Introduction: These pages present personal aspects of cable-making at Greenwich, by some of the craftsmen who worked there.

Jim Jones, now retired, worked in the

cable industry at Greenwich for many years, beginning his apprenticeship at Telcon as a carpenter in 1959. Jim shares these photographs

of cable work at the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company

(Telcon), and Standard Telephones & Cables (STC). Other members

of Jim’s family also worked in the cable business.

|

Jim writes:

I worked at the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company (Telcon) from 1958 until 1966, and at STC (Standard

Telephones & Cables) from 1979 to 1989.

I started as an apprentice in September 1958 as a carpenter

/ joiner / wood-machinist. I made the troughs for repeaters to run in

on CS Monarch, and worked on CS Ocean Layer extending the

hospital area half-deck the last time the ship was at Greenwich—caught

fire later. I also worked on CS Mercury making modifications to

the radio room, and on other cable ships.

Telcon metal plaque, about 8” x 6”, fitted to all

machinery sold |

Just to sidetrack a bit, while I was a 16-year-old

apprentice in 1959, Sir John Dean had his drop-down continental Bentley

in the Telcon garage. I couldn’t resist and sat in it! No sooner than

I sat in the car he came back and caught me. “Bugger, I’m going to

get the sack”, I thought. He came up to me he said “Do you like

this car?” “Brilliant”, I said, still expecting the sack.

He then told the chauffeur to drive me around Greenwich with me sitting

in the back, still wearing dirty overalls. When I got back, I got out

of the car, he put one hand on my

shoulder and shook hands with the other, and said “Maybe, son, one

day you could have a car like this”, wished me luck and went. Did

I get some ribbing from the others on site!

While at Telcon, I also did maintenance on the factory

site, loaded and unloaded freighters with telephone cable and power cable,

and worked on dismantling the PLUTO pipeline machine in 1959.

My father ran a cable-making machine, my uncle was

an engineer for cable ship running gear, and my elder brother was a blacksmith

at Telcon, working on chains, grapnels, etc.

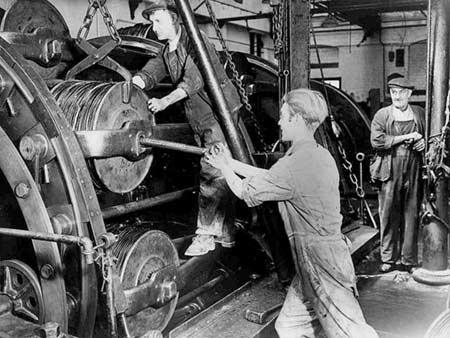

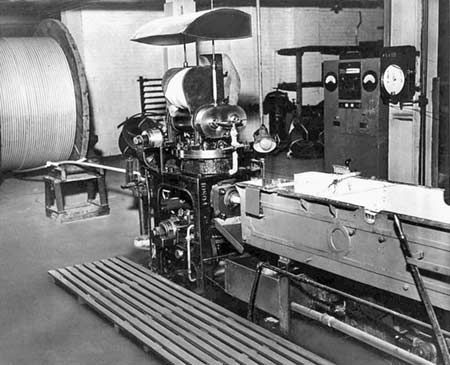

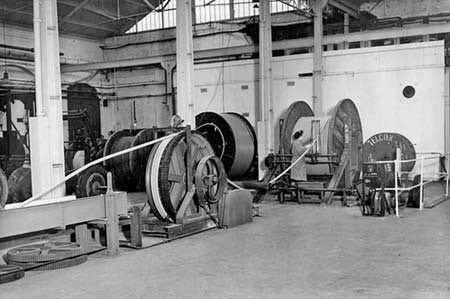

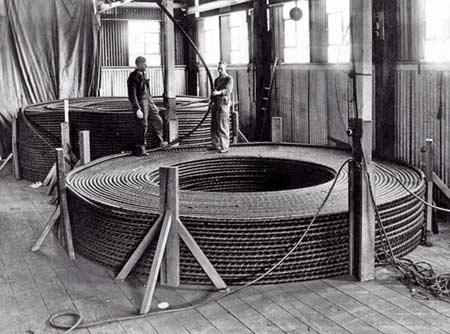

The first group of photos show cable manufacture at

the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, Greenwich, circa

1948.

