PACIFIC CABLE 1902-26

SIR SANDFORD FLEMING 1827-1915

The chief advocate of a Pacific cable was Sandford Fleming (later Sir). Born in Kirkaldy, Fife, on 7 January 1827, he emigrated to Canada with his brother and a cousin in 1845, settling in the town of Peterborough. There he took a job with local surveyor Richard Birdsall and then with John Stoughton Dennis, a surveyor based in Weston, Toronto. To provide himself with an income, until he received his certification as a surveyor, he compiled maps of Peterborough, Hamilton, Coburg and Toronto. In 1851 he designed Canada’s first postage stamp, the 3d Beaver. He was also responsible for the introduction of International Time Zones.

Fleming had submitted a plan to the Government for a trans-Canada railway in 1862; this and his continual lobbying for such a scheme led to him being appointed Chief Engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway project in 1871, and the following year, accompanied by his son, Frank Andrew and a friend, the Revd. George Monroe Grant, he began the enormous task of surveying the route.

In the same year as he was appointed Chief Engineer the British-Australian Telegraph Company landed a cable at Port Darwin (later Darwin); this, no doubt coupled with the knowledge that the telegraph would run alongside the Canadian Pacific Railway, brought about the idea of a state-owned Pacific cable. Fleming had always believed that the telegraph should be Government owned.

On his visits to England he lobbied Government officials both for financial help in building the CPR and for the British Government to back the idea (with money) of a state-owned Pacific cable. Regarding the railway, the British Government agreed to guarantee its debts but as far as a Pacific cable was concerned if the Colonial Governments wanted a Pacific cable then they would have to finance it themselves.

BEGINNINGS

A Colonial Conference held in Sydney, New South Wales, in 1877 passed nine resolutions concerning a Pacific cable, one of which authorised the New Zealand Government to approach the US Government to see if they would be willing to pay a subsidy for a cable running from the United States to New Zealand. Whether the approach was ever made is unknown.

In 1879 Fleming wrote to Frederic Newton Gisborne, who at the time was Superintendent of the Telegraph and Signal Service in Ottawa:

“If these connections are made we shall have a complete overland telegraph from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. It appears to me to follow that, as a question of imperial importance, the British possessions to the west of the Pacific Ocean should be connected by submarine cable with the Canadian line. Great Britain will thus be brought into direct communication with all the greater colonies and dependencies without passing through foreign countries.”

The completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, and with it a telegraph line across Canada, strengthened Sandford’s hand. The decision to extend the railway to Vancouver in 1886 helped even more.

Fleming, who attended the 1887 Colonial Conference, obtained the signatures of 21 of the delegates requesting that the Admiralty carry out a survey of the proposed Pacific cable route. The Admiralty’s reply was, ‘That while it was prepared to carry out the work during its normal hydrographic surveys it would not allocate a vessel specifically for the task.’

The following year a proposal was put forward that the UK, Canadian and Australian Colonies each pay a third of the cost of the survey, HM Treasury said it wanted an estimate before committing itself and then the Australian Colonies refused to contribute, so the scheme failed. However, in that year HMS Egeria began a survey which went as far as the Phoenix Islands before being abandoned in 1890.

At the 1893 Australasian Conference held in Sydney the Postmaster General of New South Wales suggested laying a cable from New Caledonia (then about to be linked to Australia by a French cable) to Fiji, Honolulu and San Francisco. The cost, estimated at £3,000,000, was to be shared between the respective Colonial Governments. Nothing came of it, and the New Caledonia cable was abandoned in 1898.

In 1896 Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary, took up a suggestion made by the Canadian Government to set up an Imperial Pacific Cable Committee to look at all aspects of the scheme. It was the first time that the UK Government had committed itself to the project. The Committee, made up of the Earl of Selborne, Colonial Under Secretary and George Murray from The Treasury, representing the UK Government, plus two representatives from Canada and one each from New South Wales and Victoria, met in London on 5 June 1896, sitting until 12 November. In all twenty seven witnesses were interviewed, including Sandford Fleming, Alexander Muirhead, William Preece, and Lord Tweeddale, Chairman of the Eastern Telegraph Company. The Committee issued its report on 5 January 1897 and while the various interested parties received copies the report was not made public until April 1899.

Meanwhile HMS Penguin under the command of Captain A. M. Field RN was commissioned to carry out a survey of Palmyra Island and Fanning Island to see which was the most suitable for a cable station. Captain Field's report, published in 1898, favoured Fanning Island.

REPORT

ON

PALMYRA AND FANNING ISLANDS

AS TO THEIR SUITABILITY AND CAPABILITIES AS

SUBMARINE CABLE STATIONS

BY

CAPTAIN A. M. FIELD, R. N.

H.M.S. “PENGUIN”

1897

HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT

DECEMBER 1897

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE

BY EYRE AND SPOTTISWOODE

PRINTERS TO THE QUEEN’S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY

-------

1898

Report on the Suitability and Capabilities of Palmyra

and Fanning Islands as Submarine Cable Stations.

It is presumed that one of the requisites for a cable station in MidPacific, is the possession of an anchorage where coaling could be carried on under ordinary circumstances of wind and weather, and where coal could be landed with reasonable facility in order to form a coaling depot.

Secondly, that the slopes in the approaches are suitable for laying a cable and that the spot selected for landing the shore end has as much protection as possible from the heavy surf that beats on coral reefs surrounding islands in mid ocean.

