Introduction: This illustrated plate (one of a set of twelve) makes a satirical comment on the French scientist Jacques Babinet’s skepticism about the viability of the Atlantic cable.

Backmark: Backmark:

L.M. & Cie

Déposé

Creil et Montereau

|

The plates in this set were issued beginning in 1867 by the French firm Creil & Montereau using the trademark L.M. & Cie (Lebeuf et Milliet). Between 1840 and 1876 the company made a large range of transfer decorated plates bearing that trademark. The plates are 8" (20 cm) diameter.

This series of plates is known to historians of the company as “Plaisanteries-6.” The French word translates as “Jokes” or “Witticisms,” and plates in this category make fun of styles, fashions, and events of the time.

I am very grateful to Jacques Bontillot of the website “Les faïences de Creil & Montereau” for providing detailed information on these plates and for the list of all the titles in this series, which is shown at the bottom of this page.

|

Plate No. 6

Detail of the illustration

ÇÀ! LE CÂBLE TRANSATLANTIQUE!

M. BABINET PRÉTEND, LUI,

QUE C’EST UNE BALANÇOIRE.

Here! The Transatlantic cable!

M. Babinet claims it is nonsense.

Notes on the translation:

“Çà!” as an exclamation is literally “This!” but may also be represented in English as “Here!”, “Well!”, or “Now!”

“Balançoire” is literally “seesaw” or“swing,” but also has a slang meaning of “fib; nonsense; stupid joke,” also “poppycock; balderdash; cock-and-bull story.”

Compare this usage with that of the anonymous American skeptic “Observer,” whose January 1859 letter to the Boston Courier was published under the title “Was the Atlantic Cable a Humbug!”

References:

Barrère, Albert. Argot and Slang: A New French and English Dictionary of the Cant Words, Quaint Expressions, Slang

Terms and Flash Phrases Used in the High and Low Life of Old and New Paris. Whittaker & Co., London 1889.

Hérail, René James and Edwin A. Lovatt. Dictionary of Modern Colloquial French (snippet). Routledge, 1984.

|

At first reading, as with so much 19th century satire, the caption on this plate makes very little sense, mainly because we have no context for it. Two dandified gentleman are standing on a rocky shore; one points to the water and says, “Here! The Transatlantic cable!” to which the other responds, “M. Babinet claims it is nonsense.” To understand this, we need more information on M. Babinet.

Jacques Babinet |

Jacques Babinet (1794-1872) was a French physicist, mathematician, and astronomer, a great promoter of science, an amusing and clever lecturer, and a prolific author of popular scientific articles. No matter what the topic, he could be counted on to have a theory (or at the very least an opinion) on the subject: the comet of 1857, meteorology and weather prediction, the metric system, moving icebergs for water supply and climate control, mineralogy and diamonds, aerial locomotion, spiritualism and table-turning, and of most interest here, telegraphy and the Atlantic cable.

Born in 1794, Babinet was perhaps rather set in his ways by the time the Atlantic cable was proposed in 1854. Even after the partially successful expedition of 1858 and the completely successful 1866 cable, he could not be convinced that long ocean cables were the best way to cross the Atlantic. He was well known for his skepticism about the Atlantic cable, having published numerous articles with criticisms of both the existing shorter cables and the 1858 Atlantic cable. He suggested better ways (in his view) to do it; these included constructing artificial islands in the Atlantic, and running the line via a mostly overland route: across Europe, through Siberia and Alaska, and on to the North American mainland.

In August 1866, shortly after the Atlantic cable had been completed, this note appeared in the Journal of the Society of Arts:

The Atlantic Cable.—At a recent meeting of the Academy of Sciences at Paris, a conversation took place on the subject of the Atlantic cable, when M. Babinet, after expressing great doubt as to whether the cable would be lasting, said we ought at least to make it available for a useful purpose. He recommended that we should profit, and that at once, by the electric cable which unites the New World and Valentia, to determine the exact longitude of the American station.

[Journal of the Society of Arts, London, 10 August 1866]

Then in March 1867, the Daily Alta California newspaper published this article about Babinet’s dire predictions for the 1866 Atlantic cable, which had then been in operation for the preceding six months:

The Atlantic Cable – Determination of Longitude

The recent determination of the difference in longitude between Valentia and Trinity Bay with the powerful assistance of the Atlantic Cable, recalls M. Babinet’s urgency, that this problem should be solved before the anticipated destruction of the telegraph. In July [1866], M. Babinet indulged in the most dismal predictions in regard to the fate of the submarine wire, which he declared incapable of resisting the corroding effect of the sea water. He pointed out that the telegraph wire that crossed the British Channel, although eight millimetres thick, was eaten completely through five years after it had been laid down. Also, in the first Atlantic Cable [of 1858], which did not sink to a greater depth than between two hundred and three hundred metres, it was discovered that the wire had worn away into fragments of one or two centimetres in length.