| Click on each photo

for a larger view. |

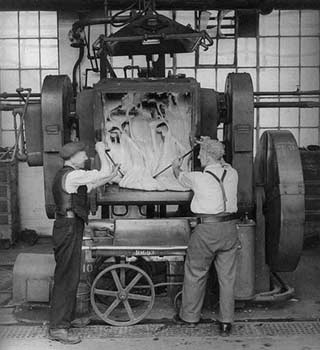

Machine for shaving gutta percha and balata |

|

Gutta Percha mixing machine |

|

|

|

|

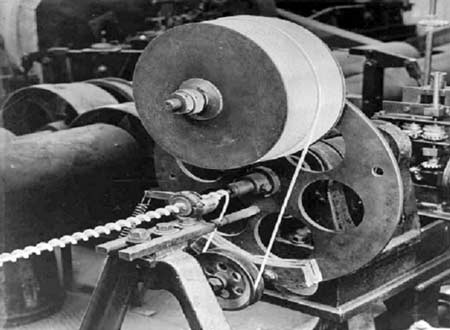

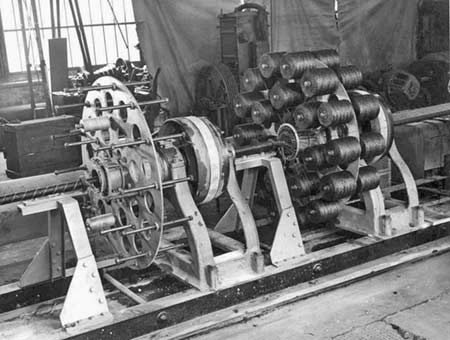

Cable armouring machine |

|

Cable armouring machine |

|

Weaving the armouring wires around

the cable |

|

|

|

Finished cable—short runs stored

on reels |

|

Finished cable—long lengths stored

in coils |

|

Cable coiled into tank for underwater

testing |

|

War time—Chief Fireman Big Jim’s

tin hat |

Tin hat worn during the war in Malta

by an ex-STC man named Reg Burningham, keeping open the telephones on lines

for the RAF |

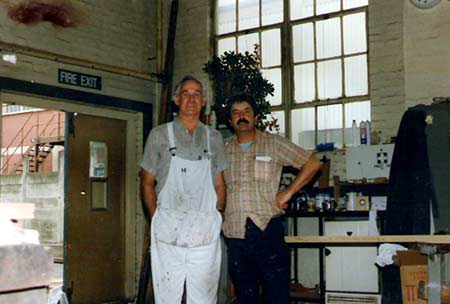

The next group of photos are of the carpenters’ shop at STC

in the 1980s. The Standard Telephones & Cables (ex Telcon site

or Submarine Cables, now Alcatel Greenwich) carpenters’ shop is where

Jim Jones resided when not working for the Projects Department. |

|

|

|

Left to right: Derek Chapman -site painter;

(Taffy) Edward Bradley—shop chargehand;

Tony—carpenter. |

|

My toolbox. Photo on shelf may be CS

Monarch loading cable at Greenwich, 1950s |

|

Dinner break in the sunshine at the

rear of the carpenters shop:

(left) Jim Jones—carpenter/joiner/wood machinist;

(right) Mick

Toomey—carpenter’s mate. |

|

(Left) Derek Chapman—site painter; (right)

Jim Jones |

|

Jim tells this story of life as a carpenter (and much more) at STC:

During the late 1980s John Gaylor from the projects

department came to the carpenters on a Monday, and told me that

some terminal equipment installed in Spain was being taken out again

and brought back to UK. I said “OK, what’s that got to do with

me?”

He told me that there was a problem—because of new EEC rulings

on health & safety, noise levels of the terminal equipment when

running have got to be in the contract. I said, with a long y-e-s, “I still don’t understand what that’s got to do with me.”

He explained that the company had chartered

a plane to bring the equipment back to be tested for noise levels,

and contacted British Aerospace sound testing chamber, but they

were fully booked. They tried other places which were also unavailable.

He asked me if I could build a large enclosed sound testing chamber,

10 square feet. “Probably,” I replied, “Off the top of

the head estimate, it would take about two and a half weeks.”

I asked him when the noise levels had to be

on the contract. “Next Friday [in five days time], or the company

may have to start paying out £2 million in penalties.”