The following report shows to what extent these requirements are fulfilled in the two islands, and the work that it would be necessary to undertake to improve existing conditions, where possible.

PALMYRA ISLAND.

PALMYRA ISLAND is an atoll 5 miles in length east and west and 1½ miles broad, with a number of small islets covered with bush and cocoanut trees on its northern, eastern and southern sides. It rises from the centre of a submarine bank, which within 100 fathom limits is 10½ miles long east and west, by 2½ miles broad. Depths of 1,000 fathoms and upward are found at 9 miles distance from the 100 fathom line in an east and west direction, and 2 miles in a north and south direction.

From the shape of the atoll and the direction in which it lies with reference to the prevailing winds, a minimum of protection at the anchorage on the bank of soundings off the western end is afforded, and the distance to which shoal water and rocky patches extend from the reef prevents its edge being approached sufficiently closely to obtain the shelter that might otherwise be had.

There is, however, ample space to anchor in 8 to 10 fathoms water, the bank of soundings being of considerable extent. The tide runs from one to two knots over the bank, causing the ship to be frequently tide-ridden, but H.M.S. “Penguin” found it quite feasible to coal at the anchorage in boats from a collier laying near.

Landing.—The plan of Palmyra anchorage shows the character of the reef and the difficulty attendant upon landing, which is only possible on the western side of the atoll. Elsewhere the sea breaks heavily on the coral reef. Outside the hard edge of the drying reef on the west side, and extending from it to a distance of 9 cables out to the 3 fathom line, rocks and coral patches almost awash abound so closely packed together, with 2 or 3 fathoms water between the coral heads, that it is only with great difficulty that even a skiff can thread her way between them except at high water.

The rise and fall of tide being about 2 feet, a boat larger than a skiff cannot at any time get near the hard reef except at Penguin Spit.

Penguin Spit is the western extremity of a tongue of reef somewhat higher than the reef adjacent to it, extending from the islets on the southern side. This spit is barely covered at high water. On its outer or southern edge the sea breaks heavily, but the force of the waves is expended as they wash over the inner edge of the spit at high water, which at other times is quite dry, with the exception of some gutters that run into the coral from the inside.

On the inner or northern edge of this spit it would be practicable to build an embankment, carrying a small tram line from the islet where the coal depot would be formed, and running out for about 1,000 yards to within a short distance of the extremity of the part. that is shown as dry at low water on the plan, where a small coaling jetty could be constructed for lighters to lay alongside and load up.

The approach from the anchorage to the outer end of Penguin Spit is tolerably clear of rocks and patches, and those that are in the way might be blasted to form a channel by which lighters might pass to and fro.

The distance to the anchorage from Penguin Spit is 1¾ miles, and over a considerable part of it there is a very ominous heave of the sea, which occasionally develops into a blind roller.

Landing a Cable.—The accompanying section B shows the slope at that part of the bank of soundings off the western end of the atoll across which it would be necessary to lay the cable in order to land the shore end at Penguin Spit.

Sections D and A to the north and south respectively are steeper than B and C running off the bank in a W.S.W. and W.N.W. direction respectively.

General Remarks.—The islets toward the eastern end of the atoll are larger and more attractive to form a settlement upon than the western islets, none of which afford any considerable space, but landing being possible only on the western side, and the lagoon being unapproachable by boat, the eastern islets are, to a great extent inaccessible.

The islands have been inhabited at different times, a station once having been made on Strawn Island, and at another time on the islet immediately westward of the observation spot, where there are still signs of habitation, but for a long time past no one has resided here.

Fish are abundant, and curlew and plover may be shot.

The islands seem to be pestered with neither flies nor mosquitos, but land crabs abound.

Water must, as usual in all these islands, be stored in tanks; on the larger islands, doubtless, wells might be sunk, and water for washing purposes (slightly brackish) be obtained.

At low water an extensive area of dry sand is exposed around the margin of the lagoon.

The space available for building a settlement on any of the western islets is very limited, and there is the inconvenience of deep gutters existing between the various islets with 3 to 4 feet water at low tide.

During H.M.S. “Penguin's” stay at Palmyra in the latter half of May 1897 the wind was generally N.E. to E.S.E., light to moderate breezes. Not much rain was experienced during that time, nor in the month of June, whilst a tide party was living on the island in the absence of the ship, but the sailing directions state that for five months rain was almost constant.

FANNING ISLAND

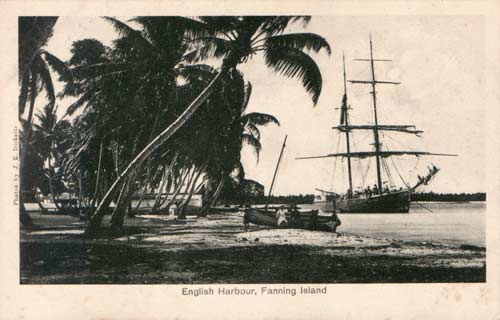

The brig Galilee moored in English Harbour |

English Harbour.—The accompanying plan embraces the whole of the space available for anchorage, in this harbour, the remainder of the lagoon is almost completely choked with reef.

The entrance to English Harbour is narrow, the channel being not more than half a cable in width. The tides run with a strength of upwards of five knots in the narrower parts, and although both flood and ebb streams set straight through, no ship should attempt to enter or leave except at slack water.

Immediately within the entrance points is the outer anchorage, off the settlement, where vessels moor in the full strength of the tide, in a berth so confined that a ship over 250 feet long has barely room to swing.

