|

| April 24, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

The Submarine Telegraph

The Niagara had been most

heartily welcomed back to Plymouth, and a cloud of invitations fell upon

her officers. The cable was being put into her with all dispatch. The

Agamemnon and two other war vessels were all ready to co-operate with

the Niagara in the grand undertaking.

|

| May 1, 1858

The Combined Flag of the United States

and Great Britain

Symbolic flag presented to

the U.S.S. Niagara by the

Telegraph Company, to be

used while laying the cable

|

A correspondent, attached

to the Niagara, has furnished us with a sketch of the flag presented by

the Inter-Oceanic Telegraph Company to the officers of the ship, which

will be displayed while the process of laying the cable is in operation.

The company presented a similar flag to the Agamemnon. If the enterprise

is successful, these flags will in all future time possess an historic

interest that never before was associated with the national emblems of

any nation. We have those of Saratoga, of Austerlitz and of Waterloo,

but these speak of warlike triumphs, of the shedding of blood, of the

desolation of peoples; but the flags of the Niagara and Agamemnon we hope

will proclaim a civil triumph - the consummation of the scientific miracle

of the age.

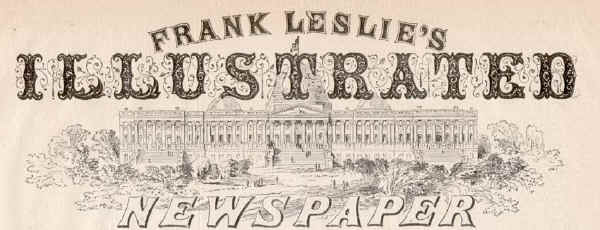

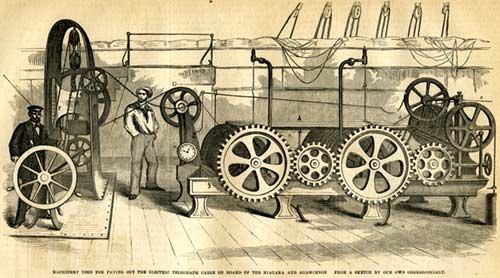

Machinery of the

Niagara

Machinery on the U.S.S. Niagara,

provided for the second attempt

to lay the Inter-Oceanic cable

|

We are also able to give

our numerous readers a correct drawing of the machinery provided for paying

off the cable. It differs from that first used in many particulars, and

more especially in the addition of a gallery or platform along the sides,

for the purpose of affording the engineers entire control of the cable

as it "runs out." The iron network underneath is to prevent

the cable from getting foul of the propeller. By examination of the drawing,

it will be seen that the telegraphic wire as it pays out passes over the

poop and through the grooved wheel, the outer edge of which is covered

by a shell, which keeps it from slipping out of the groove.

|

| May 15, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

The Atlantic Telegraph

This noble work was going

on bravely, and the experiments with the new paying-out machinery were

giving great satisfaction. It had not, however, been decided when the

ships would commence to put the cable down, although, we believe, it had

been determined to commence midway - the Niagara proceeding towards Ireland

with her half, and the Agamemnon coming to America with hers. It is a

pity New York is not the terminus on our side the water, merely for the

sake of the glorious reception the British vessel would have!

|

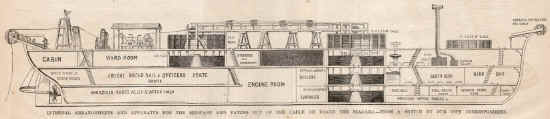

| May 29, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

The Atlantic Cable

All the wire of the Atlantic

telegraph has been removed from the tanks at Keyham excepting about 200

miles, which are in the course of removal, at the rate of about two miles

per hour, to the Niagara. Up to nine o'clock of the 1st of May she had

received 1,070 miles, viz: wardroom coil, 312; hold, 338; lower deck,

170, and main deck, 250. The last named will receive from 30 to 40 more;

the after-tank, on deck, 200 miles, and a second deck forward, 150 miles.

The balance of the wire is daily expected from the manufactory by the

Adonis and another steamship. The total length shipped last year was 1,255

miles; this year the Niagara will take 1,468. Across the after-tank there

is a stage, on which is fitted, right over the cone in the centre, a horizontal

flanged wheel, with the spindle fore and aft; from this wheel the wire

runs once around a vertical revolving barrel, and is then guided by a

horizontal roller to the paying machine over the stern. This coil will

be discharged first, and will be followed by the main deck coil, then

the lower deck and hold, and finally the wardroom. The Agamemnon has received

all her portion of the wire from Keyham, and, like the Niagara, is expecting

some from the Adonis. She has in her upper deck 233 miles; orlop, 95;

and main hold, 932. Here, then, is space for 210 additional miles, which

will complete her lading to 1,470 miles, about the same quantity as that

on board the frigate, and, like her, 200 miles more than last year. The

measurement is by statute miles.

|

| June 5, 1858

Foreign News: England:

The Africa brings news

from the Old World to the 15th. Professor Hughes' experiments have been

eminently successful in transmitting the electric spark through the whole

extent of the cable. On the 13th Cyrus W. Field called upon the First

Lord of the Admiralty, and asked for a steamer in lieu of the United States

steamer Susquehanna, which was unable to attend the Niagara, owing to

the yellow fever breaking out in her. It was immediately granted.

Atlantic Cable

All the ships of the squadron

will leave Plymouth, as we have previously announced, about the 24th or

25th of this month on their experimental trip, which will occupy from

six to ten days. During this about 100 miles of condemned cable will be

used in ascertaining the efficiency of various buoys, laying down and

under-running the wire, &c., and when all doubts and theories have

been practically solved, the squadron returns to Queenstown, makes its

brief final preparations; and starts for the great attempt about the 10th

of June. Both ships, with the accompanying frigates, make all speed for

the centre of the Atlantic, or rather to the centre of the space to be

traversed by the cable, which is about 32 deg. west of Greenwich. Here

the splice between the two halves will be made without loss of time. There

is 1,500 fathoms water where this join must be made, and both vessels

will remain stationary until the splice has well settled on the bottom,

when the Niagara will at once steer for the New World, and the Agamemnon

will return to the Old. Each will steer as fast to her homeward destination

as is consistent with the safety of the undertaking, so the cable will

be either laid or lost within twelve or fourteen days from starting. The

depths to which the Niagara will have to sink her portion vary quickly

and irregularly from 1,500 to 2,500 fathoms, or from 1 3/4 to about 3

1/2 mile; and this is the case also with the Agamemnon's portion of the

distance. But on the American side the water shoals easily and gradually

towards Newfoundland, whereas, on the British portion of the ocean the

Agamemnon will have to surmount a tremendous ridge, which may be called

the Andes of those vast submarine plains of the Atlantic. It commences

at about 15 deg. west longitude, and in the course of a few miles the

water suddenly shoals from 1,750 fathoms to 550. Up this vast rocky precipice

- almost as steep as the side of Mont Blanc - the cable must be laid with

extreme care. The difficulty once overcome, the way thence to Valentia

becomes comparatively of no account.

|

| June 12, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

Atlantic Telegraph

The contract between the

Atlantic Telegraph Company and the English Government was signed and sealed

by the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury and Directors of the Company

on the 20th. It is for a period of twenty-five years from the time the

cable shall have been successfully laid down. The telegraphic fleet had

all assembled at Plymouth and would sail on an experimental trip in a

few days. It consists of the United States frigate Niagara and the British

steamers Agamemnon, Valorous, Gorgon and Porcupine.

|

| June 26, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

Atlantic Telegraph

On the evening before the

departure of the Electric fleet a grand dinner was given by Captain Steward

of the Impregnable and the British officers, to Captain Hudson of the

Niagara and his officers. The quarter-deck was profusely decorated, and

in the evening brilliantly illuminated. The dinner was excellent, and

the healths of the Queen and President were drunk with great applause.