“Five days!” I replied, “You

must be joking!”, but I told him that if there was no alternative

we would just have to have a go at it, and that I would phone the

suppliers and see if they could deliver materials today. “See

what you can do, money is no problem in this case.” So I told

the supplier that if he could deliver all the materials: wood, sound

proofing, etc, now, he could double the price. The materials

arrived 4 hours later!

Mick Toomey and myself got stuck into the job,

and on Friday, five days later, about 4:30 pm, we were just finishing

the sound testing room, and even gave it a sliding access door.

We turned round and the terminal equipment for testing was being

pushed into the chamber, along with the sound testing equipment.

The door was shut, and ten minutes later, with STC management and

staff from the terminal constructors waiting, sound levels were

measured OK. There was less than half an hour left on the time limit!

The customers were told the that the contract

could now be signed, saving what might been £2 million in

penalties, and everybody left very happy, But Mick and myself, who

had worked our backsides off, were just left standing there. No

pay rise, no bonus, not even a thank you or a couple of bob to have

drink, absolutely zilch. I didn’t ask because I knew what the answer

would be: You get paid, don’t you. This was typical of STC management

at the time.

|

Philip Burgess Sykes

All those who worked with him speak highly of Philip Sykes. First Officer aboard CS Ocean Layer when she caught fire in 1959, he was involved in the cable industry for much of his career. As Jim Jones notes above, Mr Sykes died in 2006. Here David Watson and Jim Jones share their memories of working with Philip Sykes.

David Watson writes:

I worked with Philip Sykes on the Projects side of the company when STC bought out SCL in the 1970s and found him to be a very competent man to work with. He was in charge of the Anzcan project in Noumia during the off-loading of cables from the freighter Brookness and the Cable Venture. I was out there with him and Ron Fox and it was a pleasure to work with people who knew their way around cable.

Jim Jones writes:

I first had contact with Philip (then Mr) Sykes in the late fifties— he knew everything about everything to do with submarine cable. I also knew Ron Fox’s father, Joe Fox. Here’s a short story about Mr Sykes, then working for Submarine Cables/Telcon.

My second London docks job as an apprentice carpenter, working on transferring cable from barge to ship, started at 7 am one morning. I was ready to help transfer timber from a barge onto the ship to build a temporary cable tank, then suddenly I was told not to touch anything by the guy I worked under, George Bray, until further notice; that meant everything, tools, materials etc. The reason was that the docks were starting to close down. The Dockers Union had decided to take over all work carried out in the docks, and if we carried on we could start a national dock strike.

The company always used their own labour to transfer cable in the UK and didn’t want the Dockers to take over. I hung around all day with carpenters and cable hands, then late in the afternoon we got the OK to start. I asked George Bray, how did they get round that?

I was told that when the Dockers Union told the company they were taking the job over, the company caved in. The company’s representative, Phil Sykes, told the Dockers that as long as the Dockers could insure the cable the company would stand back. Of course the company knew that the Dockers Union wouldn’t be able to get the cable insured, so just sat back and waited.

Late in the afternoon, as the Dockers Union couldn’t get the cable insured they backed down, then we got the OK to carry on. Jack Dash, then the Dockers Union leader, was involved in the negotiations. He was the guy who at the click of his fingers could shut the docks down, but dealing with Mr Philip Burgess Sykes must have come to a bit of shock to him.

I thought then that it was a brilliant manoeuvre to put the decision-making back as the Dockers Union responsibility.

Just to sidetrack a bit to when we did hire Dockers—that was when the company were short of cable hands, and they mixed with our own. The company had to hire gangs of fifteen Dockers but only ten would turn up for a shift, so the company paid for five men that weren’t there. The company couldn’t complain as the Dockers Union was so strong; if you did they would “black” the job (as they then called it) and the job was put into dispute and brought to a standstill. No wonder they wanted the docks shut down.

Even in Antwerp in 1981 we had trouble with the Dockers. With the help of the ship’s captain, plus Philip Sykes and myself, we able to stop them closing down the job—see the full story below. At the end of that job I was invited back to the ship for dinner by the captain as a thank-you— nice to be appreciated, and something that STC never managed to do.