Three-quarters of a mile further into the lagoon is the inner anchorage in seven to eight fathoms water, where the tides run barely half a knot, and sufficiently spacious for several ships to lay at single anchor. To reach their inner anchorage, however, a ridge or bar of sand and coral four cables in width and carrying only from 12 to 14 feet water must be crossed, and it is, therefore, useless for practical purposes to a ship of any size.

The conformation of Weston Point is such as to produce a slight eddy current inshore on the flood tide, the line of demarcation between the two extending in a N.E. by E. direction from Weston Point. This line constantly maintains its position unaffected b the wind,, and is shown on accompanying diagram.

A small wharf is built in the shelter afforded by the eddy, but it does not extend sufficiently from the shore to enable even a small vessel to make fast alongside it.

H.M.S. “Penguin,” 200 feet in length and drawing 17 feet water lay for a fortnight in safety and comfort breasted off to a distance of 80 feet from the wharf, head to the eastward, with the bow and stream anchors dropped respectively on the port bow and port quarter, and hawsers to the shore. In this berth the ebb tide alone was felt, running about 1½ knots. Except when there is a strong N. or N.E. wind there is no tendency for the ship's stern to swing in to the shore, both ebb and eddy (on the flood) running parallel to the beach, and there was seldom any strain either on the stream, cable, or the quarter hawser to the shore. A vessel 250 feet long might lay in this berth.

There are two alternatives to render English Harbour available for a vessel of the size of a cable ship.

(1) To dredge, blast, or otherwise cut a passage through the Band and coral bar separating the inner and outer anchorage.

The line which the passage would take is shown on the diagram and is 835 yards in length. The material to be cut through is sand overlaying coral; the bottom appears to be strewn with lumps of coral cropping up through the, sand, which is probably a superficial layer with hard coral rock immediately underneath.

Buoys being placed at the positions indicated on the diagram, and also at intervals along the edge of the channel, there would be no difficulty in entering or leaving the inner anchorage at slack water.

It is to be observed that neither flood nor ebb streams set straight through the proposed channel, their directions being inclined to one another at an angle, but as it is only practicable to enter or leave the harbour at slack water, and the tidal streams abreast the position of the channel being at no period of the tide of any great strength, this is not a matter of much

consequence.

(2) Another plan equally effective, and probably less costly than the preceding, would he to utilize the circumstance of the eddy current and to construct a wharf near the position of the present one suitable for a large vessel to lay alongside in safety, bearing in mind the fact that occasionally the wind blows strong from the northward. A comparatively small amount of dredging would be required to obtain the requisite depth.

It has been found when vessels have been laying alongside (or rather breasted off from) the wharf, that unless the line (if the ship's keel is in the line of the ebb stream, that there is a tendency to silt up and form a bank of sand on one bow or the other. No such silting up was observed whilst the “Penguin” was laying there, but it is a fact to be borne in mind in considering any scheme of wharves and dredging.

It appears possible that the curve inwards of the coast westward of Kitty Point may be the cause of the tendency to silt up. A reclamation of a portion of the shallow bank off that point as a continuation of the line of wharf would straighten up the flow of the ebb tide along the sea wall, and while increasing its force slightly it would ensure its running fairly end on to a ship berthed alongside.

Material for reclamation in the shape of loose stones and boulders is to be had in any quantity from off the land immediately behind the settlement, and to clear some of this land of stone would probably be a necessity in any case, in order to obtain sufficient space for the buildings and grounds necessary to a cable station. At present the habitable space is of limited extent, and what there is is all in the occupation of Mr. Greig. Extension of the harbour frontage by reclamation is therefore all the more desirable. The diagram shows the proposed reclamation and wharf with a ship 370 feet long berthed alongside. On this diagram also is shown the position of mooring buoy E, which it would be necessary to lay down for the purpose of hauling off from the wharf, which can only be done on the last of the ebb tide, and then allowing for the first of the flood to swing the ship preparatory to going out. A warping buoy D is necessary to ensure canting the ship's stern sufficiently as the ebb tide slackens, in order that the flood may take her on the starboard quarter to swing the ship in the required direction, whilst a bow line to C assists the operation of turning and prevents the ship from swinging into the shallow water which is only half her own length from the mooring buoy E. The interval of absolute slack water is very short, not more than five minutes at the outside, and the tide very quickly begins to run with force, therefore care, judgement, and promptness in working the hawsers is absolutely necessary, but by swinging the ship on the three buoys it is believed that no undue risk would be taken, and that it would be unnecessary to incur the expense of the additional dredging required to enable a large ship to swing absolutely clear in either direction from the mooring buoy.

A buoy is required at B to mark the edge of the shoal ground off Weston Point, and B and D are so placed that when in line they form a leading mark for entering or leaving the harbour.

Both C and D, besides their primary object as warping buoys, mark the edge of the shoal ground on the north side of the harbour.

A fairway buoy at A is desirable to mark the edge of the shoal ground on that side of the channel. Coming alongside the wharf on the beginning or last of the ebb wound be a matter of no difficulty.

Coal Depot.— There is already a coal store near Kitty Point, and tram line from it to the wharf; there is space to enlarge the store to any extent required. At present there is 200 tons of

coal in. the store, but it has only been placed there as a speculation, and it is by no means likely to be replenished.