The next evening this much talked of fleet steamed in line for the south-west

in the following order: Gorgon, Valorous, Agamemnon and Niagara!

|

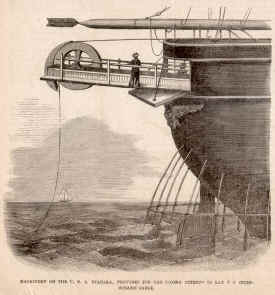

| June 26, 1858

Laying the Telegraph Cable

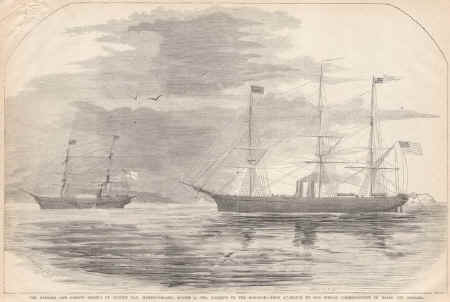

The Niagara and the Agamemnon taking

in

the last of the telegraphic cable in the

Keyham dockyard, Devonport, England

|

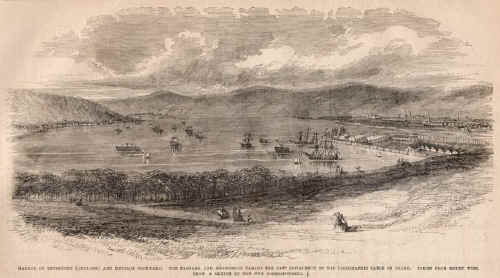

The Atlantic telegraph

squadron, consisting of the Niagara and of three British vessels-of-war,

left the British coast for their important voyage on the 5th of June,

and by the time of our publication the problem of a sub-Atlantic cable

will doubtless have been solved. Our large engraving represents the two

principal vessels as they lay during the month of May in Keyham Dockyard,

affording a fine opportunity for comparing the two magnificent steamers.

The British Agamemnon is of a totally different build from the Niagara,

but is exclusively designed for a ship-of-war, and is capable of little

more than twelve knots an hour under steam; while the Niagara could probably

steam fourteen, but is worthless for warlike purposes. Her great length,

while it gives her velocity, renders her unwieldy to the highest degree.

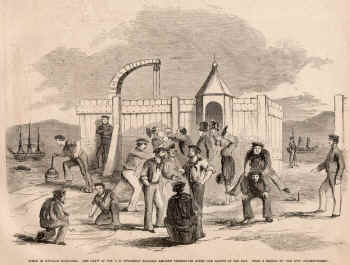

During her stay in Keyham her crew were allowed the use of the dockyard

at night, and our own correspondent forwards us a striking sketch of their

amusements after the labors of the day. The stern red-coated sentry and

the shiny-hatted policeman look on with evident amusement at the varied

sports of their nautical cousins, while an American marine paces up and

down outside, to prevent the unauthorized egress of any of the salts.

A companion sketch represents the Harbor of Devonport and Keyham Dockyard.

Scene in Keyham dockyard, the crew

of the U.S. Steamship Niagara amusing themselves after the labors

of the day, from a sketch by our own correspondent

|

Previously to the final

sailing of the squadron an experimental cruise was made, for the purpose

of testing the new apparatus for the laying of the cable, which resulted

in the most satisfactory success. The vessels were absent during six days,

and in that time paid out several miles of worthless cable (part of that

which was raised from the portion sunk last year) in water three miles

deep, and every imaginable method of splicing, hauling, &c., was fully

tried. Although the cable had been injured in the process of recovery,

and was therefore expected to give much trouble, the machinery was so

admirably contrived that not a "kink" took place, and it may

therefore be reasonably expected that the perfect cable will be laid without

difficulty, provided the vessels are overtaken by no inconvenient gales.

The fortnight succeeding the 5th of June, however, has been ascertained

by the experience of many years to be the calmest of the year, and as

the vessels will commence their operations this time from the middle of

the Atlantic, they will of course be exposed for only about seven days

to dangers from the elements. Having reached a given point in the ocean,

the two ends of the cable will be spliced, when the Niagara will steam

away towards Newfoundland, and the Agamemnon to Valentia Bay on the Irish

coast. If all goes well, we shall shortly be receiving the news from Europe

several hours before the events actually occur, as the electric fluid

will beat the sun by at least five hours in its circuit.

Harbor of Devonport (England) and Keyham

dockyard. The Niagara and Agamemnon taking the last instalment of

the telegraphic cable on board. Taken from Mount Wise. From a sketch

by our own correspondent.

|

|

| July 3, 1858

Atlantic Telegraph Machinery

Machinery used for paying out the electric

telegraph

cable on board of the Niagara and Agamemnon.

From a sketch by our own correpondent.

|

The laying of the great

Telegraph cable has necessitated the invention of new and even complicated

machinery, while at the same time the accidental failure of the first

attempt has brought about changes and improvements in the construction

of the breaks and drums. We engrave, from drawings by our own correspondent,

a complete representation of the machinery used. As is well known, the

principal difficulty in the important undertaking is the even descent

of the wire into the ocean without acquiring such velocity as to be broken

by one of the sudden strains to which it is exposed, or coiling itself

in a "kink." Of course the heavy swell of the Atlantic - and

it must be remembered that even a calm implies a gigantic roll or swell

of the mighty waves - will alternately raise and lower the vessel which

is paying out the cable to such an extent as to necessitate a regulating

power upon the descending wire, and in a gale of wind or on a chopping

sea this necessity is vastly increased.. The machinery introduced for

this purpose is admirably simple, and was contrived by Messrs. Easton

and Amos, of Greenwich, England. It is placed on deck, in the afterpart

of the vessel, and a little way to the right of the mizenmast. The cable,

as it is uncoiled from the hold, passes over a horizontal groove and a

deeply channelled wheel on to the great drums, around which it passes

to another guiding wheel, and thence to the break machinery. These numerous

windings preserve it from kinking, and the breaks are most ingeniously

protected from the dangers of a too sudden jerk. Half between them and

the stern is a grooved wheel, working on a sliding frame which is furnished

with weights fixed on a rod, ending in a piston inside, or cylinder filled

with water. This piston being somewhat less in diameter than the cylinder,

leaves room for the water to circulate around it, although not without

pressure. As, therefore, the cylinder is full, it is obvious that the

play of the piston is impeded by the water, and that it will yield to

pressure only gradually and not to a sudden jerk. It is now necessary

to regulate the tension of the wire, which passes over the groove wheel

and a block or sheaf, overhanging the stern, into the sea. The engineer

weights the slide accordingly, the weight being hung on the shaft of the

groove wheel under which the cable passes, and riding, therefore, on the

cable itself. An index or dynamometer indicates the exact amount of pressure

employed. Under this index is a steering wheel, which is connected with

the weighting shaft, and a steersman, placed at this wheel, studies the

index as he would a binnacle compass. The engineer instructs him as to

the amount of pressure to be exerted, and a turn of the wheel suffices

to relax or increase the strain. The abruptness of this, again, is guarded

against by the water cylinder around the piston.

