Introduction: On 3 September 1939, shortly after the outbreak of World War II, the Allies cut the German cables from Emden to New York via the Azores and from Emden to Lisbon. In 1944 the American forces needed a secure connection from the USA to the Normandy beachhead, and Addison C. (Cal)

Sheckler relates here a previously undocumented story of how he and his crew accomplished the land operations of this important project to repurpose the Azores cable.

Cal was a Master Sergeant and technical expert on a US Army Signal Corps

team in Normandy following the D-Day invasion of France in June 1944.

M/Sgt Sheckler and his crew established the cable head and cable station

for the former German cable, which had been picked up by CS John W. Mackay and extended to Normandy. The

cable was used for direct and secure transatlantic communication by

the US Armed Forces in France for the duration of the war and after.

Editor’s Note: In December 2023 I received an email from Margaret Watkins, whose father Hubert Mott was one of the enlisted men at the cablehead. She provided details of his life and career as well as photographs of her father, including a variation of Cal Sheckler’s photo of the cable men, but with some of the subjects identified.

As Hubert’s story runs in parallel with Cal Sheckler’s account, I have inserted his text and photos in the appropriate locations below, identified by a red border.

See also Rudy Rudolph’s story of the cablehead after Cal Sheckler and Hubert Mott left in November 1945 along with the rest of the original RM crew. Daniel Crean, who Cal Sheckler mentions as taking on the position of civilian station chief when Cal went home to New York, was still at the cablehead when Rudy arrived in late 1945.

|

History

of the Transatlantic Cable Station "RM" in World War II

by

Addison C. Sheckler |

While it is difficult

to be precise, it would appear that the United States Army’s interest

in a transatlantic cable began in early 1942. This is evidenced by the

earliest date on some of the Western Union Company’s blueprints. It is

obvious from Western Union documents that a concerted and continuous effort

began at this time.

|

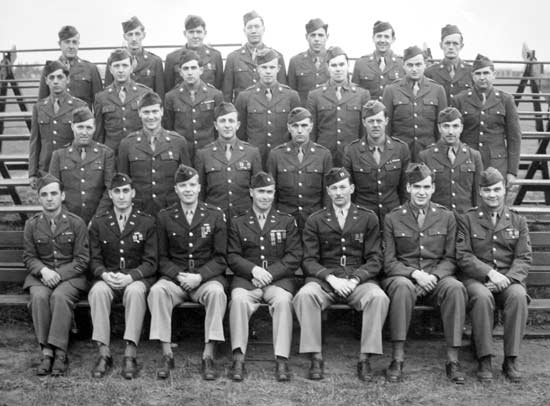

M/Sgt

Sheckler

School Photo, 1943 |

The Army Signal Corps

collected the necessary personnel during 1943 and at least in some of

the cases they were held on "Rations and Quarters" with little

or nothing to do. The author had been ill during the summer and the Army

sent him home for a ninety day "Recuperative Leave". The group

was assembled in New York in January and was assigned to study at the

Western Union Company’s Research Laboratory at corporate headquarters

at 60 Hudson St. The group consisted of eight enlisted men and two Second

Lieutenants.

The course work

was taught by Mr. W.F. Wilder and Mr. Dickey, both of Western Union’s

engineering department. The instruction started with Lord Kelvin’s definitive

treatise on telegraphy. All aspects of ocean cable telegraphy were taught,

from the simple devices like the siphon recorder to the most modern equipment

used on high speed multiplex cables. The work included operation and maintenance

of the various machines which we would use. We were also taught the protocol

necessary to set up and operate a modern cable station.

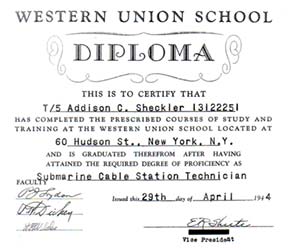

3104th Signal Service Battalion, Headquarters Company,

U.S.