Whaler Anchorage.—In the event of neither of the foregoing schemes being considered practicable, there is yet a third plan that might be adopted. Whaler anchorage is of a small indentation of the coast 3 miles north westward of the entrance to English Harbour. A plan of this anchorage has been made on a scale of 8 inches to the mile.. It is sufficiently spacious to

allow a ship of moderate size to anchor in 10 fathoms with ample room to swing, but a larger ship would have to anchor in 20 fathoms.

If moorings were laid down a cable ship might lay here in security, sheltered from the prevailing wind and swell. Westerly and southerly winds doubtless make the anchorage unpleasant, but they are of comparatively rare occurrence. Except on these occasions landing is perfectly easy on a sandy beach through a narrow gutter in the coral. The points of reef which project from two points of land form a small sheltered bay in the coral reef. At this anchorage guano used formerly to be shipped, and a settlement existed here at one time; there is a well of fresh water close to the beach.

There are the remains of two white posts on the shore which mark the landing place, a bearing of which was useful for anchoring upon.

Coaling.-- If this anchorage were made the head-quarters of the cable ship, coaling must be carried out by lighters towed round from English Harbour, where it would be necessary in any case to fix the coal store.

Landing the Cable.—Sections of the slopes (drawn to the same scale vertically and horizontally) were obtained off English Harbour, off Whaler anchorage, and off the northern point of the island. Of these sections, section C (off northern part of island) is on the whole the most gentle, but there is no protected spot there for landing the cable, the surf breaking heavily on the reef. From 66 to 119 fathoms depth the slope is at an angle of about 45% and also from 184 to 248. The slope between 300 and 400 fathoms is also somewhat steep, but with these exceptions the slope is moderate.

Whaler Anchorage (Section B).—In two places, one between 65 and 100 fathoms, and the other between 114 and 144 fathoms, the slope is 70° and 60° respectively. Elsewhere on the section the slope is moderate. This landing-place has the great advantage of being accessible and protected, but in the two places specified the slope is steeper than on either of the other sections. In all other respects it is by far the best place to land a cable anywhere along the outer coast of the atoll, and it is easy of access from English Harbour either by sea or by land.

English Harbour (Section A).—The slope is perfectly oven, at an angle of 10° with the horizontal, out to a depth of 32 fathoms, when it suddenly drops down to a slope of 40° which it maintains with remarkable regularity. The strong tides would probably cause considerable wear on the cable if brought in through the entrance. Weston Point is of shingle and loose boulders. and the tide runs very strongly off it.

The atoll itself is the summit of a submarine mountain, the shape of which follows roughly the general shape of that portion above water. The 1,000 fathom line is found at a distance of 7 miles from the reef in a north-westerly direction, and probably at a distance of about 9 miles in an easterly direction from the eastern end of the island, but this limit was not actually determined. On the N.E. and S.W. sides of the atoll the 1,000 fathoms line approaches it to within 3 or 4 miles, the slope, as shown by the soundings, being fairly uniform from the 1,000 fathom line upwards to the reef.

The best approach for a line of cable from the north-eastward would probably be found round the north-end of the island.

General remarks.—Fanning Island belongs to Mr. G. B. Greig, who was born on the island and continues to reside there with his wife and family. His father, the late Mr. Wm. Greig, acquired the island by purchase some 40 years ago. Mr. Wm. Greig died a few years since, and is buried in the cemetery near the settlement, which is situated close to the beach between Weston and Kitty Points, which forms the southern entrance point of English Harbour.

The island produces copra, guano, and arrowroot, the latter in sufficient quantities for home consumption only. The guano used formerly to be extensively worked, but being of an inferior quality the workings have ceased for some years past. Copra is the staple product, and a considerable quantity is exported annually. The various islands on the margin of the atoll are planted abundantly with cocoanut trees, but the best bearing trees are situated principally in the immediate vicinity of the settlement.

Pearl shell is found in the lagoon, the shells are of somewhat small size and are not dived for systematically. Fish of excellent quality abound all over the lagoon, and great quantities were caught by seining. The total population, men, women and children, is about 40 at the present time, all in the employ of Mr. Greig.

A schooner from Honolulu visits the island on an average twice a year, usually in June and December. She is chartered by Mr. Greig to bring supplies, and to ship the half-yearly produce. Mr. Greig's agent in Honolulu is Mr. John S. Walker.

Settlement and Coconut Plantation on Fanning Island |

The general appearance of the settlement is very pleasing. Two well built and commodious dwelling houses stand a short distance back from the sandy beach facing the harbour, fronted by a turfed lawn, shaded. by cocoanut trees, dotted about it. Several store houses and out-buildings systematically arranged occupy other parts of the lawn, whilst the native quarter is situated further back in the direction of Kitty Point, and out of sight.

Close to the native quarter is the cemetery, and behind that again, at a distance of ¼ mile, is a fresh-water lagoon well stocked with fish.

Abruptly contiguous to, and in striking contrast with this attractive corner of the promontory, is a howling wilderness of barren stone-covered ground, whose limits push themselves right up to the back of the settlement.

The land upon which the settlement is formed was never of this character but of a sandy nature. upon which the turf grow readily when laid there, and it is difficult to say what amount of labour might not be necessary to render this stony waste habitable.

The northern entrance point, north and westward of Cartright Point, presents more promising features, the ground being sandy and cultivated with cocoanut trees, but the immediate vicinity of Cartright Point itself is rocky, and landing is much more inconvenient on that side. In fact the present settlement occupies by far the most desirable situation on the island, but the space is so limited in area that new buildings would inconveniently encroach upon the present occupier. That difficulty being surmounted, the situation for a Cable Station meets every reasonable requirement from the point of view of habitability.