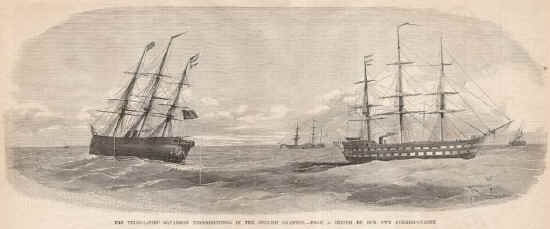

Another sketch by our correspondent

shows the telegraph fleet in mid-ocean.

The telegraphic squadron experimenting

in the English Channel.

From a sketch by our own correspondent.

|

Internal arrangements and apparatus

for the stowage

and paying out of the cable on board the Niagara.

From a sketch by our own correspondent.

|

|

| July 31, 1858

The Atlantic Telegraph

And so the great cable,

on which the hopes of two worlds rested, has broken for the second time!

We trust the next attempt will achieve the grand object, or at all events

approximate nearer to success, for it must be confessed the last has been

a more total failure than the first. The idea that two such nations as

England and America will abandon the undertaking shows a great ignorance

of our national character - since it is not likely a people who for three

centuries continued its researches to discover a North-west Passage, for

a mere theoretical object, will relinquish, after only two failures, one

so practical and important as the instantaneous communication between

Europe and America. We are disposed to think that the people on both sides

the Atlantic will be more inclined to take counsel of the great Bruce,

who, having been seven times defeated in his attempts to regain his crown,

was lying one morning on his couch in despair, when he observed a spider

endeavoring to reach a certain spot in the corner of his room - it failed

- again it essayed, and failed again - thus on till the eighth time -

when it at last succeeded! Bruce rose comported from his bed, and shaking

the despair from his soul, made another attempt for his crown. We all

know that he triumphed! We think with Bruce, that what a spider did man

can do, and that despite the recent mishap, the cable will be eventually

laid.

The details of the disaster

are very contradictory, although we have only the statement of the officers

and engineers of the Niagara, who have somewhat prematurely, and disingenuously,

we think, thrown all the blame on those on board the Agamemnon. We forbear

to point out the manifest discrepancies, as a few days will put all right;

but we do most thoroughly hope the blame really rests where our officers

of the Niagara says it does, otherwise the national character will be

compromised by their statements, should they prove unfounded. In so great

an undertaking, and especially when so much more has been done by the

British Government than by our own, it will, indeed, be a deplorable and

humiliating thing, after the haste made by the staff of the Niagara to

accuse their British associates, should the blame really rest with us

instead of with our partners in the enterprise, since it will naturally

indispose the English Government to admit us to any participation in their

future, and we deliberately add, successful efforts.

|

| August 7, 1858

Gossip of the World: England:

The Atlantic Telegraph

The details of the mishap

have been published, and the failure rests between both vessels. The last,

however, we are glad to know did happen on board the Agamemnon,

although two breaks previously occurred on board the Niagara. It had been

agreed that both ships should return to mid ocean in the event of the

breakage taking place at a hundred miles, and as only one hundred and

eighteen had been paid out by the Agamemnon, the captain decided on going

back to the rendezvous, where she waited eight days. The captain of the

Niagara, however, construed the order literally, and returned to Cork.

They have now once more sailed for mid ocean, to make one more attempt,

as they have two thousand five hundred miles of electric cable yet remaining.

From the fact that the cable broke with a strain of two thousand two hundred

pounds upon it, when it was guaranteed by its makers to bear six thousand

nine hundred, we have little hopes of a successful termination to this

grand enterprise. They were to sail from Cork on the 17th July, the day

the Europa left Liverpool.

|

Front page of August 21, 1858

|

August 21, 1858

The Ocean Telegraph

So striking an instance

of steady resolve and indomitable perseverance, followed, after many failures

and disappointments, by complete success, has seldom been presented, as

in the case of the accomplishment of this wonderful international undertaking.

After years of planning and further years of attempt; after failure and

ridicule; after vast and futile expenditure, and in the midst of generally-anticipated

defeat, two continents have

been penetrated to their remotest extremities by an electric thrill, as

the great achievement was made public in the simple words,

"THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH

CABLE HAS BEEN LAID!"

Since the year 1842, when

Professor Morse first commenced his series of experiments in the laying

of submarine cables, the idea of an Atlantic telegraph has never slumbered.

On the 10th of August, 1843, Professor Morse wrote to the Secretary of

the Treasury:

"The practical inference

to be drawn is, that a telegraph communication may be established across

the Atlantic. Startling as this may now seem, the time will come when

this project will be realized."

At the same period the

idea was put forward in England; but slight hopes were entertained of

its fulfilment until the laying of the Dover and Calais telegraph in 1851.

Next year the line to Ostend was successfully submerged, and further attempts

ensued in rapid succession. By the beginning of 1858, more than thirty

lines of submerged cable existed, varying in length from one to four hundred

miles. When the practicability of submarine telegraphing became undoubted,

the project of throwing an electric wire across the Atlantic was actively

taken up. We believe that the first steps actually taken towards the formation

of a company, with this end in view occurred in New York, where Peter

Cooper, Professor Morse, Moses Taylor, Wilson G. Bunt, Cyrus W. Field

and Marshall O. Roberts associated themselves together for the purpose

of carrying out the enterprise. Their first proceeding was to obtain charters

from the British Colonial Governments, granting monopolies of the line

of telegraph between Newfoundland and the American continent. After various

vexatious interruptions, Newfoundland was put in direct communication

with all parts of the Union, and in 1856 the project for the main line

was brought before the Legislatures of Great Britain and the United States.

Bills were carried in Parliament and in Congress which insured to the

Telegraph Company governmental assistance in laying the wire. The British

Government immediately promised the assistance of national vessels, and

the same boon was consequently obtained from our own. Each Government

agreed to pay seventy thousand dollars annually for the use of the line,

and, in consideration of the additional subsidy on the British Government,

all messages emanating from that source are to have priority over all

others. In case the United States Government guarantee to the company

an equal sum, their messages are to share this precedence with those of

Great Britain. Both termini of the line besides were unavoidably to be

on British territory. The company was located in England, where its management

is to be conducted and where nearly all the stock is held. The number

of shares issued amounted in all to three hundred and fifty, at a par

value of one thousand pounds, upon which six hundred pounds have been

paid per share. The manufacture of the cable was commenced by Messrs.