Army Signal Corps photo

[Probably taken at Camp Edison,

Sea Girt, NJ sometime

in the spring of 1944. See also

Hubert Mott's

photo at the

end

of

this page, which was taken at Fort Monmouth, NJ in May 1944]

Digital image of the original courtesy of James G. Foradas, Ph,D.

Site visitor Dave Rothwell Sr. believes that his cousin

“Bud” French

is second from the right in the back row.

If you can provide names or any other information for any of the men

in

this photograph, please email Bill Burns: [email protected] |

This all ended, complete

with a graduation and diplomas at the end of April 1944. We still were

not needed so we marked time, but remained at Western Union. They managed

for us to spend time at the operating sites actually seeing the systems

work. We visited the terminal at Broad St (CD); we visited the cable terminus

at Rockaway Beach (Hammel HM). We visited Commercial Cable’s New York

offices and their terminal at Far Rockaway. We even spent time at RCA’s

telegraphic terminal in New York.

About June 4 we were told that we were

leaving immediately and on June 6, 1944 we were on board the Queen Mary

bound for Europe, but we still did not know anything about our organization.

The names of the people follow:

| Officers: |

|

| Second Lieutenant

Orville Williams |

Second Lieutenant

(Name Unknown) |

| |

|

| Enlisted

Personnel: |

|

| Addison C Sheckler |

Charles Chandler |

| Walter Herman |

Hubert Mott |

| Jerome Saffer |

Edward Walters |

| Isadore Gussow |

Name Unknown* |

| *This is believed to be Gino ("Rick") Riciardelli, according to a June 2018 story on him by Amy Hogan of WICZ-TV in Vestal, NY. |

We arrived in Cheltenham,

England and found that we were part of the 3104th Signal Service Battalion,

which was to supply communications for SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied

Expeditionary Force) and for COM Z (Communication Zone).

Hubert Mott

After joining the Army early in 1944, Hubert Mott attended the Western Union School for work with the Signal Corps, with many of his fellow April 1944 classmates specializing as Submarine Cable Station Technicians. He was then assigned to Company C, 3104th Signal Service Battalion at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where his section was briefly present before leaving for England on 6 June 1944 aboard HMS Queen Mary. |

|

The TO (Table

of Organization) said that we were two cable teams of one officer and

four enlisted men each. In actuality we were a single team and had ten

people because we had to operate a cable station twenty-four hours a day,

seven days a week. About the fifth of July we were moved to Southampton

and on the sixth we arrived on Omaha Beach. We were stationed at Valognes

along with COM Z.

|

Marking

time at Valognes, July 1944 |

Hubert Mott

Upon arrival in Normandy on 21 July 1944 Mott and his unit worked on communications operations. One of their major accomplishments was the construction of a complete 16 kilowatt radioteletypewriter station and cross-Channel radio relay at Valognes for COMZ (Communication Zone) headquarters in only nine days at the start of August 1944. |

Again we waited

because the army had not yet broken out of Normandy. Meanwhile the transport

people were moving a truly immense amount of supplies and storing it in

many depots, which consisted of fields with very large piles of crates.

It is hard to describe the magnitude of these supplies. We marked time

helping out where we could but we were sleeping on the ground and for

three or four weeks ate K rations.

About mid-August

we started to look for our supplies, which consisted of 139 large wooden

crates randomly stored in the aforementioned depots. All of the crates

had a code marking on them and you found them by walking down aisles looking

at each crate. It took about five weeks and we found 138 crates. Fortunately

the 139th crate had paper supplies which could be found elsewhere.

|

138

crates arriving, October 1944.