The climate appears to be healthy and pleasant. At times a considerable quantity of rain falls, but during the “Penguin's” stay in June 1897 there was little or none to speak of.

Drinking water is collected in tanks, but numerous wells have been sunk for water for washing purposes, and it is only very slightly brackish.

Cattle, pigs, and poultry are kept by Mr. Greig, and he has a small garden in which bananas, plantains, and papaws are grown.

Curlew and plover may be shot.

RELATIVE MERITS OF PALMYRA AND FANNING AS CABLE STATIONS.

From the foregoing remarks on the capabilities of, and the facilities offered by the two islands, it will be apparent that the latter is in every respect better suited for the purpose. The difficulty of landing at Palmyra is a serious defect in itself, whilst the singularly broken up character of the reef renders any attempt to construct a landing place a very costly operation. When constructed, the long distance to the anchorage and the heavy swell with blind rollers would render the passage of lighters to and fro dangerous and coaling tedious.

In respect of climate there is probably not much difference, but in everything else that appertains to comfort of living, Fanning Island is greatly superior.

As regards facilities for landing the shore end of the cable, the slopes at Fanning are not greater than those at Palmyra. At Whaler anchorage, it is true, there are two very abrupt falls in the otherwise moderate slope, as also off the north part of the island, but at English Harbour the slope is singularly uniform and moderate for the edge of a coral atoll rising out of deep water, and the additional wear and tear caused by the action of the tide could no doubt be suitably provided against.

The only remaining point of comparison is the facility offered by each island as anchorage for a cable ship. At Palmyra there is abundance of room in moderate depth of water, but with strong tides causing the ship to be generally tide ridden and at an inconvenient distance from the shore.

At Fanning, on the other hand, by the first scheme herein submitted, the ship lays in the inner anchorage out of the tide; and by the other alongside a wharf, and the cost of either scheme must be balanced against the expenditure absolutely necessary to be incurred at Palmyra before it could be thought of as a cable station.

In the event of neither scheme being entertained there yet remains the possibility of her being able to lay permanently at Whaler anchorage at moorings laid down for her, coaling being carried out from English Harbour, at a distance scarcely greater than it would he necessary to effect it at Palmyra, but under conditions infinitely more favourable.

On the above grounds, therefore, I am of opinion that Fanning Island is the more suitable island of the two for the purposes of a cable station.

| H.M.S. “Penguin” |

A. MOSTYN FIELD, |

| HONOLULU, 6th August 1897. |

Captain. |

Following this report the route selected was: Vancouver - Fanning Island - Fiji - Norfolk Island - New Zealand and Australia.

THE PACIFIC CABLE BOARD

Christmas card issued by the Pacific Cable Board in 1904 |

|

On 4 July 1900 Joseph Chamberlain held a meeting to set up the Pacific Cable Scheme, which would lay down the terms and conditions of the operation of the Pacific Cable. The Board consisted of eight members, three from the UK, two each from Australia and Canada and one from New Zealand, these members would in turn select the Chairman. The British Government raised £2,000,000 at 3% to cover the cost of construction. Should the scheme fail the British Government was only responsible for 5/18 of the loan, the rest being split between, Canada and Australia 5/18 each and New Zealand 3/18. Profits or losses in operating the cable would also be shared out in the same way. Tenders were asked for and four had been received by October. Of those four Telcon’s was the lowest at £1,795,000. Permission was given to accept Telcon’s price and the contract was awarded on 31 December.

/Britannia(2)_s.jpg)

CS Britannia (2) |

The following is taken from the log of Captain S.A. Garnham, who was Third Officer on CS Britannia (2) at the time. He was First Officer on CS Dominia during the laying of the 1926 ‘loaded cable.’ During WWI he served on CS Telconia.

We left London for the Pacific on March 6th 1901. On the way we laid 130 miles of cable from Adelaide and buoyed it off Kangaroo Island.* Whilst buoying, the cable got foul of the propellors on account of the strong current; it took us six hours to get it clear, but no damage was done.

* This was the shore end and intermediate cable for the cable being laid from Cocos (Keeling) Islands via Perth.

On May 7th Britannia anchored in Sydney Harbour for coal, and on the 20th we arrived at Brisbane, where we saw the King and Queen, then Duke and Duchess of York. At Brisbane a cable house was built by the ship's people, Britannia having brought the material out from home.

On May 27th we started sounding towards Norfolk Island, and on the 28th we got a sounding of only 226 fathoms after getting 2,470 fathoms. A buoy was immediately put down and soundings were taken within a large radius for four days for the purpose of finding the most level bottom. There was no error; we had found a range of submarine mountains, and they are now known as the Britannia Hills.

On May 29th we had the misfortune to have a fireman die through breaking a blood vessel. The following day the ship was stopped and the man was buried, the Captain reading the Burial Service and all hands attending.

Heavy gales were experienced for two days with very heavy seas that continually swept over us, preventing us from taking any soundings. On June 12th we arrived off Norfolk Island and sounded in various bays to find the best place for a cable landing. Whilst there we landed the material for building a cable house, this being built by the islanders. At this time Norfolk Island had about 800 inhabitants who had been transferred from Pitcairn Island. These people are descendants of the mutineers of H.M.S. Bounty1. Round about 1856, that is,

when the first Atlantic cable was being laid, Norfolk Island was then a Convict Station.