When Mr Philip Sykes wanted something, he got it. Personally, work-wise, I gave him the greatest respect and he by his actions had respect for me.

|

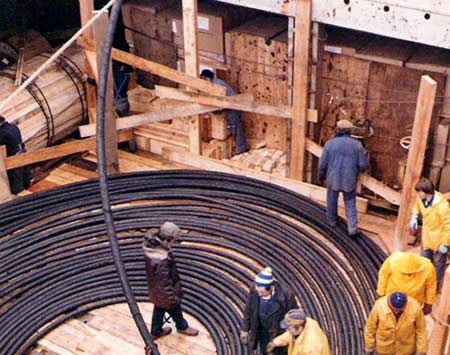

The next group of photos show the unloading

of shore-end armoured black cable from coaster onto freighter in

Antwerp in 1981 (cable from Southampton). The cable was going on to Singapore

to be put in storage for emergencies.

|

|

Wearing a brown coat, and the cheese-cutter

hat that all London Dockers wore before they were closed down, Jim

is the one standing on the eye of the coil doing an on-the-job training

program of how to move cable from one ship to another. |

|

Philip Burgess Sykes is at the right of the group looking down the hatch.

He was First Officer aboard CS Ocean Layer when she caught fire in 1959.

Jim Jones reports that Philip Sykes died in July 2006. |

| These guys had never done a job like

this before, and it’s not as easy as it looks. And I hadn’t done this

type of work for 15 years or more, not since I had worked for Telcon. |

|

|

Jim Jones tells the story that goes with the photos above:

About a month before Christmas 1981 Mr Philip Sykes walked into the STC carpenters’ shop, came up to me, and asked if I’d be willing to go to Antwerp docks to transfer shore end cable from ship to ship. I replied no, for me that was all in the past, but Mr Sykes was dogmatic in what he wanted.

I didn’t tell him that I had an irritable medical problem and would probably let him down while working in Antwerp, so I put up every excuse I could to him not to go—such as I didn’t have a passport; I didn’t want to be away over Christmas because of my young children; and I hadn’t done a dock job for fifteen years since I worked for the Telcon. I also had lots of work on, and site services whom I worked for probably wouldn’t let me go.

But that didn’t put him off.

The next thing I had a phone call from Mr Graham Lawrence (Managing Director), could I go and see him. Wondering what he wanted, and arriving there. I was shown straight in by his secretary and asked to sit down. Then Mr Lawrence explained that Mr Sykes had been to see him, and the company would like me to go to Antwerp. I explained to him that I was past it for doing dock jobs, not telling him the real reason. But after being spoken to like a VIP, and being told that I would be a temporary (supervising only) project manager, I reluctantly gave in. He thanked me and I left.

Later, Mr Sykes turned up in my workshop and said Mr Lawrence had told him I gave in. But I still didn’t have a passport and getting one would take too long for me to go to Antwerp—still trying to find an excuse not go. Mr Sykes told me to go and see Claire, his secretary. When I arrived at her office she told me that I would be picked up by the company car with chauffeur the day after tomorrow and taken to Petty France Passport Office. At the passport office I was told to go to the business passport section, where, to my surprise, the passport was ready, complete with photo.

Back at Greenwich my boss Mr Prendergast came to see me, asking, “Is true you’re going to work for the projects department?” “Yes,” I replied. “Well, nobody has informed site services and you’re not going, we’ve got too much work on.” I told him that was OK with me, I didn’t want go anyway, and he walked out in a huff. I phoned Mr Sykes and explained that my department wouldn’t let me go. Mr Sykes came to the workshop and said, “You’re going.” “What about Mr Prendergast?” I asked. “He’s been spoken to.” And that was that.

As I would be working temporarily for the projects department, I had to sign a contract that I would work for eight hours a day for six days.

The week before Christmas we arrived in Antwerp, and there was a one day’s delay getting to the ship to load cable. Meantime I asked Mr Sykes, “Can these guys we’re hiring speak English?” He replied, “I’m not sure.” If they didn’t, that was going to make it difficult for me, and explaining how build a temporary cable tank in the hold of a ship would be awkward. So I decided at the hotel to do sketches of how to construct a temporary cable tank.

Arriving at the ship I was introduced to the shipwrights who were going to build the cable tank. None could speak English, only Flemish or French, which I couldn’t, so I showed them the sketches, trying to explain how to go about it. After a short while they took the sketches and they were off, me with my fingers crossed and keeping an eye on them.