It took two months to find them. |

I should mention

that during this period the one officer (name unknown) had caused a great

deal of trouble. He then decided that he wanted to go to the front lines

so he could be part of the action. His request for transfer was honored

almost instantly and when he left the enlisted men (and some superior

officers) stood and waved goodbye. This left the team with one officer

and eight men.

|

Cable

head, Urville Hague, Normandy, Aug-Sep 1944 |

About mid September

the cable landing site was identified as the beach at Urville Hague, a

small town about eight miles west of Cherbourg. The lieutenant and the

author of this paper surveyed the site for suitability. The area was a

gigantic mine field and had to be cleared. An Army mine clearing company

came in and removed the following from the area that we would occupy:

35 Mustard Pots

- anti-personnel

51 Teller Mines - anti tanks - 10# TNT

100+ Bouncing Betties - Shrapnel anti-personnel

|

Teller

mine damage, Sep-Oct 1944 |

They missed two mines,

one of which blew up one of our trucks and badly injured the truck driver

who was evacuated to England and then to the United States. The other

mine that they missed, one of our fellows stepped on, but fortunately

it failed to detonate. Needless to say you could not go outside of the

limits of our site. Later many people were killed in this area.

|

Bouncing

Betties, anti-personnel mines, Sep 1944 |

Our time was occupied

in moving our equipment, arranging for buildings to be built, obtaining

diesel generators, and two diesel mechanics etc. The English Army had

established a cable landing about one half-mile west of us on the same

beach and we began to cooperate with each other.

About this time

the army got around to ranking the various personnel. Lt. Williams was

promoted to 1st Lieutenant, Addison Sheckler and Walter Herman were master

sergeants, Jerome Saffer and one other (unknown, but probably Gino ("Rick") Riciardelli; see note above) were Technical sergeants

and the remaining four were staff sergeants.

|

Our

crew plus the British neighbor cable crew, with

Lt. Col. Allen Wharton, War Department, 23 Oct 1944

See below Hubert Mott’s photo from the same session,

which identifies some of the subjects |

3104th Signal Service Battalion personnel at

Cable Station RM, Urville-Hague, France, October 1944

Ken Bowling, Ed[ward] Walters, Cal Sheckler, J[erome] Saffer,

W[alter] Herman, Orville Williams, Hubert Mott (HCM)

Photo from Hubert Mott, courtesy of Margaret Watkins |

On October 20, 1944

the cable ship John W Mackay arrived at Cherbourg and Lt. Williams and

Sergeants Sheckler and Herman went aboard to discuss the cable landing.

The cable was the loaded cable 1 HO from New York to Horta, Azores, and

then on to Emden, Germany. The cable had been cut in the English Channel

at the beginning of the war and the intent was to pick this up and bring

it to shore for our use. The cable was landed on October 23 and the splicing

at sea was completed on October 27. We established communications with

Horta, Azores, by key and siphon recorder.

|

Here

comes the line! |

|

Hauling

in first line |

|

Hauling

in the shore end |

The

shore end landed |

|

S/Sgt

Isadore Gussow,

23 Oct 1944 |

British

cable technician finishing off the cable head |

Hubert Mott

Their crowning achievement, however, was the landing of the transatlantic cable head, designated "RM," seven miles west of Cherbourg on 23 October 1944. Following a month of work, the communications system was placed into operation on 5 December 1944. |

The operations building

was an army pre-Fab and was complete enough for us to go ahead by November

5. The author was the only person on the team with engineering experience,

and Lt. Williams and he were the only ones with electrical experience.

Lt. Williams had been a telephone installer for Illinois Bell. Western

Union’s training had been excellent and each person was given his assignment

for installation and wiring and in one week the station was complete.

However no planning had been done for the power wiring other than to supply

the three Hill diesel generators. These were installed at the same time

as the other work but there was no transformers or power cable available.