1. The mutiny of the Bounty took place on April 28, 1789. The mutineers put Captain Bligh and 19 men into an open boat with a small stock of provisions; these reached Timor in June after a voyage of nearly 4,000 miles. Six of the mutineers were condemned and three executed. Those mutineers who escaped with the Bounty were not discovered on Pitcairn Island until 1814.

We left Norfolk Island on June 21st and commenced sounding towards New Zealand, anchoring in the Bay of Islands on the 29th and then sounding in various bays to find a good spot for the landing. Again we landed material for a cable house. We coaled at Auckland and returned to Norfolk Island, proceeding thence towards Fiji.

On July 18th we got a sounding of 800 fathoms after getting over 2,000 and we had to run back about 15 miles to find a better and more level route. All the way between Norfolk Island and Suva, Fiji, we found the bottom very uneven, which delayed us considerably whilst we found a better bed for the cable. We landed material for a cablehouse, and on August 3rd proceeded towards Fanning Island.

We found the deepest depths of this expedition between Suva and Fanning Island, reaching as much as 3,410 fathoms.

At a sounding of 2,960 fathoms we got a temperature of 35 degrees Fah., the surface temperature being 81 degrees Fah.

We arrived at Fanning Island on August 23rd and built the cable house, the ship's people taking the material ashore in our lifeboats. On account of the shallowness of the water we had to get out of the boats and carry the gear, an uncomfortable business. Before building the house we had to cut down trees and bush. We left six of the crew ashore for three days to finish building the house whilst we went away to take further soundings, leaving them hammocks to sleep in, and food, etc. On our return they said that they had been unable to sleep on account of the white ants which swarmed all over them. Leaving Fanning Island on August 27th we took about 25 soundings and then set course for Honolulu.

Pacific Cable Station, Fanning Island |

The total number of soundings we took on this expedition was 664, the greatest depth found being 3,410 fathoms. We lost 11,700 fathoms of wire, through its kinking and snapping under the motion of the ship, 14 snappers and 7 thermometers.

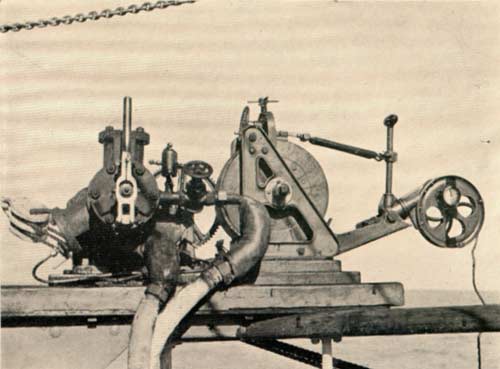

Lucas Sounder |

Taking a Sounding |

QUADRA

The Canadian steamer Quadra set out in March 1901 to find a suitable landing site for the cable and after examining the area around the Jordan river and Port San Juan sailed into Barkley Sound and found that Bamfield would be ideal. The sea bed consisted of black ooze and was free of rocks and the beach sloped gently. Other things in its favour were lack of electrical interference and little danger of the cable being fouled by ships anchors.

HMS EGERIA

HMS Egeria, at the time based in Esquimalt, British Columbia, undertook a series of soundings around Bamfield, under the watchful eye of W.P. Daykin, lighthouse keeper at Carmanah Point Lighthouse. He logged the following.

| 12 July 1901 |

British man-of-war two miles SW off here all afternoon with her boom strung out. I hoisted our ensign and saluted. She answered. |

| 13 July 1901 |

The man-of-war still to westward. She seems to be taking soundings. |

| 14 July 1901 |

Man-of-war still at anchor in same place. Had several boats down. |

| 15 July 1901 |

Man-of-war Egeria still west. |

| 17 July 1901 |

The Egeria still surveying off Barkley Sound.

6pm Egeria sounding off Bonilla Point. |

| 21 July 1901 |

Egeria in San Juan |

| 22 July 1901 |

Egeria heading west. |

| 27 July 1901 |

Egeria still surveying. |

| 29 July 1901 |

Egeria passing Cape Flattery inbound. |

| 24 Aug 1901 |

Egeria outbound. |

BAMFIELD CABLE STATION

Bamfield Cable Station

The original station, at the top of the hill, was designed by Francis Mawson Rattenbury. The new station, nicknamed ‘Alcatraz’ by the staff can be seen to the left and below the first station. A present-day view of the cable station site may be seen on this page. |

On October 9, 1901, the Victoria Colonist newspaper reported that:

A telegraph construction party left Victoria on the coastal steamer Queen City bound for Bamfield. It consisted of: J. Wilson, superintendent of Canadian Pacific Telegraphs, Mr. Cambie, chief engineer of C.P. Telegraphs, Mr. Cartwright, assistant engineer of the Lulu Island Railway and Mr. Lockwood who was in charge of the arrangements. The actual construction would be done by workmen who would be sent as soon as these preliminary arrangements had been completed.

The ever watchful W.P. Daykin made the following entries in his log.

| 21 April 1902 |

Queen City arrived southbound with a large gang of men going to the cable station in Bamfield. |

| 15 September 1902 |

Alberni and Bamfield (landline) wires within four miles of each other. |

Once the site had been cleared of trees and scrub work began on building the station, the main building being designed by Francis Mawson Rattenbury, one of British Columbia’s leading architects. He also designed the British Columbia Parliament Buildings, the Empress Hotel and the Vancouver Courthouse. The construction work including the manager’s house and twelve bungalows for married couples was undertaken by the Canadian Pacific Railway, along whose line telegrams would be telegraphed to Montreal and eventually to England. The main building contained 50 rooms, including offices, maintenance rooms, dining room, billiard room, library containing 3,000 books and quarters for the bachelors on the staff. The first messages transmitted over the new cable and then around the world were sent on the 1st November 1902. The service opened to the public on 8 November.