Glass & Elliot, at Greenwich, England, in 1856, and in the spring

of 1857 the U.S.S. Niagara and H.M.S. Agamemnon commenced taking it on

board. The U.S.S. Susquehanna was also detailed to wait upon the Niagara,

and four British men-of-war completed the squadron. The cable manufactured

was composed of seven copper wires closely connected or twined together,

and protected by an exterior of three coats of gutta percha. Outside this

again were six strands of yarn, and finally an external coating of wire,

making the cable eleven-sixteenths of an inch in diameter. Its flexibility

was so great as to allow of its being tied around the arm without injury,

and its strength such that, if suspended vertically in water, it will

bear six miles of its own length before breaking.

The first attempt was made

by commencing to lay the cable in one stretch from land to land, and the

Niagara, having landed her end at Valentia Bay on the 5th of August, set

sail, two days later, on her errand, attended by the hopes of anxious

nations. It was agreed that the splice should be made in mid-ocean, and

that the Agamemnon should carry her half of the cable towards Newfoundland.

But failure was in store for the expedition. On the 11th of August, while

the Niagara was in two thousand fathom water, a clumsy engineer suddenly

checked the cable while the vessel was rising on a heavy swell, and the

wire parted, no less than four hundred miles being lost. The vessels proceeded

at once to Ireland; and the Niagara, after repairing, returned to the

United States. Nothing discouraged, however, by the failure, the company

immediately caused the manufacture of fresh cable in England, and on the

8th of March, 1858, the Niagara again sailed for Plymouth, where she arrived

on the 23d. The Agamemnon, with other men-of-war, was again detailed by

the British Government for the telegraphic enterprise. During several

months the two huge battle-ships lay peacefully side by side, coiling

in, day after day, the little cable, scarcely two fingers thick, which

was to bind two continents together. The Niagara was commanded, as in

the previous year, by Captain William L. Hudson, who for forty-two years

has untiringly persevered in the service of his country; and the Agamemnon

by Captain George W. Preedy, one of the most gallant and experienced Post

Captains in the British navy. By the end of May the cable was safely coiled

on board the two vessels, and on the 10th of June the squadron sailed

from Plymouth Sound for the rendezvous in mid-ocean. They met with very

heavy weather, but succeeded in making the splice on the 26th of June,

when upwards of forty miles of cable were laid. It parted, however, in

the depths of the sea, and a second attempt, commenced on the 28th, had

no better success. After making the splice the vessels separated, but

the cable parted twice while being paid out from the Niagara, and on the

night of the 29th, as afterwards ascertained, it broke as it was being

submerged from the Agamemnon. The vessels were two hundred and ninety-one

miles asunder, the Agamemnon having paid out one hundred and forty-six

miles, and the Niagara one hundred and forty-five, and both vessels put

back to Queenstown, Ireland, where they arrived in the beginning of July.

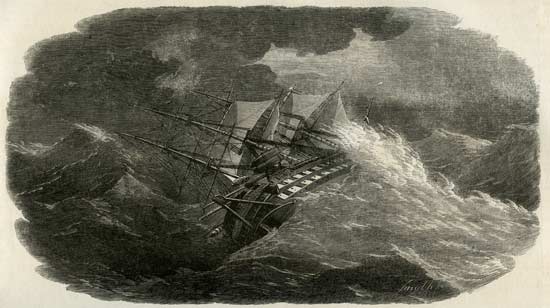

It was in the commencement of this expedition - on the 20th and 21st of

June - that the vessels met with the frightful storm which delayed the

laying of the wire, and compelled the Niagara to separate from the Agamemnon.

The Agamemnon, with the Atlantic cable

on board,

in the great storm on the 20th and 21st of June, 1858

Reproduced by Leslie's from the Illustrated London News,

in turn reproduced from an original drawing by Henry Clifford |

Three several attempts

had now been made, and three decided failures had been the consequence.

Wiseacres shook their heads, and testified that they "had always

expected it; the project was mere moonshine, and success was impossible."

The company did not think so; or, at least, they determined to make one

more trial this year. Each vessel had still eleven hundred miles of cable

on board, and on Saturday, July 17th, the four vessels comprising the

telegraph squadron sailed from Queenstown. On Thursday, the 29th, all

were waiting, in a calm sea, at the rendezvous, latitude 52 deg. 59 N.,

and longitude 32 deg. 27 W., and the splice was effected at one P.M. Then

the two vessels slowly separated, the Agamemnon and Valorous heading for

Ireland, the Niagara and Gorgon for the coast of Newfoundland. Day after

day they steamed onward through the quiet sea, each with its ever lengthening

trail of cable silently dropping to the depths of the Telegraphic Plateau,

and continually exchanging signals through its electric wire. Thus the

occupants of each vessel were kept informed of the safety of the cable.

Meanwhile England and America had settled down into a profound conviction

that the fourth attempt could by no possibility succeed.

On Wednesday, August 4th,

however, the Niagara entered Trinity Bay, and at the same time the Agamemnon

was safely steaming up the Bay of Valentia. The cable was laid! It only

remained to connect the heavy shore end with the main wire, and by the

evening of Thursday the shore end was landed on both sides of the Atlantic.

On Friday signals passed continually from the Valentia to the Trinity

Bay telegraph house.

About noon on Thursday

a brief telegraphic despatch from Newfoundland reached New York and the

other Atlantic cities. It was worded simply, "The Atlantic Telegraph

is laid! The U.S. steam frigate Niagara, Captain Hudson, and British war

steamer Gorgon, Captain Dayman, arrived at Trinity Bay yesterday (August

4th), and the Atlantic cable, the working of which is perfect, is being

landed to-day."

This brief announcement

was discredited by the majority. The public steadily refused to believe

that it could have gone wrong in anticipating a fourth failure for the

enterprise, but more explicit despatches were received on Friday and the

following days. Telegraphic messages passed between Mr. Field, at Trinity

Bay, and the President of the United States, and confirmatory messages

were despatched to the Associated Press. As, however, the electric instruments

were not put up on either side of the Atlantic, the royal message from

Queen Victoria to Mr. Buchanan was delayed, and until its passage no ostensible

communication took place between the two continents.

As the certainty of this

wonderful achievement pervaded the United States and British America,

the utmost enthusiasm was testified by the entire population. Everywhere,

from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Atlantic to

the Mississippi, public rejoicings were held, although formal municipal

demonstrations have been for the most part delayed until the line should

be actually opened.

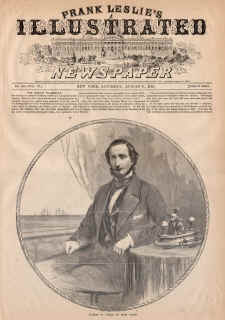

To the energy of Cyrus

W. Field, whose portrait we present upon the first page, a great part

of the success of this wonderful enterprise must be ascribed. As Vice-President

of the Board of Directors he has been indefatigable in pushing forward

the realization of the gigantic scheme. Mr. Field, like Professor Morse,

is a native of New England, the son of a Massachusetts clergyman, and

has been for about twenty-five years in business in New York.

