In this code the last move received is repeated and the new move added.

The initial letter indicating the Board number. The first two cables on

Board 1 may be as follows:

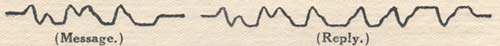

AGEGO, and the reply to this may be AGEGOWAVI.

This means

that on Board A—or Board 1, we move P-Q4, and the reply means: On Board

A. We confirm your move of P-Q4 and reply Kt-KB3.

The two

strips of cable slip recording these moves look like this before translation:

A strip

of Cable Slip as it comes from the machine |

The same

strip translated into the special Chess Code to be used in this

match. Decoded this message means—Board A:- P-Q4, and the reply

—Board A. Confirm P-Q4, reply Kt-KB3.

The upright lines are given to indicate the actual letters as shown

underneath. |

A few facts

regarding the Western Union Telegraph Co.'s organisation and service which

renders such a match possible must be of interest to us, quite apart from

chess. Either in business or in private life we occasionally require their

services, and some of us very frequently. Bankers, Stock Exchange men,

Merchants, Pressmen, Public Officials, Politicians, and many others are

using the Cables all day long, and to them a delay of minutes is of the

utmost seriousness. These men have private telephone or telegraph wires

installed between their Offices and the Western Union Office which enable

them to get just as quick a service as we are getting for this match.

This means that a man sitting in his London Office can decide at 2 p.m.

to cable to his New York Office, and before 2.5 p.m. it is possible for

him to be in possession of their reply—provided there is a private telephone

wire at each end.

Let us

trace a message through again. It may be handed in over the counter, it

may come from a Post Office, or other receiving office, it may come by

ordinary telephone, or over one of the private wires. Suppose it is this

last case. As the telephone operator receives it she types it on a noiseless

typewriter—with over twenty of these working full speed in a small room,

you can't hear a single tap, and there is no screaming on the telephone,

in fact little more than a whisper! The room itself is specially designed

with every acoustic device modern science has achieved, wall, ceiling,

and floor having special coverings to deaden all extraneous sounds. Immediately

typed, the message is handed to the cable operator, who transmits it to

America direct. A matter of seconds after his finger touches the first

key of his machine the reception machine in New York records his first

signal.

At the

present time the message is received by cable recorder and the operator

transcribes, and types it into ordinary characters direct on to the Western

Union Company's familiar form, and it is then either re-forwarded by private

wire, relayed by phone, or sent out by messenger to the person for whom

the message is intended. Shortly there will come into full service a new

automatic “printer” which types the message as received in our

ordinary arabic characters, thus dispensing with the human element in

transcribing from cable signals.

These cable

transmitting and receiving machines are very similar to typewriters, except

that they record on long narrow strips of gummed paper instead of on sheets.

To the right of the typewriter is a

siphon recorder, which

receives

the incoming signal from the cable

and prints the

paper “slip”

containing the coded characters.

The operator is translating from the tape and typing the message

Detail of equipment |

|

Cabling

is thus practically instantaneous. Race results are known in America as

soon as they are known on the course. Election results and news items

are distributed in America at the same moment as they are distributed

here. So efficient is the service that an average transmission time of

two minutes is given daily on all messages filed at the preferred rate.

I walked

into a big London Post Office 20 minutes before closing time, and handed

in a telegram to Bedford. “Will it be delivered to-night?” I

asked. “It will reach Bedford tonight, but it may not get through

until the morning,” was the reply. We all know to our cost how long

it takes inland telegrams to get through, and are inclined to judge cables

proportionately to the distance they have to go.

Bedford

is fifty miles away, and the telegram takes, say, half-an-hour, so to

America should take about 24 hours. Not much hope to finish a game of

chess in twelve hours' play at that rate!

If we complain

about delay on a telegram, three weeks later we receive a printed postcard

to say that our communication has been received and will have attention.

This is an end of the matter, and it is all the satisfaction we get. In

a Cable Service such cavalier treatment would be fatal and any complaint

of delay on a Cable message is thoroughly and promptly investigated by

the Western Union.

Who was

the first genius to think of and suggest Trans-Ocean Telegraph Cables?

It is certain

that Cyrus Field was the first man actually to connect America with Ireland

by a submerged wire in 1858.

Every schoolboy

has heard of “The Great Eastern,” styled the largest ship ever

built, “so large that cargoes sufficiently big to load it could never

be found,” so large that in the end its owners had it broken up,

although many larger ships have been built since. The Great Eastern was

employed to lay the first of the present Trans-Atlantic Cables.

The story

of “The Great Eastern” reminds one of the old G.P.O. on the

eastern side of St. Martin's-le-Grand, and now pulled down. This was expected

at the time it was erected to be “large enough to accommodate all

the correspondence of the whole world for all time,” but, like the

Trans-Ocean cables, the business increased with the increased facilities.