The decision to lay a loaded cable from Bamfield to Fiji brought about the need for a new cable station which was built below the existing building. The new building built of concrete was given the nickname of ‘Alcatraz’ by the station staff. The original building then became the bachelor quarters. All this including the cable laying took place in 1926. In 1929 the Pacific Cable Board became part of Imperial & International Communications Ltd., which in 1934 became Cable & Wireless Ltd., then in 1950 the Canadian Overseas Telecommunications Corporation (COTC) took over the assets of C&W in Canada including the Bamfield station. A new cable station was built at Port Alberni opening in 1959 and Bamfield closed with the last messages being sent on 20 June 1959. 1965 saw the demolition of the original station along with a number of other buildings. The site was purchased in 1969 for conversion into a Marine Research Centre which opened in 1972.

Anglia laid the following cables:

| 8-18 March 1902 |

Southport, Australia ‑ Norfolk Island 837 nm. |

| 20‑25 March 1902 |

Doubtless Bay, New Zealand ‑ Norfolk Island 519nm. |

| 3‑10 April 1902 |

Norfolk Island - Suva, Fiji 980nm. |

On completion Anglia returned to the UK to load the 2046 nm of cable for the section between Fiji and Fanning Island, which was laid between 17 and 31 October 1902 completing the contract two months ahead of schedule.

Colonia arrived at Victoria on 12 September and after taking on coal and other supplies at the British Naval Base at Esquimalt left for Bamfield.

W. P. Daykin records the following in the lighthouse log:

| 17 Sept 1902 |

Colonia leaves Victoria on for cable station (to commence laying Pacific cable).

Colonia passing outbound. Signalled her but received no answer. |

| 18 Sept 1902 |

Cable ship Colonia left Bamfield at 3.30 pm (commenced paying out cable). |

Colonia reached Fanning Island on 8 October, completing the laying at an average speed of 8 knots, a record. This 3459 nm cable and the one laid in 1926 were the longest telegraph cables ever laid.

FANNING ISLAND

Coastal Scene, Fanning Island |

Fanning Island is one of the main Line Islands and is situated about 1600 miles east of Tarawa and about 150 miles north west of Christmas Island. Known as Tabuaeran locally it was discovered on 11 June 1798 by Edmund Fanning, Captain of the US brig Betsy, on a voyage to China.

In 1846 two British subjects Messrs Lucett and Collie who had been living in Tahiti landed on the uninhabited island with a number of natives to harvest coconuts. They sold the rights to C. B. Wilson in 1851, he later sold them on to Captain Henry English. On 7 April 1857 English applied to the British Consul in Honolulu for permission to hoist the British flag on the island. Consent was given. Formal possession of the island was taken in 1861 by HMS Alert and annexation by HMS Caroline took place in 1888 when plans were being drawn up to lay a cable across the Pacific.

In 1859 English entered into a partnership with William Greig and George Bicknell and these three were joined by William Owens, owner of Washington Island, in 1860. Owens left the following year and English retired in 1864. Messrs Greig and Bicknell were confirmed as

lawful owners of both Fanning and Washington Islands by the British Consul in Honolulu on 2 September 1864. The Greig-Bicknell partnership lasted until 1906 when they sold out to Father Rougier who in turn sold it on to Fanning Island Plantations Ltd., a Burns Philp subsidiary.

S. M. Kl. gesch. Kreuzer Nürnberg

am 8. 12. 14 in der Seeschlacht bei den Falklandsinseln gesunken

SMS Nürnberg landed an armed party on Fanning Island on 7 September 1914. Sunk with all hands on 8 December 1914 in the ‘Battle of the Falkland Islands’ |

Like Cocos, Fanning Island received a visit from the German Navy. On 7 September 1914 the cruiser SMS Nürnberg, flying the French flag and accompanied by SMS Leipzig approached Fanning Island. Landing an armed party the Germans set about wrecking equipment and cutting the two cables. They also took 3000 gold sovereigns from the safe, used to pay the staff, plus £71 in stamps and cash from the Post Office. Shortly after this incident the Nürnberg was sunk, with all hands, in an engagement with the Royal Navy known as the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

The decision to land COMPAC at Hawaii instead of Fanning Island brought about the closure of the cable station at the end of 1963. In 1964 it was taken over by the Hawaiian Oceanographic Institute as a Pacific Equatorial Research Laboratory for the study of Equatorial Currents.

CHANGES

Due to the continual breakdowns on the landline between Bamfield and Port Alberni HMCS Iris (1) laid a cable between these two points in 1903. In 1912 the same vessel diverted the Norfolk Island - Doubtless Bay cable into Auckland. At the same time CS Silvertown, owned by the India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Works Ltd., laid a cable from Sydney to Auckland. The company manufactured the 1225 nm cable at their factory at Woolwich Reach on the Thames.

In 1923 CS Stephan laid a cable from Southport to Sydney to replace the land line and a duplicate cable from Fiji to Auckland. The cable was made by the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company at Greenwich.

1926 LOADED CABLE

The Pacific Cable Board thought of duplicating the Bamfield - Fanning Island - Fiji section of the Pacific cable as early as 1912. The Board also considered the use of Wireless Telegraphy, though nothing came of either scheme.