We found the transformers someplace and installed them. The British Cable

Station down the beach from us had salvaged about 1,000 feet of heavy

power cable from a German command center also on the beach. We "liberated"

that cable and completed the station. For a short while there were hard

feelings between us and the British soldiers but we all got over it.

|

Installing

three Hill diesel generators, about 1 Nov 1944 |

|

Station

taking shape, early Nov 1944 |

|

|

|

Fueling

up. M/Sgt Sheckler and

diesel mechanic, early Nov 1944 |

Now came the hard

part of getting the station working! We had been trained well but something

had not been taken into consideration. The Horta - Emden cable was special

in that it was inductively loaded. There was no loaded cable available

to splice on and bring ashore so they used a fourteen-mile piece of unloaded

cable. This unfortunately created an impedance mis-match at the splice

and the middle frequencies of the cable signal were reflected back. This

in turn effectively created a hole in the cable’s frequency band-pass

response. We had been trained in cable signal correction but this only

applied to linear corrections. The author was the only one who truly realized

what the problem was and consequently was the one who had to solve it.

We got the system up and sort of operating by November 30, but the error

rate was intolerable. It took two more weeks to find a compromise solution

to the problem but finally on December 13 we were successful. We had lowered

the error rate to about 1 in 10,000 and while we could still see this

the user could not and the station continued at this rate from that time

on. At this time the station was handling military traffic on A and E

channels. C channel was reserved for cable management. Later D channel

was extended to Cable & Wireless in London and B channel was devoted

to the British Foreign Offices Delegation at the organization of the United

Nations. The cable had a capacity of about 350,000 five-letter groups

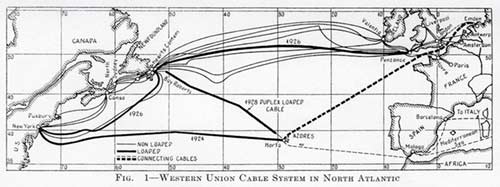

1926 Azores-Emden cable. The inductive loading tape surrounds the conductor. |

A description of

the equipment is in order. Western Union had three special (i.e. loaded)

cables 1 HO (Horta), 4 PZ (Penzance), and 2 HO. I HO was linearly loaded

and operated at 32.5 Hertz. 4Pz was linearly loaded but shorter and operated

at 55 Hertz. 2 Horta was taper loaded and operated duplex at 30 Hertz.

It should be noted that modern cables all operate with single fill-in

i.e. the data rate is twice the bandpass frequency. For more information

the reader is referred to Lord Kelvin’s treatise on Telegraphy.

These special cables

all had special terminal equipment, which was built for the cable when

it was installed. There was very little extra equipment and in our case

there was one duplicate distributor and one duplicate tuning fork (clock)

in New York and these were the units which we used. This left no spares

anywhere. There were no spare amplifiers and the ones in use had been

built by Western Electric in the 1920’s. Consequently Western Union refurbished

the duplicate equipment and designed and built new power supplies and

a new amplifier (which became their new standard). The station consisted

of a 561A amplifier (with cable shaping) and power supplies. This fed

into a five-channel distributor, which was capable of reversing direction

automatically. The distributor was driven by a temperature compensated

tuning fork identical to those in Horta and New York. The time standard

was set by New York; every five letters a time signal was sent and

Horta and our station corrected our time to be correct with New York.

The signal left the distributor or arrived at the distributor through

peripheral signal processing equipment. Signals coming from New York went

to five tape perforators which also printed on the tape. This tape then

went to a tape reader, which sent the signal out on land lines. Incoming

land line signals (which were in Baudot code) went to an electrical/mechanical

translator which converted the Baudot code to cable code which then went

to the distributor and out to New York.

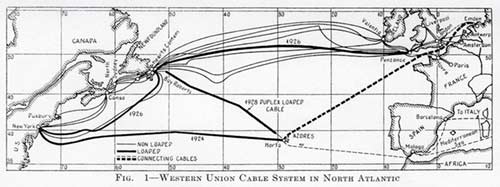

Western Union cable system in North Atlantic,

showing the route of the Azores-Emden cable. |

The station’s code

designation of RM came about in an interesting manner. When we were having

trouble shaping the amplifier we were being sent signals from Horta (HO)

and lots of communications. They addressed us as ARMY. The error rate

was so high that this often came out RM so we adopted that call.

