|

The cable for this extensive system was manufactured by the India Rubber, Gutta Percha & Telegraph Works Company of Silvertown for the West India and Panama Telegraph Company, a company set up by Sir Charles Tilston Bright with General W.F. Smith and Cyrus Field of the International Ocean Telegraph Company and Matthew Gray of IRGP.

|

|

|

|

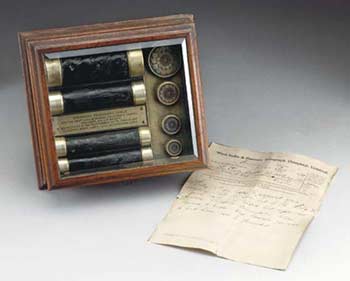

| Cable samples, from shore end to deep sea |

The system eventually interconnected the many islands in the region, with a link to Panama. A new line from Florida to Cuba had earlier been laid by Bright, so the completion of the link from Cuba to Jamaica provided a route from Jamaica to Europe via North America. The cableship used throughout the expedition was the Dacia, assisted by other vessels as needed.

Though laying commenced in 1870 it was 1873 before the network was in full working order. The system comprised:

Santiago de Cuba - Kingston, Jamaica - Colon, Panama

Kingston - San Juan, Puerto Rico - St. Thomas - St. Kitts - Antigua

Guadeloupe - Dominica - Martinique - St. Lucia - St. Vincent - Barbados.

St. Vincent - Grenada - Trinidad - British Guiana.

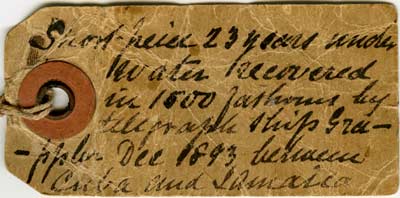

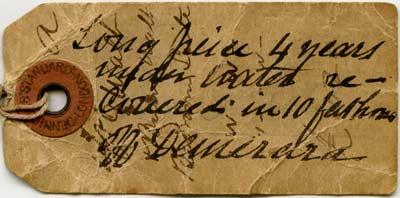

In 1893 CS Grappler recovered two sections of cable, one between Cuba and Jamaica; the other off Demerara, British Guiana. The recovered samples are of identical construction, each being the deep sea section as shown above. A tag accompanying the cable sections gives details of the recovery.

|

“Short piece 23 years under water recovered in 1500 fathoms by telegraph ship Grappler Dec. 1893 between Cuba and Jamaica”

This is from the original 1870 installation between Cuba and Jamaica. |

|

|

“Long piece four years under water recovered in 10 fathoms off Demerara”

This was perhaps from the duplicate cable laid between Trinidad and Demerara in 1890. |

|

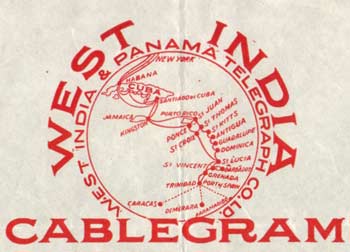

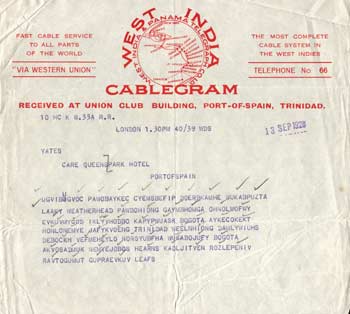

West India & Panama Telegraph Co. Ltd.

Detail of cable route from 1928 cablegram form

|

|

The following account of the manufacture of the cable is taken from the 1898 biography of Sir Charles Bright written by his brother, Edward Brailsford Bright, and his son, Charles Bright.

The type of cable specified by Sir Charles Bright was similar to that which had proved such a success in the heated waters of the Persian Gulf, the patent outer protective wrappings with Bright & Clark's compound being applied; but the copper conductor was stranded instead of segmental, weighing 107 lbs. per mile, the gutta percha weighed 166 lbs. per mile.

There were as many as four types made to suit the various depths. These consisted of very heavy shore ends weighing 16 tons per mile, intermediate of 5 tons per mile, and deep sea of 2½ tons for depths up to 700 fathoms, and for beyond that depth 1 ton 12 cwt. The general character of the main cable was undoubtedly well chosen, as the "open jawed" types adopted for the Atlantic cables of 1865 and 1866 were already showing signs of deterioration.