Within a short time the cable tank was up and ready for the cable to be delivered into. Starting to put the cable in was difficult, as these guys had never transferred shore end cable from ship to ship, so on- the-job training happened. Progress was slow at first, as especially with shore end cable it’s hard work even with experienced cable hands. It went well for three days, even catching up on the delay of one day at the beginning. Then there was sabotage during our rest break in the mess room. One of these guys had knocked out some of the cable tank supporting timbers; we then had to stop the job. Phil Sykes, Harry Stocker and I talked about the problem.

Because the problem would be serious to get over, we came to the conclusion that the hired help done the damage. It was assumed that they wanted to put the cable back in the other ship and start again, trebling their earnings. In fact, it would mean doing the job three times (loading, unloading, and loading again), plus delaying the ship’s sailing time with resulting port costs.

Mr Sykes suggested I repair the damage, as the shipwrights had left the job. I replied that I could probably overcome the problems, but had no tools, plus if I touched it could cause a dispute holding the job up again. The first officer of the ship was then involved, and he said they couldn’t sail, as the cargo had to be secured, and if the cable moved while at sea it might damage other cargo in the ship. To this we all agreed. The First Officer asked could I fix it, and told him too that I had no tools, plus I could create a problem by working on the ship and perhaps causing a dispute.

I explained to the ship’s officer that if I had some tools, plus floor winches, I could pull the cable back into place then replace the shoring which was knocked out by the saboteurs. The ship’s officer decided that with the cable loose like that it was a health and safety issue, the ship’s safety being at risk, thus getting around the possible dispute problem. Within the hour the ship supplied the tools, and, to my surprise, the floor winches.

Harry and myself set up the floor winches and managed to pull the cable back and replace the timber shoring, We were back where we had left off, but lost half a day’s cable loading time. From then on we watched the cable being loaded, along with some of the ship’s crew watching every move the hired Dockers made till they finished.

In the evening I was invited back by the ship’s captain for dinner as a thank you for getting round the sabotage problem, and getting the ship away on time. Appreciation like this was something STC never managed to do.

My actual working hours over the six days were:

One eight-hour day waiting and two eight-hour days loading cable. To get the job back on time: fourth day eighteen hours; fifth and sixth days 36-hour shift right through. Even with all the problems the ship sailed on time. I worked 36 hours above my contracted hours to get the job done, hoping that since I had sorted out the labour problems STC would pay me for those hours

I got back home the day before Christmas Eve, completely worn out after working all those hours. Back at STC Greenwich I went to the personnel department and asked to be paid for the extra hours, explaining that in spite of all the problems we managed to get the ship away on time, saving STC thousands of pounds of costs which would have been incurred by delaying the ship’s sailing. No, they wouldn’t pay. They quoted my contract, and I told them I wouldn’t do it again.

Also on return to the UK Mr Sykes asked me to join the projects department but I turned it down, and said I would do it when required, preferring to stay at Greenwich. I still didn’t want to tell him about my health problem.

|

I went to Antwerp again with Mr Sykes and Harry Stocker the following year, with my contract conditions changed. But there were more problems to solve.

Antwerp Docks, 1982. The coaster arrived from Southampton and tied up alongside. I went down a rope ladder onto the coaster from the freighter that the cable cargo was to go into. The Captain told me they had problems on the voyage, taking on a lot of sea water, as it was a rough trip across the English Channel. The ship also lost some buoyancy coming from sea water into the docks.

The Captain said we were to hold off—the food was all ruined, all their clothes were soaking wet, they needed to shower, etc. After pumping out the sea water they were going into to town to sort out their clothes and restock with provisions, which would take about two days, and we weren’t to take the hatches off till they got back. I asked could we make a start, as Dockers had been hired and the company would have to pay them two days for doing nothing; also the ship would be delayed sailing after loading. “No,” he replied.

Then I asked if he had any beer on board, and he did. “If I could sort something out, would you interested?” I asked him. “I could save you going into town; I’ll let you know soon as I can.” I went back aboard the (British) freighter, found a crew member who looked like he had bit of sway, and told him the situation with the coaster alongside. Could he help if we gave him creates of beer off the coaster? “Hold on,” he replied, and went away. When he came back he told me the coaster’s crew could come aboard, fetch their clothes and the ships laundry would sort that out, plus they could have a shower and clean up, and the freighter would supply bread, bacon, eggs, and butter for a couple of days. (I actually don’t think it was anything to do with the beer, just seamen looking after one another).