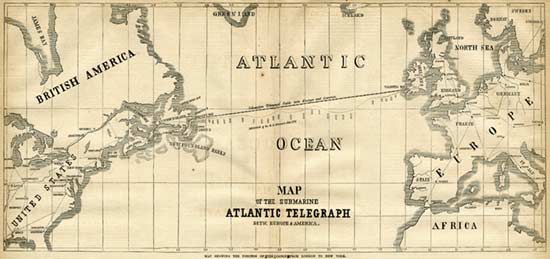

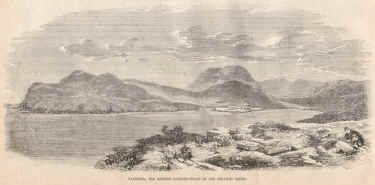

A few words in description

of the plateau and of the termini of the Atlantic telegraph will doubtless

prove acceptable to our readers. The starting point on the Irish coast

is Valentia Bay, in the county Kerry, a wild and romantic indentation

of the coast, a few miles to the south of the celebrated Dingle Bay, and

protected at its entrance by the large island of Valentia. The bay offers

a tolerably safe anchorage to vessels of a large class, but its surroundings

are barren and scantily inhabited. About three miles from the head of

the Bay stands the thriving town of Cahirciveen, a modern-built and pretty

place, situated upon and taking its name from the river Cahir. This district

is popularly known as O'Connell's country, from the fact of its having

been the birthplace and residence of the great agitator. Close by to Cahirciveen

is Cashen the house in which O'Connell was born, and about six miles distant,

stands Derrynane Abbey, where he resided in the plenitude of his fame.

At a little distance from Cahirciveen is Knightstown, near which the telegraph

house is located. The station is situated about four hundred yards from

the beach, at the head of the small cove which terminates the Bay, whence

the wires extend inland to Cork and Dublin, whence they cross over to

England, and thence communicate with all parts of the European continent.

Map showing the position of the cable

from London to New York

|

After much deliberation,

the choice for a cis-Atlantic station of the Atlantic telegraph fell upon

the Bay of Bull's Arm, at the head of Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. This

spot was selected for various reasons. Its situation, open to the eastward,

and directly facing the Irish coast, was a great recommendation, but the

principal advantage consisted in the character of the beach and coast.

It has been found that cables laid in shallow water, upon a rocky bottom,

are liable at any moment to be cut or worn through by chafing against

the rough edge of the stones, and that a sandy or muddy bottom is alone

suitable for telegraphic purposes. This condition was admirably fulfilled

in the character of the Bay of Bull's Arm. Landed here, the telegraph

will be hereafter carried across the narrow peninsula (four miles across)

which separates Trinity from Placentia Bay, and thence will be laid, by

another submarine line, to Halifax, Nova Scotia. This arrangement will

obviate the inconvenience of a land line across Newfoundland, which is

liable to constant interruptions through the storms of winter, and which

it is frequently impossible to repair for days together. It will doubtless

not be long before a submarine line is also laid from Newfoundland to

Portland, Boston, or New York.

At the head of the Bay

of Bull's Arm, about half a mile from high-water line, the telegraph-house

will be erected. This will be a spacious frame building, containing, in

addition to the office or operators' department, a sitting-room, a kitchen,

eight bedrooms, and all the other et ceteras of a well-appointed

household. It is the intention of the company to provide the operators

with a library; and if they do not have enough to interest them in what

they will find in it, in themselves, in the country, and in their business,

they will be hard to please indeed. The force of operators will number

seven, and these must have, among other qualifications, a perfect knowledge

of French, German, Italian and English, so that they may be enabled to

receive and transmit messages in all those languages. In addition to the

operators, there will be five mechanics to repair the telegraph instruments,

and to perform any other work that may be required of them in their particular

trade.

The entrance to Trinity

Bay is about thirty miles wide, and on either side rise the bold headlands

of Baccalo and Horse Chops - the latter of which is about five hundred

and the former seven hundred feet in height. The shore of the bay is marked

by indentations and smaller bays, and inlets have been worn into its rocky

boundaries by the restless action of the sea, which breaks here with resistless

fury. Large caves, running far into the mountain barriers, have been hollowed

out by the same agency, and the deep seams that scar the front of the

rocks show that time has also left its mark upon them. Taken altogether,

there is much to admire in the scenery about Trinity Bay, and in the summer

season it possesses many attractions for the lover of nature, while in

the winter its frozen, desolate look will do much towards developing all

the domestic affections and virtues by teaching the necessity of keeping

in-doors. And this, in justice, in fairness and in truth, is all that

can be said about Trinity Bay.

The "Telegraphic Plateau"

is the name given to an extraordinary bed or bank extending completely

across the Atlantic, which would appear to have been destined by nature

for the purpose to which it has been applied. This bed or plateau appears

to consist in the accumulated washings of the Gulf stream and the Arctic

current, which has contributed, by their adverse action, to build up between

Europe and America this submarine highway. At the greatest depth the lead-line

brings up "bottom" at two thousand and eighty fathoms, or twelve

thousand four hundred and eighty feet, while on each side of the plateau

the bed of the Atlantic shelves off to the frightful depth of twenty-four

thousand feet, or between four and five miles. This plateau is covered

to a considerable depth with minute shells, imperceptible to the naked

eye, some of which have been brought up by the sounding apparatus in a

perfect state, thus proving that the water in those hitherto unfathomed

depths must be perfectly still and motionless; as, were there any motion

or current, the abrasive action would be manifest in its effect upon the

specimens of the bottom raised. When we reflect upon this extraordinary

connecting link between the two foremost stations of the earth, it would

really seem that it must be due to an especial Providence, and that Britain

and America - mother and daughter - have been joined indeed by the marvellous

prevision of the Almighty. The projected message of the Sovereign of England

appears indeed in such a case appropriate; and two worlds may shortly

echo, two mighty nations gratefully repeat: "Whom God hath joined

let no man put asunder!"

|

| August 28, 1858

THE ATLANTIC

TELEGRAPH COMPLETED

Transmission of the Messages of

QUEEN VICTORIA AND PRESIDENT BUCHANAN

Great Rejoicings throughout the United States.

The telegraphic messages of Queen Victoria

and President Buchanan

|

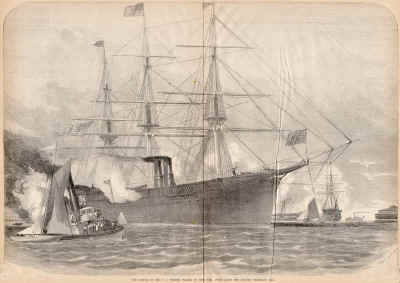

We were enabled in our

last to bring down the account of the successful laying of the Atlantic

telegraph cable to the arrival of the Niagara and Gorgon in Newfoundland,

and the transmission of the great intelligence to every accessible part

of the United States. Since then the crowning success has been attained

by the transmission of Queen Victoria's message to the President of the

United States, and the frigate Niagara has arrived at New York, amid the

acclamations of an entire people, and glorious in the termination of her

peaceful task. We are now able to present illustrations, from the pencil

of our own correspondent, of the arrival of the Niagara and Gorgon in

Trinity Bay, and of the landing of the shore end of the cable, together

with the scenes attendant upon the arrival of the Niagara in New York

harbor.