The whole of the 4,000 and odd miles, weighing nearly 10,000 tons, were made at Silvertown by the India Rubber Company between the latter part of 1869 and the summer of 1870, under the constant supervision of Sir Charles and a highly trained staff, who afterwards went out to assist in the arduous work.

As well as being one of the promoters of the West India and Panama Telegraph Company, Sir Charles Bright was Engineer of the project, and was directly involved in the cable laying. The cable crew had just finished laying the local cables around Cuba, which provided for the first time reliable communication among the major cities of the country. As described in Bright's biography this was celebrated with extensive festivities in Cuba, and the expedition proceeded from there to Jamaica:

The "Cuba" Company's lines being at last brought to a successful issue, the "West India and Panama" series of cables had to be tackled.

Continuing in the route, the first section of this system to be laid was naturally that from Santiago (Cuba) to Holland Bay, on the north-east coast of

Jamaica.

| The above stickiness of the outer compound and a want of lime are matters noted in Sir Charles Bright's diary as entirely novel experiences, such as he had never before met with in laying cables in the Persian Gulf or other tropical climates. |

Whilst all the preceding festivities were going on, preparations were being made for the laying of these future sections by the turning over of great lengths of cable from one tank to another in order to remedy a sticky condition which had proved a great source of trouble in paying out [see sidebar]. Indeed, it was only owing to this being necessary as soon as the Cuban lines were completed, and partly on account of faults in the insulation, that social entertainments as above described could be given time for.

The Cuba- Jamaica cable was laid after some trouble (starting on September 13th), but without any

incident of special or novel interest. The shore end was landed near Plantain Garden Harbour, in Holland Bay [close to Morant Point, an eastern promontory of the island] (from a string of boats), and the final splice effected on September 15th.

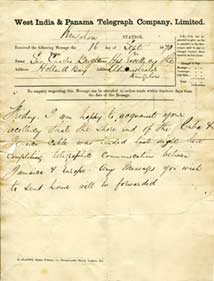

Shown below is a cable sample case for the project, and the telegram Bright sent on 16 September 1870 to "His Excellency the Administrator" in Kingston, Jamaica, from the cable landing site at Holland Bay on Jamaica's eastern shore.

|

|

| Cable sample case and telegram |

West India and Panama Telegraph Company, Limited

Kingston Station

Received the following Message the 16 day of Sept 1870

From Sir Charles Bright, Holland Bay

To His Excellency the Administrator, Kingston

Friday. I am happy to acquaint your Excellency that the shore end of the Cuba & Jamaica cable was landed last night here completing telegraphic communication between Jamaica & Europe. Any messages you wish to send home will be forwarded. |

The following appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette during July, 1870:—

THE WEST INDIAN TELEGRAPH EXPEDITION

ONE of the largest and best equipped telegraph expeditions that ever left these shores will in a few days begin to start on its labours. We say begin to start, for the whole squadron will comprise no fewer than seven large vessels carrying between them more than 4,200 miles of submarine cable. These cables—for as usual now they are of the composite kind, and vary in strength and weight, according as they are to be laid in deep or shallow water—represent the united labours of three companies which have been working together, and a capital of £1,150,000. The West India and Panama Company contributes £650,000 and 2,55o miles of cable, the Cuba Submarine Company 160,000 and 52o miles of cable, and the Panama and South Pacific £320,000 and 1,100 miles of line, making with the land lines no less than 4,700 miles of additional electrical communication, which, when connected with the land lines already existing in North and South America, will literally place every part of that vast continent within a few hours’ communication with London.

The line from Florida to Havana was laid the year before last by Sir Charles Bright. In the attempt it was broken by a fearful storm, and lost in a mile depth of water. It was, however, almost immediately after picked up again with the grappling irons and brought to the surface through a sea which was wildly agitated, and running with a current of still nearly four

knots. This, in the annals of submarine telegraphy, is reckoned as great a feat as the finding of the lost Atlantic cable of 1865. Since then the Cuba cable, as it is called, has worked admirably,

messages having actually been sent from the London Stock Exchange to Havana and answers received in three hours. This has naturally led

the other West Indian islands to seek similar facilities for trade.