I went back to the coaster captain and told him the arrangement, and asked if he was happy with that as long he could supply three crates of beer. To my surprise, he answered “Yes!” And he told me that the hatches could be opened once the sea water had been pumped out. In the meantime the temporary cable tank was being erected in the freighter, ready to receive deep-sea lightweight fibre optic cable from the coaster. At midday the hatches were taken off, and Harry Stocker had already set up the cable running gear ready to bring the cable over. So we only lost half a day instead of what could have been two days. From then on the job went as sweet as a nut—it’s a lot easier loading fibre optic than shore-end cable.

Half way through loading the cable I was leaning over the hatch keeping an eye on things when a leading seaman came and stood alongside, saying he’d never seen this before, loading cable into a ship. I asked him, being nosey, this top part of the hold was empty and what was in the next hold. “Ammunition!” he replied. Blimey, I said, ammunition? It was an ammunition ship. He said it’s OK, you’re safe enough. It was loaded in the UK, where they weren’t allowed to load other cargoes at an ammunitions wharf, and that’s why the cable was being loaded in Antwerp.

On our last day at the five-star hotel (the only perk we got from STC), a Mr Green introduced himself to me. He explained that he had visited both cable loading jobs at Antwerp, last year and this year, and invited me out to dinner to any restaurant I would care to go. Not knowing Antwerp I left the choice to him. Later that day I met up with him at a restaurant opposite the hotel. After we sat down and ordering our meal, he explained that he had a shipping agency at Southend in Essex, and would I like to go and work for him. I asked him what this involved and why he was talking to me.

The job he was proposing would have required travelling around Europe troubleshooting ships, keeping an eye on ships arriving and leaving, plus sorting out loading and unloading cargoes if there were any problems. “Why you are asking me?” He replied that he was impressed with how I sorted out last year’s snags plus this year’s problems with the coaster. “No,” I told him, “I’m afraid I couldn’t do it; I have medical problems and couldn’t be relied on.” He said that this could be covered, plus he offered up to five times my then salary, and he had his own private jet to take me anywhere in Europe from Southend Airport, no waiting at other airports. If my health had been better and I had been fifteen years younger I would have taken him up on it, but reluctantly I declined the offer. Right place wrong time? Bugger, so back to STC Greenwich working as a maintenance carpenter

This trip to Antwerp in 1982 was the last cable job for me with STC, apart from being asked in 1989 to go to Singapore for six months, tied up to a cable depot, which I turned down. In 1989 I was being made redundant as carpenter, so I accepted the money and moved on, as STC was in decline by that time. I ended my working days as a technician for the Electrical Engineering Department of Imperial College London, taking early retirement in 2004 on health grounds.

|

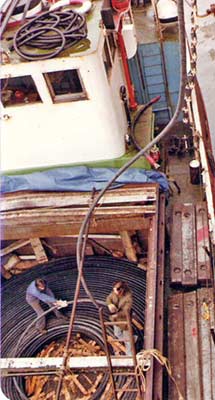

These photos

show the cable loading operation at Antwerp in 1982. This time it’s deep-sea

white fibre optic cable. This type of cable had to be handled delicately

because of its thin covering with no armouring. Soft rubber-soled

boots had to be worn. Value of the cable was around £10,000,000. |

|

| STC men that were on both Antwerp jobs were

Phillip Burgess Sykes (ex CS Ocean Layer), overseer, Harry

Stocker, slingsman, and Jim Jones, carpenter on loan to projects

department of STC. |

|

|

The floor of the tempory tank in a ship’s hold

was called layout, and the uprights were called soldiers. All shoring

from the soldiers was fixed on timber pads wedged against bulkheads

or ribs of the ship or other cargo to spread the weight out, this

doing less damage to the ship when at sea.

Shore end cable is like steel 3-inch hawser;

it always has a tendency to want to unwind, especially when at sea

with the movement of the ship. When moving cable in this manner,

once you start you don’t stop till it’s finished!

Usually three of what they used call cable

gangs, 10 to 15 in each gang, took it in shifts to move cable. |

|

Nearest the camera is a coaster crew

member, then Harry Stocker, STC slingsman, with cable running gear

behind him |

Cable running gear, feeding cable from

coaster to freighter running off ships winches. This running gear,

weighing up to five tons, was brought from Greenwich and was set

up by Harry Stocker, STC slingsman, no easy feat. |

Return to Telcon main page |