CS Dominia |

In 1926 the Pacific Cable Board finally decided to duplicate the cable along the busiest section of its route, namely Fiji - Vancouver. It was to be a ‘loaded cable’ The Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company Ltd., were awarded the contract to lay thesection Bamfield - Fanning Island and they used CS Dominia specially built to lay the cable. Siemens Bros were awarded the Fanning Island - Fiji section and used CS Faraday (2) to lay the 2043 nm cable.

-Crew-01_s.jpg)

Ships Officers CS Faraday (2)

Board reads:

PACIFIC CABLE BOARD

1926 FANNING ISD – FIJI

CABLE EXPEDITION |

-Crew-02_s.jpg) |

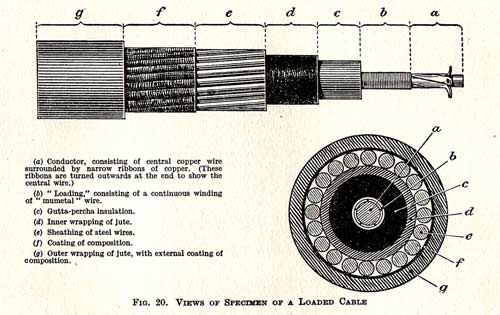

A loaded cable has an additional winding of a metal alloy around the conductor. The one developed by the Telegraph Construction Maintenance Company Ltd., consisted of an alloy of nickel, cobalt and iron and was named ‘Mumetal’ and was manufactured as a wire. It gave up to a tenfold increase in transmission speeds. ‘Permalloy’ developed by the Western Electric Company was a nickel-iron alloy manufactured as a tape 0.13 in. wide which gave up to a fourfold increase in transmission speeds. Siemens Bros used Permalloy on their cable.

Overall a transmission rate of 1000 letters per minute (against 200 on the old cable) was achieved over the whole of the new cable. As the peak periods for traffic occurred at opposite times of the day, peak traffic going from England to Australia would be sent over the new cable, with the reverse traffic, which was considerably lighter, being sent over the original cable and vice versa.

As with the Canadian Government, the Australian and New Zealand Governments eventually took over the assets of Cable & Wireless, forming state owned Commissions to operate the various cables. Following the laying of COMPAC in 1963, the Pacific Cable was withdrawn from service in 1964.

Loaded cable |

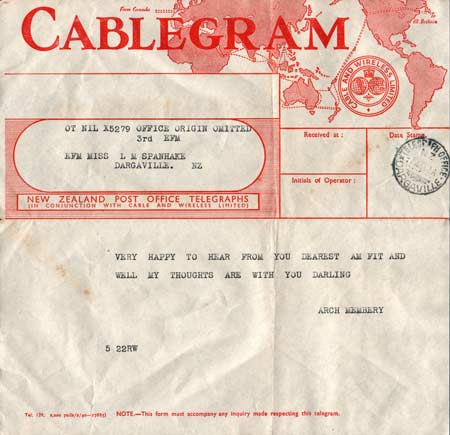

1942 New Zealand Cablegram, sent over circuits of Cable & Wireless |

SOUTHPORT CABLE HUT

The last change to the Pacific Cable system prior to its closure was probably the 1951 replacement of the cable hut at Southport on the Gold Coast of Australia. The cable station site itself was sold in the 1960s and redeveloped in the 1980s, but two of the original station buildings were relocated to the Southport School nearby and are on the Gold Coast Local Heritage Register, as is the 1951 cable hut.

The City of Gold Coast Council is actively promoting the conservation of the Southport cable hut, and the information and photographs here are courtesy of Jane Austen, Coordinator Cultural Heritage Development, and the City of Gold Coast. Thanks also to Colleen Yuke of the Gold Coast Historical Society and Museum for the initial contact about the cable hut.

From the Conservation Management Plan:

The surviving Cable Hut is the second hut, built in 1951 as a replacement of the original constructed in 1902. The 1951 Cable Hut is constructed in face brick and is located in the open space reserve named Cable Park. The Cable Hut is entered in the Queensland Heritage Register as the surviving evidence of the crucially important Pacific Telegraph Cable. The installation of the Pacific Telegraph Cable line commenced at Southport in 1902 and following completion across the Pacific Ocean to Canada operated for many decades through both World War 1 and World War 2. The Cable Hut and nearby Cable Station at Southport were closed in 1962.

Cable Park in 2016, showing the route map plaque and the cable hut |

Cable route map plaque |

Cable hut exterior with cable section and descriptive plaque |

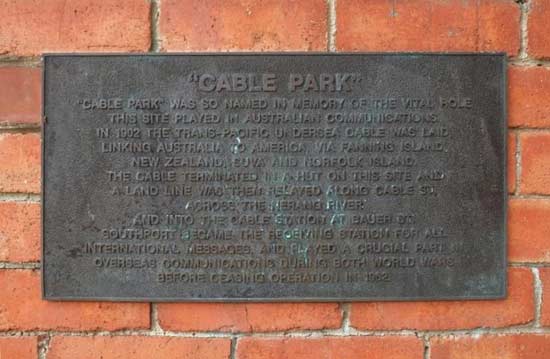

Descriptive plaque mounted on outside wall |

Cable section mounted on outside wall |

Cable hut interior

Black-coated cables are the undersea sections;

grey wires are the onbound land connections |

Detail of cable terminations |

Cable tags for the NI (Norfolk Island) section |

Detail of pressure gauge |

|