Accordingly, the lines now to be laid will, as we have said, connect the islands with North America, and thence with Europe, while on the south communication will be afforded to the east and west coasts of South America. From Florida to Havana the cable is already laid, and from Havana across Cuba there are two rows of land lines to the port of Cienfugos. Here it is proposed to commence operations, carrying

a submarine line along the coast of Cuba from Cienfugos to Santiago, the second great city of the island. From Santiago it passes under the sea at a very uniform depth of about 700 fathoms to

Jamaica, landing somewhere in the neighbourhood of Morant's Bay, whence the land lines take it across the neck of the island to Kingston.

At Kingston the submarine line branches off in two directions. One goes due south under the Caribbean Sea to Aspinwall, where it joins the South Pacific lines, which pass down the south-east coast of America to Valparaiso. The other branch from Kingston goes east and then south, passing south of Hayti to Porto Rico, thence to St. Thomas, St. Kitts, Antigua, Dominica, Barbadoes, Tobago, and Trinidad [Note 1].

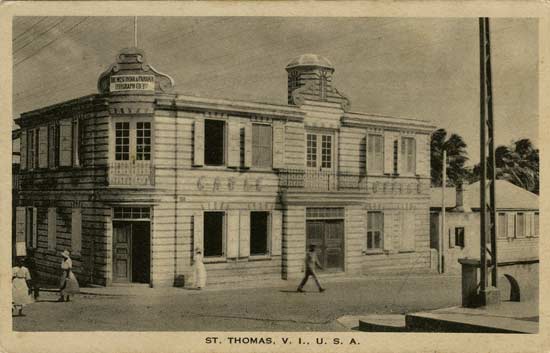

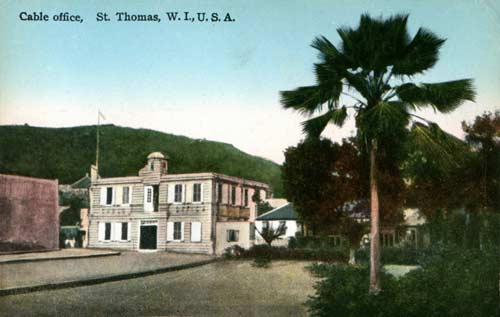

The West India & Panama Telegraph Co. Ltd. [click for detail of sign]

Cable Office,

St. Thomas, V.I., U.S.A.

Date circa 1910-1920

Thanks to site visitor Lise Pyles for her

very kind donation of this postcard |

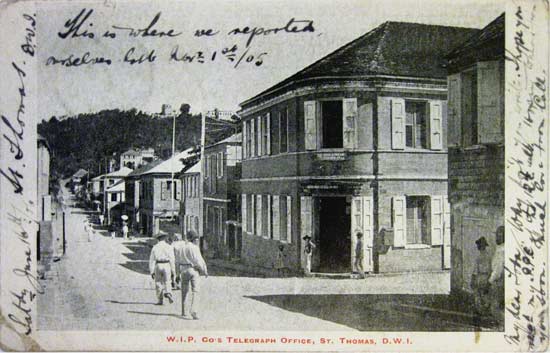

The West India & Panama Telegraph Co. Ltd. Cable Office,

St. Thomas. Postcard dated 1905.

Ship's engineer Collan Bawden Brett served on CS Henry Holmes in the early 1900s, and his granddaughter Kate Brett has kindly provided some information on his service, along with postcards he sent while on cable duty for the West India and Panama Telegraph Company. See the Henry Holmes page linked above for more of his postcards. |

From Trinidad it will pass by cable across the mouths of the Orinoco to Georgetown, thence by land lines to Cayenne, and so on eventually by further land lines across Brazil to Rio and Monte Video. In fact, by these lines all South America and the West Indies will be as easy of access for messages from Europe and India as New York and Boston are now. When the scheme was first announced all the islands were most anxious to join it, and those which have joined it give subsidies to the company amounting to about £20,000 a year for ten years.

[Note 1]

These plans ultimately received modification as regards these sections connecting the Windward Islands by the cable being landed at Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Barbadoes, Granada, and Trinidad. At first, some of the French colonies stood out owing to the promoters of a French company influencing the officials; but eventually—the latter scheme not being realised at the time—they were included

in the West India and Panama Company's system. |

The submarine cables which have been made are among the most perfect of their kind. They have all been manufactured at the Silvertown factory of the India Rubber, Gutta Percha, and Telegraph Works Company at a rate which, considering their high testing excellence, is really remarkable. The copper conductor of seven wires and the insulation of gutta percha is uniform throughout, the former weighing 107 lb. to the mile, and the latter 166 lb. The actual strength of the outer covering of the cable differs very materially. Thus the shore ends at landing-places where the water is shallow and the surf high—and there are more than forty of such places—are of the most massive description, weighing sixteen tons to the mile. The powerful outer wires are thickly coated with Bright and Clark's compound of silica and tar, which effectually shields it from the attacks of the much dreaded teredo.