M. Babinet anticipated, therefore, that the brilliant beginning of the present cable would only usher in a period of inevitable calamity, and the morning of its short activity soon be overclouded with the shades of decrepitude and impotence. He explained his seeming ungraciousness in presenting those views at a period of general rejoicing over the success of the great enterprise, by his urgent desire that the brief success be utilized for the solution of the above-mentioned problem of longitude. If, as he supposed it quite possible, the cable should fail immediately after that solution had been obtained, the knowledge of the longitude would have cost some thirty millions, which the world at large might consider knowledge rather dearly bought. But astronomers and geographers would be well satisfied.

It is pleasing to read these predictions six months after they were given, and find that they have not yet been fulfilled, though the problem in whose interest they were made has been satisfactorily solved.

[Daily Alta California, Volume 19, Number 7098, 3 March 1867]

This explains the connection between Babinet and the Atlantic cable, and shows that his long-held view (dating back to at least 1855) that a cable connecting Ireland to Newfoundland was something not to be taken seriously was well known. He was thus a fitting subject for satire once it was obvious that the 1866 cable was a success.

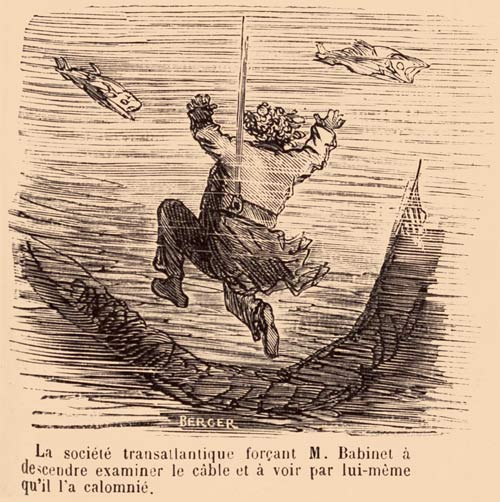

The French weekly illustrated newspaper, Le Monde Illustré, published this satirical cartoon in its issue of 1 September 1866, a few weeks after the opening for traffic of the successful Atlantic cable.

[Artist: Berger. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France]

La société transatlantique forçant M. Babinet à descendre examiner le câble et à voir par lui-même qu’il l’a calomnié.

The transatlantic company forcing M. Babinet to go down and examine the cable and to see for himself that he has slandered it. |

Even five years later, Le Monde Illustré could not resist another dig at Babinet’s dire prophecies for the Atlantic cable. In a story published on 23 September 1871 about the new 8-mile railway tunnel through the Alps at Mont Cenis, the paper wrote:

After the piercing of the Isthmus of Suez, in fact, the piercing of Mont Cenis will remain one of the most wonderful works of our time, one of the most daring challenges thrown by the genius of man to the sphynx of impossibility.

The inauguration of the gigantic tunnel has, as always, proved wrong the hostile prophecies of the routiners, which always begin with the negation. We have not forgotten this good M. Babinet, declaring, six years ago, that if ever we succeeded in laying an electric cable between America and Europe, it would not work for fifteen days.

As illustrated by the satirical plate, cartoon, and written accounts, Babinet, while generally a popular figure, was not universally respected. These extracts from the obituary written by the Paris correspondent of the London Daily News on Babinet’s death in October 1872 give a somewhat different view of the man:

The Late Astronomer Babinet.

M. Babinet, who died on Monday, at his house in the Rue Vaugirard, was of the same generation as M. Thiers. He was one of the few bulky celebrities of the Louis Philippe period who lived to a great age, for at the time of his death he was four years older than the President of the Republic, and only six years younger than M. Guizot. For many years his corpulence became so excessive that he scarcely stirred from his arm-chair.

. . . .