The Niagara and Gorgon sailing up Trinity

Bay,

Newfoundland, August 4, 1858, icebergs in the distance.

From a sketch by our special correspondent on board the Niagara.

|

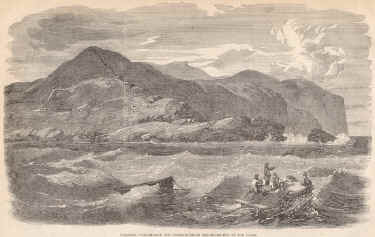

Valentia - catamaran for under-running the shore-end

of the cable

|

Arrival of the Niagara

and Gorgon at Trinity Bay

It was about eight o'clock

on the cloudless morning of August 4 that the cry of - "Land ho!"

rang from the mast head of the Niagara, and the terminus of the Atlantic

telegraph was in sight. A few hours' steam brought the noble vessel to

the entrance of Trinity Bay, where she was received by the British war

steamer Porcupine, especially detailed for telegraphic service. Large

icebergs were seen at a short distance from the land. As the little squadron

approached the coast the British ensign was hoisted by the Niagara, and

the stars and stripes by the Gorgon, the cable being slowly paid out as

the vessels stood in towards the shore. At a little after two A.M., on

the 5th of August, preparations commenced for landing the shore end. The

Niagara's boats were lowered, and received on board about a mile and a

half of heavy cable, which formed the shore end laid last year by the

Niagara in Valentia Bay, and was taken up after it broke on the 11th of

the month. Three hundred miles had been laid from the Niagara in 1857,

a portion of which was recovered by "underrunning" from on board

a stout raft or catamaran, and this operation is illustrated in our engraving

above.

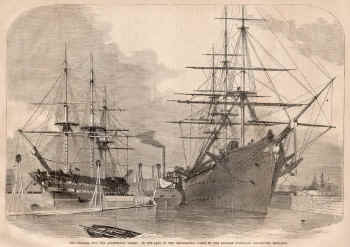

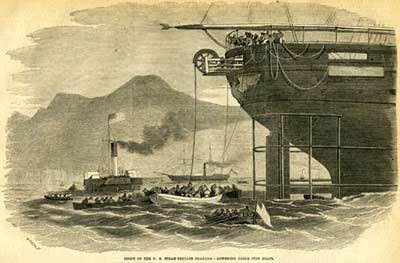

Stern of the U.S. steam frigate Niagara

- lowering cable into boats

|

The Gorgon was anchored

close to the Niagara, and her boats were called away at the same time

with those of the American frigate to assist in laying the shore end.

The two captains, Hudson, of the Niagara, and Dayman, of the Gorgon, who

equally share the credit of the successful voyage, were also in readiness

to land. Captain Dayman, one of the most energetic and able officers in

the British service, was, although completely exhausted by his fatigues,

most active in his supervision of the preparatory movements. For five

out of the six nights of the voyage he took no sleep, but was constantly

on deck, determined personally to see that the course of the vessel, pilot as she was to the Niagara, was

duly kept. Captain Hudson, indeed, asserts that without the Gorgon the

cable could not have been laid, as the compasses on board the Niagara

were so much affected by local magnetic attraction as to be almost useless

for navigation.

Landing of the Cable

Valentia, the eastern landing-place of the Atlantic

cable

|

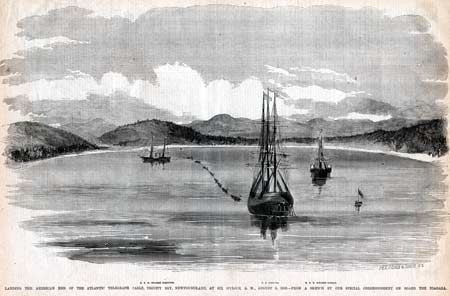

H.B.M. Steamer Porcupine, U.S. Niagara,

H.B.M. Steamer Gorgon.

Landing the American end of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable,

Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, at six o'clock A.M. August 4, 1858.

From a sketch by our special correspondent on board the Niagara.

|

At a little after sunrise

the Niagara's and Gorgon's boats were ranged in line in the romantic Bay

of Bull's Arm. The end of the cable was soon safely brought ashore, when

the three captains, with their officers and men, formed a chain for the

purpose of hauling it inland to the telegraph station, which is situated

about half a mile from the shore. This concluding operation was speedily

accomplished, and the Niagara's share in laying the Atlantic Telegraph

was complete.

The Niagara at New

York

Early in the morning of

August 9th the Niagara and Gorgon left Trinity Bay for St. Johns, where

they arrived the same evening, and whence, after coaling, the Niagara

sailed for New York. Her expected arrival occasioned the most eager enthusiasm

in the metropolis, and for three days before she passed Sandy Hook a continual

lookout was kept. Several false reports of her approach were circulated,

but at length on Tuesday, August 17th, a British steamer arrived, and

announced that she had passed the Niagara within three hundred miles of

the Narrows, and at two P.M. of Wednesday she was descried from the Battery,

where a large assemblage was already in waiting to witness her arrival.

At least twenty thousand persons, it is calculated, were collected upon

and around the Battery. A detachment of the Scott Life Guard, commanded

by Captain Browne, was in readiness, and as the Niagara advanced up the

Bay greeted her with a salute of two hundred guns. As she passed Staten

and Governor's Islands, a welcome was also thundered forth from the batteries,

and the Spanish frigate Berenguela added her salute to the rejoicings.

Most of the vessels in the harbor were dressed in flags, and the steamers

Persia, City of Washington, Daniel Webster, Roanoke, with other vessels,

either fired salutes or lent the shrill scream of their steamwhistles

to the celebration. Several of the river steamers delayed their sailing

in order to give their passengers an opportunity of seeing the magnificent

frigate. At a little before five P.M. she reached the Battery, surrounded

by a throng of steamers, yachts, and boats of every description, where

she dropped anchor to wait a favorable moment for proceeding to the Navy

Yard.

Arrival of the U.S. steamer Niagara at New

York after laying the Atlantic telegraph cable

|

The officers of the vessel

were assembled aft, and repeatedly acknowledged the vociferous compliments

they received from the crowds which surrounded her. About seven o'clock

the anchor was again weighed and the Niagara slowly moved up the East

River towards the Navy Yard. The shipping at the wharves, the piers, buildings,

barges, ferry-boats, and, in short, every imaginable spot which was capable

of affording a foothold, was crowded with spectators. It was dark by the

time the Niagara had reached her moorings, and a number of buildings were

illuminated, while fireworks were continually discharged.

Immediately upon the final

anchorage of the Niagara, Captain Hudson left the vessel and proceeded

to his home in Brooklyn, where he met with an enthusiastic reception.

