|

Sailors have always turned their hand to crafts to while away the long hours at sea, and those working on cableships are no exception. Most of the crafts tend towards nautical themes; carved shells and model ships are typical examples. But James Dooley, who sailed on the British Post Office cableship HMTS Iris (2), worked instead on violins, and made the one shown here on board ship some time in 1941.

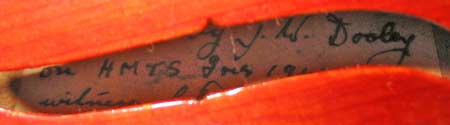

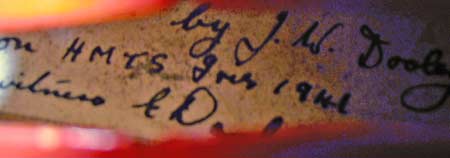

Mat Stephens, the present custodian of the violin, notes that there is a handwritten label visible through one of the F-holes:

Made by J.W. Dooley

on HMTS Iris 1941

witness E Danbury Q.M.4

Dooley was a known violin maker; his entry in Dictionary of Contemporary Violin and Bow Makers by Cyril Woodcock (1965) reads as follows:

DOOLEY, James W.

Born at Castleford, Yorkshire, 1910. Moved to Dover at the age of 15 years and commenced to make violins a year later and has continued ever since despite spells in the Royal Tank Corps and Merchant Navy which he left in 1946...[a few lines regarding violin design]...One violin completed in Glasgow in 1949 is used with great success by a professional player with the B.B.C. Scottish Orchestra, and Mr. Dooley dedicated this instrument to his father. It was made over a considerable period whilst he was still at sea....

James Dooley is also mentioned in Violin Making in Scotland: 1750-1950 by David Rattray (2006), which notes in its entry on Andrew Smillie, violin maker of 368 Western Road in Glasgow:

A regular visitor to the shop was the maker James Dooley (1910-1998), who recalled assessing the projection of Smillie’s instruments from the opposite side of Great Western Road.

The Dictionary of British Violin and Bow Makers by Dennis G. Plowright (1994) also records that Dooley lived in Glasgow in his later years.

Mat Stephens would appreciate hearing from anyone with further information on James Dooley and his service on HMTS Iris (2); please contact Mat through the Atlantic Cable website.

The label inside the F-hole

|

Violin images copyright © 2006 Mat Stephens

In March 2011, Jim Coulson’s daughter Mary sent this photograph (Jim is standing, second from the left):

The caption on the back of the photo reads:

Sing Song in Mess-room

Maestro

Scraper Dooley

Detail of James Dooley |

The photograph is undated, and Jim Coulson’s service records were lost in the fire on CS Ocean Layer in 1959, but Mary notes that it must have been taken on HMTS Iris (2) in the early 1940s as her sister, born in 1943, was named for the ship.

Markings on the back of the photograph refer to the Illustrated, a magazine published by Odhams in London. Mat Stephens has a copy of the May 30, 1942 issue, which features an article on HMTS Iris and includes this photograph. The caption there reads:

A singsong in the forecastle after the day’s work has been finished. Quartermaster J.W. Dooley,—“Scraper” to his friends—leads the singing on one of the violins which he makes as a hobby.

In August 2014, James Dooley’s niece June English sent this reminiscence of her uncle, together with a poem she wrote in his memory:

My name is June English and James Dooley was my uncle. I remember him well.

Near the end of the war he was serving on a cable ship, but was put ashore because he had appendicitis. We had just returned from Castleford, where we were evacuated, and were sat around the wireless listening to the news that his ship had gone down with all hands. You can imagine the weeping and wailing, we thought we’d lost him to the war! Then, without warning, he walked through the door and into our arms. He hadn’t heard about his ship and was really upset.

[Editor's note: The only ship that matches this description is HMTS Alert (2), which like Iris was also owned by the GPO, and was lost in the Channel with all hands in February 1945.]

James Dooley died in 1998, but is still known for the violins he carved. I remember, when I was a small child, my father telling me how he’d found a book for him (he was a rag and bone man at that time) in a house that explained how Stradivarius made his violins and brought it home for Uncle Mick. Many is the time I sat at his feet while he was whittling away.

He was a loving uncle to me; he would walk through the door, pick me up and swing me round. I was proud to walk down the street with him when he came home on leave and I can still hear the delight of the children who ran up behind him shouting, "Touch yer collar, never swallow, never catch a fever," as they jumped up to flick it up in the air.

The war was hard to live through, but we had good times, especially when he came home on leave. Uncle Mick played his violin, Mum played the piano, Gran the saxophone, and my (Step) Grandfather played a tune on upturned glasses.

There’s more to tell of my Uncle Mick’s violins, which became well known. For example, he sold a lot of them to the Philadelphia Orchestra and they were used in performances. He was also well known at Sotheby’s, where he went to value and price violins. He told me a story of how, on one occasion, he went there, by request of management and walked in the front door, where he was turned away, sent to the back door. The story is that Management were furious and insisted he be greeted at the main entrance with full staff support and escorted to the sales room with the dignity that his status as a musician, violin maker deserved.

It wasn’t unusual for a top violinist to bring an instrument to him for repair. One brought hers to him after doing a performance abroad; she sat with him while he took it apart and set it right. When he put it back together he asked her to play it and sat there enthralled - then said, No charge …

Those were the days!

Here is a poem I wrote about his work:

The Violin Maker

For my uncle James Dooley

Year after year he sat cross-legged,

pen-knife in raw-boned sailor’s hands,

(roughened by years of cable laying),

whittling away at the wood, slowly

shaving and shaping a block of pine.

She got the gist: forty one pieces

glued together, book-matched pine [1]

for back and Sycamore to curve

the breast, Canadian Maple bridge -

ready made pegs and catgut strings.

He camped out in the basement, studied

Stradivarius, ‘His Life and Works’.

Using resin from the Tung Tree,

and mineral mixes - high in silica -

he made and exploded varnishes!

She lived with the smell of lacquer,

‘in white violins’ [2] resting on sideboards,

wood shavings and Sea Shanties –

the catacoustics of strained strings

that scratched her home-grown melodies.

Sometimes, when his children called,

he’d swing the baby shoulder high

and dance a jig, till one by one

they all joined in and she would smile,

enjoy the unexpected lull:

it’s time to birth a Dooley Violin,

a masterpiece of hand and eye,

he’s tuning notes, exploring scales,

she’s found the resin for his bow,

hush, the plucking of the strings:

four bird-note song – The Lark Ascending…

Notes:

[1] Matched grain.

[2] The wood of the violin is allowed to rest before varnish is applied.

The poem was published in the collection Sunflower Equations, Hearing Eye, London 2008, and is copyright © June English.

Sadly, June English died in 2018, but an archive of her website is preserved. |