Maintenance procedures

were set up and by the end of December 1944 the station operated without

any difficulty from that time on.

A tape relay station,

JEAC, was appended to the facility and additional personnel were brought

in to operate it. This and subsequent land line operations are covered

in Lt. Williams’ report (appended). The overall manpower eventually rose

to about thirty military personnel, about twenty French civilians, and

forty German prisoners. Interestingly the German prisoners were not guarded

and we had no fence but we had no trouble of any kind. Apparently this

was a safer, more comfortable place than any other they could imagine.

They supplied the facility labor and they made the place into a very good

looking military camp. The author had many conversations with individual

Germans and none of those with whom he spoke wanted to go back to Germany

until the war was over.

Lt. Williams eventually

got bored since there was very little to do and he asked for a transfer.

After him we had a progression of officers who had no knowledge of the

facility and who spent their time making the camp more elaborate. Some

of this is shown in the appended photos.

Unfortunately the

original crew were witnesses to the sinking of a troop ship December 24(?)

just off Cherbourg Harbour. A very large number of people died, perhaps

as many as 1,000.

|

Cable

Station RM, Summer 1945 |

The station operated

with no trouble from that time on. After VE Day (8 May 1945) the 3104th

Signal Service Battalion was sent to the Pacific, but we were left behind

because the station continued. The battalion was on board ship entering

the Suez Canal on VJ Day and they received orders to turn around and go

to New York. They were some of the first people discharged after the war.

We continued on and the army in November 1945 asked the author to stay

on as civilian station chief at an amazingly high salary. The author refused

the position and another man, Daniel Crean, was recruited for the position.

Crean arrived about November 15 and had about two weeks to get acquainted

with the station.

Hubert Mott

While a majority of the unit was designated for service in the Pacific following the German surrender, the men operating RM remained on station in France through at least November of 1945. Mott and the others seem to have returned to the States in December of 1945, with his local paper, the Syracuse Herald-Journal, announcing his honorable discharge from the Fort Dix separation center on 12 January 1946. |

A final anecdote

is in order. Mr. HF Wilder of Western Union, Mr. Breyfogle of London office

Cable & Wireless, and Lt. Col. Allen Wharton of War Department all

were present at the landing of the cable. Mr. Wilder took home a detonator

from a Bouncing Betty mine - a spring snap action device - and when he

got home he got in the habit of snapping this device while reading at

his desk. Suddenly after thousands of snaps the percussion cap exploded

and blew a small hole in his desk top. Fortunately no one was hurt but

he had a permanent memento of the cable station.

|

L to

R: Mr. Breyfogle, M/Sgt Herman,

Mr. Wilder, M/Sgt Sheckler, 23 Oct 1944 |

During 1945 and

1946 Western Union brought together all of the technical documentation

and built new equipment to replace that which we used. The author used

this documentation for his senior thesis at Drexel University. The documentation

still exists.

Technical

history of transatlantic cable head by

Orville H. Williams, 1st Lt. Sig C.

The cable was landed

at Urville-Hague about seven miles west of Cherbourg on the morning of

October 23, 1944. The landing was made from a harbor barge under the direction

of the crew of the cable ship John W. Mackay and Lt. Col. Allen Wharton

of War Department. After the shore end of the cable was landed the cable

ship left to complete the off-shore splices.

On October 27th the

splicing was completed and contact was made with Horta, Azores by siphon

recorder and cable key.

|

|

Sample

of cable used to connect the original German line

to the new cable station in Normandy. As this cable was

not loaded, the impedance mismatch to the existing cable

caused the difficulties in shaping which Cal describes above.

Cable sample courtesy of Cal Sheckler

Photos by Bill Burns, August 2004 |

The operations building

was sufficiently completed on November 5th to start the installation of

equipment and by November 12th the equipment was installed and wired.