He was met at the Mansion House, where he has long resided, by Peter Cooper,

Wilson G. Hunt, George Hall, C. W. Field, Edward Fisk, and some other

gentlemen. Ex-Mayor Hall briefly addressed Captain Hudson, who replied

in a pithy, sailor-like speech, and a procession was then formed to escort

Captain Hudson to the City Hall, there to receive the congratulations

of his fellow-citizens.

It was a matter of general

regret that the Niagara did not arrive in time to take part in the general

celebration held on Tuesday, the 17th instant.

|

|

August 28, 1858

Celebration in New

York on Receipt of the Queen's Message.

The news that the Queen's

message had been transmitted to his Excellency the President was circulated

through the city on Monday afternoon, and announced in the hotels, theatres

and other places of public resort. During the night of Monday both despatches

- that of Queen Victoria and the reply of the President - were received

at the publication offices of the various newspapers, in time for insertion

in Tuesday morning's editions, and caused an immense additional sale of

the various sheets. At a little after five the jubilee was ushered in

by the discharge of cannon in the Park, and the booming of the salute

was in some cases the first intimation to strangers, who arrived by steamers

and railroads about that hour, of the safe transmission of the message.

As the sun cleared up the sultry fog which overhung New York at dawn,

his rays fell upon an assemblage of cities - New York, Brooklyn, Williamsburg,

Hoboken, Jersey City - in gala costume. Broadway was gay with the waving

flags of every nation, and the flag of England flaunted at the Battery

side by side with the stars and stripes. Almost without an exception,

the shipping in the harbor were decorated with flags. The church bells

pealed at noon through the entire length and breadth of New York, and

the chimes of Trinity Church rang more merrily than ever before. Wherever

a bell or a steam-whistle was located in factories and shipyards their

noise was added to the almost universal sound. As early as three A.M.

the intelligence of the arrival of the Queen's message reached the Central

Park, and highly delighted the large force of men now at work there. Flags

were hoisted at sunrise, and a salute of one hundred guns fired. One hundred

blasts were also discharged. The workmen, of whom there were nearly two

thousand present, chiefly of Irish origin, sent a deputation to the Superintendent,

asking permission to celebrate the glorious event, and leave was readily

granted them. They held a brief consultation, and in a very short time

had decided on a plan for a procession, in which they were at once joined

by the laborers at work on the New Reservoir, forming an addition of nearly

one thousand to the number. The whole procession, when formed, included

very nearly three thousand individuals, with about one hundred carts and

five hundred horses, all decorated with twigs and branches, and with improvised

banners borne at intervals along the line.

The procession was headed

by a detachment of the Central Park Police, in their full uniform, and

preceded by a brass band. The workmen marched in squads, the majority

shouldering their picks, spades and other tools, while wagons, filled

with implements, were interspersed in the line. The procession was some

two and a half miles long, and excellent order was kept during its long

march. On reaching the City Hall the procession drew itself up in the

Park, and loud outcries were made for Mayor Tiemann, who appeared and

addressed the workmen, as did also Mr. Green, the President of the Board

of Commissioners of the Central Park. The speeches being concluded, the

procession filed out into Chatham street and marched back to their place

of labor.

The streets were crowded

during the entire day with visitors from out of town, who had arrived

to witness the telegraph jubilee, and knots of wondering spectators everywhere

surrounded the preparations made for illumination in the evening. Long

before darkness had descended upon the city-such was the eagerness to

proceed with the celebration-rockets were shooting upwards from a hundred

different localities, and bonfires were brazing all over New York.

Display in the Harbor

The shipping in the harbor

and at the wharves were almost foremost in demonstrations of joy. Foreign

vessels especially, burst out into a gay eruption of bunting, and the

flags of Great Britain and America waved from nearly every mast. As might

naturally be expected, the great ocean steamers, of which there were an

unusual number in port, took the lead. The gigantic Persia, which had

been hauled from her dock, was covered with ensigns, and fired salutes

towards evening, while after nightfall rockets were sent up from her decks.

The Saxonia, just arrived from Hamburg, illuminated her rigging, but the

greatest display was made by the Galway steamer, Prince Albert, which

left all other attempts at celebration far behind. A brilliant flight

of pyrotechnics left her deck soon after dark, and immediately thereupon

her spars and rigging were gorgeously lit up with innumerable colored

fires. A national salute was at the same time fired from her ports. Many

sailing vessels also fired salutes and were more or less illuminated.

Fireworks in the

Park

By six o'clock a crowd

had begun to assemble in the Park, and by half-past seven at least one

hundred thousand persons must have been assembled. A denser or more numerous

crowd never stood before the City Hall. The pyrotechnic display commenced

at about half-past seven P.M. with the usual discharge of rockets, beside

which a number of fire balloons were sent up among the stars. After a

brilliant display of these projectile pyrotechnics, together with myriads

of Roman candles, rising and falling in ceaseless ebullition, the "set-pieces"

were lighted. The City Hall itself was illuminated as it has never been

before, a candle being placed in every pane of glass in its extensive

front; but the brilliancy arising from this intense light was paled by

the many-colored glow which was emitted by the pyrotechnics on the front

and wings.

Among the principal devices

was a fiery legend on the west wing to the following effect: "New

York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company - Peter Cooper, President."

Another design had the words, "Atlantic Telegraph Company, William

Brown, President." But the principal feature was the centrepiece

forming the close to the display, which represented a British steamer

and an American clipper-ship, supported by the American and British ensigns,

surmounted by an eagle, on a radiating field, and by the words, "All

honor to Cyrus W. Field." This beautiful device elicited cheer after

cheer from the spectators, who gradually dispersed after its extinction,

and by ten o'clock the Park was nearly empty.

The Illumination

of Broadway

Not only hotels, theatres

and other buildings devoted to the use of the public, but numbers of private

dwellings were illuminated and adorned with transparencies so soon as

night set in. The large hat store near Fulton street was covered with

transparencies, and its neighbor. Barnum's Museum, was, of course, resplendent.

Every window was lit up, and the attendant hand discoursed more lively

music than is usual even at this mirthful place. Tryon row was well lit

up ; hut the splendor of the Astor House threw, metaphorically speaking,

all other illuminations into the shade. On the right of its massive portico

was a transparency with the inscription, "Who hath laid the measure,

thereof, if thou knowest, or who hath stretched the line upon it?"

- Job xxxviii. 5; and on the other side was the quotation, "Let the

floods clap their hands." - Ps. xcviii. 8. Fireworks were displayed

upon the wings, and rockets sent up to mingle with the discharge from

the City Hall.

During the afternoon much

astonishment had been caused in Broadway by the sound of aerial artillery,

and it was not for some time that the gazers upward discovered that the

elevated roar proceeded from a small cannon firing salutes from the roof

of this hotel.

Passing the brilliant Park,

numerous illuminations and transparencies continued the luminous chain,

an important link in which was the brightly lit up establishment of Bowen

& McNamee, with several transparencies, the largest of which bad an

elaborately humorous inscription appropriate to the time.

On the other side of Broadway,

the International Hotel was gorgeously illuminated, displaying also an

international inscription, commencing with the name (in large caps) of

the Queen of Great Britain and ending with that of the President of the

United States.