The first

cable was laid in 1858, and lasted two months, and the new one to take

its place was completed in 1866, and a second one completed later the

same year. It was thought at the time that the second cable would only

be required in an emergency, or in case of a breakdown. What would Cyrus

Field and John Pender, its promoters, think of the nine cables operated

by The Western Union at the present time, or to direct through communication

to Chicago and other Western cities, even to San Francisco? The new cable

of the Western Union has a capacity equal to five of the Company's present

cables, and it will be seen that the Western Union are providing for a

vast increase of business.

Between

the laying of the very first cable and that of cables of a few years ago

very little advance had been found possible in actual cable construction,

but this new one embodies really radical changes, and its success has

exceeded the modest claims previously made for it. Most of the advances

made in cabling efficiency during 60 years of public service have been

confined to the very delicate transmitting and receiving instruments,

the result of the late Lord Kelvin's investigations, experiments and inventions.

The possibility

of a breakdown is much more feared by the layman than by those with a

complete knowledge of cabling, and a most interesting story could be written

of cable laying and cable repairing, of the special rights possessed by

vessels engaged on cable work, and of the cables themselves, but these

subjects are outside the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that

by means of certain very delicate instruments it is possible to locate

within a very short distance any breakdown, and to instruct a cable ship

where to go to effect an immediate repair. With their multiplicity of

cables a breakdown of one of the Western Union links during the match

would not present any difficulty.

The uninitiated

look upon the present chess match as a vast and difficult undertaking,

but the Western Union staff are not dismayed; they seem to take it in

their stride. It presents no more difficulties to them than do our daily

tasks to us. What chess players they would make!

|

| |

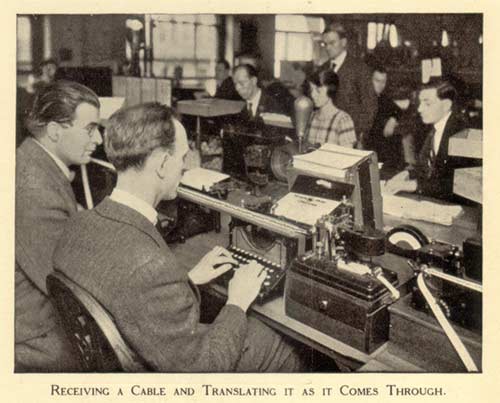

Chess games were played by correspondence for about 160 years, the first formal match taking place in 1824 between Edinburgh and London. Tim Harding, a Senior International Master of correspondence chess, has written the first book to cover the entire history of correspondence chess, from its beginnings in 1824 using the mails up until postal chess was largely superseded by computer communications in the 1980s.

While the book is primarily aimed at chess players with an interest in the history of their game, it also provides much useful information to historians. For the chess enthusiast there are listings of clubs and matches, details of important games, and tables of results. For the historian or general reader, the book gives an insight into the social and cultural climate of each era, presents brief biographies of key players and touches on their rivalries, and shows in each period how new technologies were adopted.

The first revolution came with the Penny Post, introduced in Britain in 1840. This greatly reduced the cost of postal chess, and the mails remained the primary means of conducting matches for the next 140 years. Of more interest to readers of this site, however, is the use of telegraphy, both landline and cable, to exchange moves, to which Harding devotes a chapter.

Just a few months after Morse's telegraph connected Baltimore and Washington in 1844, a short series of chess games was played between the two cities. Morse, however, thought this was too frivolous a use of the telegraph, and put an end to the exchange of chess moves over his wires. Meanwhile, in April 1845 in Britain, the famous player Howard Staunton conducted an experimental match by telegraph over Cooke and Wheatstone's circuit from London to Gosport, near Portsmouth.

1845 experimental telegraph chess match |

Other telegraph matches followed, mostly between clubs in different parts of Britain, and in 1861 the first match was played by submarine cable, between Liverpool and Dublin. Further Irish matches by cable were played over the next few years, but attempts to arrange games between London and Paris were never successful. The first intercontinental match by cable is reported to have been between Liverpool and Calcutta in 1880. And as noted above on this page, matches were played between Britain and the USA beginning in 1885 and continuing until at least the late 1920s.

The telephone was also used for chess, the first game in Britain being in 1878, and chess by radio and fax followed as those technologies became available. The major change, though, was in the early 1980s, when email quietly started to take over. Although accessible initially to only a small number of players, the use of email soon became widespread, and while it is beyond the scope of Harding's book, this eventually led to the present-day boom in internet chess, played by chess enthusiasts worldwide using web chess servers at any time of the day or night.

Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland, 1824-1987 by Tim Harding. 439 pages, softcover. 53 photos, tables, appendices, notes, bibliography, indexes. Published February 2011 by McFarland. |