Babinet was not a man of great intellectual grasp, nor a patient toiler. In the bottom of his heart he believed that science could not stir a step beyond what it was when he first wrote about it, thirty-five years ago, in the [Journal des] Débats and [Le] Constitutionnel. He pronounced, I remember, against the transatlantic cable, the Tunnel of Mont Cenis, and different hypotheses which Faraday made the stepping-stones to great discoveries. Faraday and Claude Bernard left him so far behind that the Débats once thought of discontinuing his scientific ‘Causerie.’ But it was found that the readers of that paper would not dispense with Babinet, who made them fancy themselves learned without putting them to the pains of learning.

When possessed of a scientific truth, nobody could present it in a more popular and agreeable form. Babinet was skilled in the art of throwing out a bait to idleness, and giving the grace of table talk to the most abstruse studies. His “Astronomical and Meteorological Encyclopaedia” is still a hand-book in young ladies’ schools. M. Babinet was also celebrated as an ingenious demonstrator, and had the reputation of being the most popular of all the Professors of Mathematics who lectured in the École Polytechnique.

[The Daily News, London, 25 October 1872]

Babinet’s contributions to the Revue des Deux Mondes and to the Journal des Débats and his lectures on observational science before the Polytechnic Association were collected in a number of volumes: “Études et lectures sur les sciences d’observation” between 1855 and 1868. Some of these are available with full text (in French) at Google Books. The volumes of 1855 and 1863 include articles on telegraphy and undersea cables; the articles in the 1863 volume were written in 1860, after the failure of the 1858 Atlantic cable.

I can find no record of anything Babinet wrote on undersea cables after the long-term success of the 1866 Atlantic cable had been demonstrated.

Plaisanteries-6 Title List

None of the other plates in this series have any connection to the cable, but the complete list of titles, courtesy of Jacques Bontillot of the website “Les faïences de Creil & Montereau,” is given here for reference, together with details of plate No.2 as a further illustration of this set.

| No. 1 |

Mrs. les voyageurs d’impériale sur les bateaux-omnibus. |

| No. 2 |

Les nouveaux bateaux-omnibus. Conducteur arrétez....nous

avons nos billets de correspondance. |

| No. 3 |

Cocotte a queue de cheval. |

| No. 4 |

Différentes sortes de balayeuses. |

| No. 5 |

Je ne veux pas vous conduire; les voitures sont libres aujourd’hui. |

| No. 6 |

Ça! Le câble transatlantique! M. Babinet prétend, lui,

que c’est une balançoire. |

| No. 7 |

Dumanet, prêtez-moi votre fusil a aiguille pour

tricoter mes bas. |

| No. 8 |

Comme quoi dans les démolitions on peut être démoli. |

| No. 9 |

Comment! Ces messieurs ne nous invitent pas à diner? Nous

avons pourtant nos assiettes sur nos têtes. |

| No. 10 |

Nouveaux costumes des garçons bouchers, depuis qu’on

mange du cheval. |

| No. 11 |

Pour l’amélioration des chevaux et la destruction des jockeys. |

| No. 12 |

Le cheval de boucherie. |

Numbers 1 and 2 refer to the “Bateaux-Omnibus” service, which began operation in April 1867 to provide river transport for the Paris Exposition. No. 2 is shown below as an example of one of the other plates in this series.

Plate No. 2

Detail of the illustration

LES NOUVEAUX BATEAUX-OMNIBUS. CONDUCTEUR ARRÉTEZ....

NOUS AVONS NOS BILLETS DE CORRESPONDANCE.

The new omnibus boats. Stop, Conductor....

we

have our transfer tickets |

The illustration shows a steam-powered boat, “Le Parisien,” loaded with passengers and heading across the river with smokestack belching. The boat is pursued by frantic would-be customers, hailing its conductor while running after the boat through the waters of the Seine.

The new “Bateaux Omnibus” service was established in Paris in April 1867 to mark the occasion of the Exposition Universelle du Champs de Mars. The boats ran every twenty minutes and traversed the Seine between Pont Napoleon and Point-du-Jour with ten intermediate stops, at a fare of 25 centimes. Another line crossed the Seine between Châtelet and Pont d’Iléna (the stop for the Exposition) every ten minutes.

A contemporary account of the Exposition included this note on transportation:

MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION

The means of transportation, in addition to 6,000 public vehicles (hackney cabs, broughams, livery coaches), 500 pony carriages recently placed in circulation by the Imperial Company, and numerous vehicles called delivery vans, leading to the Quai d’Orsay, consist mainly of these:

Eight bus lines, three for the left bank, five for the right bank (connections with other lines).

Thirty omnibus boats which make the Seine crossing.

The railway, connecting with the various stations of Paris.

|