The rest of the installation was spent in adjustment of equipment and

shaping of the amplifier. The adjustments of all the equipment was completed

on November 25th; however the amplifier was not yet shaped.

The amplifier shaping

started on November 14th and due to an irregularity in the cable characteristics

was not finished until November 30th.

On November 30th

the final tests were made with Horta, and at 2130 the circuit was extended

to CD in New York. Due to some engineering discrepancies the next few

days were spent aligning the circuit between New York and Urville-Hague.

On December 4th the circuit was connected through to JEJE and JEAR on

A and E cable channels respectively. After a day’s tests the circuit was

put up for traffic and traffic began between WAR and JEJE and WAR and

JEAR on December 5th.

In the period from

December 5th through January 4th 1945, operations were normal with two

exceptions. One of the troubles experienced was with the amplifier shape,

however this was cleared completely on December 13th. The other trouble

in this period was with landlines and this persisted until about February,

when the wire conditions were much improved.

On January 4th a

temporary installation of the tape relay station JEAC was completed after

about two days work. This installation consisted of typing reperforators

and transmitter-distributors terminating the land lines and the same type

of equipment terminating the cable channels. This station, along with

WFQ at New York, allowed full usage of the cable channels and also served

to absorb the time lag between the cable and the landlines.

An alternate traffic

route, terminating at JEAC and JETA, was installed on January 8th.

Work was being done

on a permanent installation of JEAC during this period and on February

2nd the work was completed, and JEAC went into permanent operation.

Another alternate

traffic route was installed on February 28th, terminating in JEAC and

JEVL.

On March 6th, a new

circuit was put into operation on the cable between Cable and Wireless

London and Cable and Wireless Fayal, Azores on the D cable channel.

On March 8th the

alternate route between JEAC and JETA was discontinued.

On March 15th a circuit

between JBJB and JEAC was installed for the purpose of giving JBJB an

alternate route to WAR.

After several tests

a circuit was started up between the British Foreign Office in London

and the British delegation at the San Francisco conference. The circuit

was put through the "B" cable channel for traffic on April 19th,

and continued in service until June 2, 1945.

The full capabilities

at this cable have never been utilized and are approximately as follows;

70,000 groups total for one channel in a twenty four hour period and 350,000

groups total for all five channels in a twenty four hour period.

Orville

H. Williams,

1st Lt. Sig C.

Text and images copyright

© 2004 Addison C Sheckler. Used by permission.

Hubert Mott text and images courtesy of Margaret Watkins, December 2023

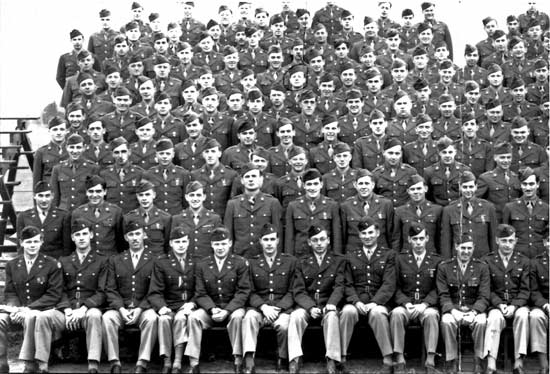

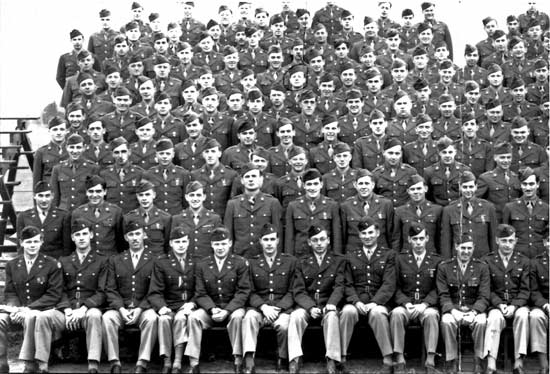

Company C, 3104th Signal Service Battalion

May 1944, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey

Hubert Mott is in the seventh row center, circled

Photo from Hubert Mott, courtesy of Margaret Watkins

If you can provide names or any other information for any of the men

in

this photograph, please email Bill Burns: [email protected] |

Editor’s

Notes: The German cable diverted to Normandy in 1944 was the Azores

- Emden connection to Western Union’s Azores - Newfoundland cable of 1926.