The other hotels were also

finely illuminated, and the private houses in the higher part of Broadway,

both above and below Fourteenth street, were extensively decorated and

lit up. Still higher up town and in the avenues, as well as through all

the length of the Bowery, bonfires and tar barrels blazed and crackled,

and every engine-house in the city was illuminated, as well as nearly

all the police stations. In fact, New York was in a blaze; but the greatest,

although most unfortunate feature of the occasion was reserved for the

hour of midnight.

Burning of the City

Hall

At a few minutes after

twelve o'clock flames were observed to issue from the clock-tower of the

City Hall, and the bellringer in the cupola was driven almost immediately

from his post by the intolerable heat. As a consequence, the alarm could

not be communicated to the engine-houses, and before the fire-bells elsewhere

could he sounded, the clock-tower was wrapt in flames. The spectacle was

magnificent, and attracted new crowds to the Park, who gazed in admiration

on the destructive grandeur of the burning tower. Nearly an hour elapsed

before the engines began to arrive, and by the time they reached the Park

the clock had fallen in, the statue of Justice - so familiar a sight to

every New Yorker - had disappeared in the fiery glow, and the conflagration

was at its height. Not without difficulty, the flames were at length subdued,

after the total destruction of the clocktower and of part of the roof.

During the fire, officers were stationed at the doors of the Mayor's office,

the Common Pleas rooms, and other apartments, with instructions to remove

the records and valuables in case the fire should spread; but fortunately

these rooms were not endangered. Great damage was, however, caused by

water, and many of the valuable paintings in the Governor's room were

irreparably injured. Fifty thousand dollars are needed to repair the damage

- an expensive addition to the cost of the city's joy!

Financial View of

the Ocean Telegraph in England

Immediately on the receipt

of the telegram announcing the successful laying of the cable, the Atlantic

Telegraph shares of £1,000 each, which were offered at £340, advanced

to a nominal quotation of £600 to £800. Later in the day it was found

that holders were extremely firm, and the final price was £880 to £920.

The first through message from New York is now awaited with the utmost

interest, and most persons connected with the American trade are sanguine

of the permanent impulse it will give to the commercial intercourse of

the two countries, and the economy it will also effect by frequently preventing

the profitless shipment backward and forward of goods or specie.

The financial and general

position of the Atlantic Telegraph Company now appears to be as follows:

Their original paid up capital was £350,000, and this has since been increased

to £459,000, an additional £31,000 having been raised a short time back,

and £75,000 in shares having been created to be handed over in payment

for the exclusive privileges assigned to the company, immediately on the

successful completion of the undertaking. Although the amount to participate

in dividend is £456 000, the capital actually received is £381,000. Out

of this the charge of the entire cable has been paid, together with all

other expenses, and a small cash balance is still in hand, applicable

to the currant outlay. It is understood that the only additional capital

now intended to be raised is the small sum that will bring the total to

£500,000, and which is required for the stations, &c., that remain

to be established.

The colonial concessions

of the company give them an exclusive right for fifty years as regards

the Newfoundland coast and the shores of Labrador and Prince Edward Island,

and twenty-five years as regards Breton Island. They have also a similar

privilege for twenty-five years from the State of Maine. From the respective

Governments of Great Britain and the United States the terms obtained

are a payment of £14,000 per annum from each, for the transmission of

their messages for fifty years, until the dividend amounts to six per

cent. on the original capital of £350,000, after which each Government

is to pay £10,000 a year, such payment to be dependent on the efficient

working of the line. Previously to the failure of the first expedition,

which sailed on the 4th of August, 1857, and lost 383 miles of cable,

the £1,000 shares touched about £1,150 or £1,200, and the lowest point

has been £300, a sale having been made at that price since the attempt

last June, when there was an additional loss of 480 miles. On the present

occasion it appears that nearly 500 miles of cable remain, the total paid

out from the two ships having been only 2,022 miles.

At the latest accounts

the holders of the telegraph shares refused to take less than par to £50

premium.

|

|

August 28, 1858

The Atlantic Cable

The great achievement of a century full

of wonders has spoken; it has greeted America in Victoria's name, and

our President Buchanan has cordially returned the greeting. We have endeavored

to commemorate so great an event by devoting our entire space to illustrating

its principal features, and shall complete the gratifying task in our

next. We may, without any personal vanity, say that ours is the only illustrated

paper whose sketches have been taken on the spot, as our artist was on

board the Niagara from the commencement of the attempt to lay the cable

to its final triumph.

The arrival of the Arabia

puts us in possession of some interesting details, which show that the

Agamemnon arrived at Valentia some short time before the Niagara made

her port on this side, and also that the British vessel had such very

bad weather, that at one time the successful laying of the cable was very

problematical. During four days it blew hard, with frequent violent squalls,

the sea running high; but on Wednesday, the 3d. of August, the weather

moderated, although the sea still continued very much disturbed. It will

thus be seen that the Agamemnon had difficulties to contend with which

the Niagara fortunately escaped.

In chronicling so great an event, it is impossible to calculate its results

upon the world. An English contemporary has said that they cannot fail

to be beneficial, and we heartily echo the wish. For fighting purposes,

England and America are as far oft, as ever, while for the uses of commerce

we are face to face. If Louis the Great boasted that, owing to his statesmanship,

the Pyrenees existed no longer, we can truly say that there is no longer,

an Atlantic to divide the Old and New Worlds; and when two great nations,

are thus brought within speaking distance, the bold broad facts of national

policy are more easily comprehended - or, if misunderstood, the error

can be immediately corrected. It has long been the opinion of our wisest

men that more wars are occasioned by blundering or designing ambassadors

than by real grievances, and in this light the Atlantic cable may be called

the Great Peacemaker between the two chief nations on the globe.

Its effects upon commerce

will undoubtedly be equally great, for although it may not check speculation,

it will materially take from it that gambling character which is so marked

a feature in the commercial world, and which, while accelerating the wheels

of progress, very often makes its onward course the disastrous march of

the Juggernaut. The world is yet in its infancy, so far as social science

is concerned, and we therefore hail every effort made to take from labor

its exhausting toil, and from poverty its sting. This can only be accomplished

when science becomes the handmaid of humanity, and lifts from the shoulders

of man the weight that machinery is destined to perform. In this aspect

every invention is a stepping stone to that great platform on which man

was intended to stand, free, happy and enlightened, when he was made in

the image of a benevolent Creator, who, as he becomes fitted for the privilege,

reveals to him, through the medium of philosophers, mechanics and chemists,

those great secrets which have enabled him now to control the elements,

as he has already done the beasts of the field. We therefore join Captain

Hudson in that reverent spirit which ascribes the glory of this great

achievement to the directing hand of Providence.

|

|

August 28, 1858

Complete Success

of the Atlantic Cable

The telegraph cable is

a complete triumph. Messages are passing over its wires quite freely,

and there is no doubt a short time will enable our electricians to increase

the velocity of transmissions so as to bring it up to those already in

use. It is needless to remind the public how few had faith in such a wonderful

achievement a month ago.

Return to the Atlantic Cables index page |