This 1926 cable, identical in construction to the 1924

cable, was linearly loaded.

According to an article in Underseas Cable World, Vol 1, No. 10, April-May 1968, the 1926 cable was once again diverted in 1960, when it was restored to its original path. The German Atlantic Telegraph Company relocated, re-connected, and re-established operation of this cable, which then once again carried telegraph signals from Borkum to Horta, Azores.

For a technical description of the 1928 cable on this same route, which

used taper loading and was the first high-speed duplex long distance cable,

see the 1931 article: The

Newfoundland-Azores High-Speed Duplex Cable.

Postscript: An article in the New York Times, Sunday March 31 1957, is evidence that Cal Sheckler’s painstaking work paid off.

War Prize Put to Work

When the Allies invaded France in 1944, the Army Signal Corps dredged up the cut end of the Emden-Azores cable from the English Channel and led it ashore at Cherbourg, where it was tied in with a military trans-Atlantic telephone and teletype network. It still operates. |

Note, however, that the cable was not used for trans-Atlantic telephone calls in 1944, nor subsequently; this capability was not available in trans-Atlantic cables until TAT-1 in 1956.

Don Morton adds this further note on the later history of station RM:

I was stationed at RM from mid 1951 through December 1952. I was employed as an engineer at Motorola Government Electronics Division in Phoenix, Arizona, when I was drafted in Jan 1951. I had my First Class FCC Phone license and had worked my way through college working in broadcast stations. I had my amateur radio license (W7LBN) which I still have, as well as my degree from Arizona State.

I was sent to basic training for 14 weeks of infantry training and then to Ft. Monmouth New Jersey for assignment in the Signal Corps. I remember the interviewer saying, "You have a ham license so you can copy code?" to which I agreed. His next question was "How would you like to go to France?". I know I happily replied yes, as the alternative was probably Korea and combat areas.

A number of us were sent to school at Western Union’s offices at 60 Hudson Street in New York City for several weeks, then to Rockaway Beach to work on the U.S. end of the cable with Western Union technicians. Then we were sent to France. I think there were six of us—two of us were draftee engineers; another had been working for RCA and I knew him from college and ham radio contacts.

When we arrived at RM, or Cherbourg, the cable had just been cut at sea and the techs on hand were trying to make measurements and determine how far out the cut/break was located. When everyone else went to eat the other engineer and I took a look at the test equipment, made some measurements, calculated a bit and figured out about where the break was located. When the regular personnel came back from eating we gave them our data, they contacted the cable repair ship and they proceed to locate it, pick it up and repair it. Instead of using Morse code to communicate with the ship we used GI field telephones since the break was only 8 or 10 miles off shore.

For routine operation we also put code oscillators in parallel with the telegraph clackers because we were much better at reading Morse from tones than clackers. We later had a break off the Azores that took a while to fix as the cable ship reported it was probably 21,000 feet deep at that point.

We understood at the time that the U.S. had no cable ships and the British did the work at sea for us.

When I was there we were part of 7774 Signal Battalion, headquartered in Germany. Our on-site commanding officer was Maj. Allison D. Melvin, now retired and living in Sierra Vista, Arizona, the last I knew.

I arrived there as a private and left as a Staff Sergeant and went back to work as an Engineer at Motorola, and as a civilian. I learned something about multiplex, saw a lot of equipment that seemed like it should be in a museum but it got the job done and we kept it working. |