The next portion of the cable is called intermediate, as resting in neither deep nor shallow water. It weighs five tons to the mile, and for its weight is unusually strong, the wires being of soft steel. For 600 and 70o fathoms the Cuba pattern is adopted, weighing two-and-a-half tons to the mile; the deep-sea lengths weigh 32 cwt. to the mile. The proximate value of these weights as regards strength may be judged by the fact that the first Atlantic cable weighed only one ton per mile throughout its length.

The cables have been manufactured under a guarantee that their insulation should never be less than 250,000,000 units when tested in water at a temperature of seventy-five degrees. It is easy to explain what this degree of excellence means. The electric current when sent through a cable is always trying to escape back to its source by the shortest passage—in other words, to find a flaw in the insulation and get out. In exact proportion as the cable is well insulated, so will be the resistance of the current to entering the wire. This amount of resistance is easily tested by the galvanometer, and is counted in millions of units. If a cable which ought to give 100,000,000 of units resistance is found on testing to give only 50,00,000, then it is evident that the current is going through the cable quicker than it ought, and that instead of all going on to the end it is leaking out from many apertures of escape. Thus cables are always tested by the resistance which their insulation offers to the current, and the greater their resistance the more perfect their insulation will be. T he West India cables have been guaranteed to give 250,000,000 units, but as a fact some portions have given 500,000,0o, and this in water at so high a temperature as seventy-five degrees.

The whole expedition is under the sole charge of the chief engineer and electrician, Sir Charles Bright. He takes with him an able staff

of assistants, both as electricians and practised cable layers. The whole work of coupling up the West India islands with Europe and North and South America will, it is expected, be complete by the end of the year.

Another account of the laying of these cables was published in The Science Record for 1873.

THE WEST-INDIA AND PANAMA TELEGRAPH.

The completion of the West-India and Panama Telegraphs, which was commenced by Sir Charles Bright in 1870, brings the West-Indies, Central and South-America into telegraphic connection with the United States, and, through them, with all countries where telegraphic systems are in existence.

The cable sent out for this arduous undertaking was 3600 miles in length, weighing upward of 8500 tons, and was divided between seven large vessels, and the magnitude of the enterprise, which included the laying of sixteen separate cables under greatly varying depths and conditions, and in several cases during rough weather, is unequaled in the annals of telegraphy.

Many difficulties had to be overcome, especially in laying the shore ends, and providing land lines through dense forests, while the deleterious nature of the climate led to a loss of a number of the staff.

Owing to the irregular character of the bottom, varying from two to upward of 2000 fathoms, four types of cable had to be employed, the first or shore end, weighing sixteen tons to the mile, and the other respectively five tons, 2½, and 1¾, the last being covered with galvanized homogeneous iron wire akin to steel. The shore end cable has two massive coverings of galvanized iron wire laid spirally in opposite directicns, and all the kinds of cable are further covered with two servings of yarn and Bright and Clarke's compound as a protection against the teredo navalis and other marine insects.

The cables unite Havana at one end of Cuba with Santiago, and Santiago with Jamaica, whence they extend on the one hand to Colon, and on the other to Demerara, linking up Porto Rico, St. Thomas, St. Kitts, Antigua, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Barbadoes, Grenada, and Trinidad.

Cable office, St. Thomas, W.I., U.S.A. |

Starting from Havana, which was previously in connection with Florida, the line passes across the Island of Cuba to Batabano, where the submarine system commences. From this point, for about 100 miles, the cable is laid along a tortuous course in very shallow water, passing between rocky islets and coral reefs, and the coast being imperfectly surveyed previously, it was necessary to make a most careful study of the bottom, and to sound over the whole of the route to find a soft and safe bed for the cable. The type of cable used on this section being of the heavy class, a great deal of manual labor was needed, and it was also requisite to ernploy a number of small vessels of light draught.

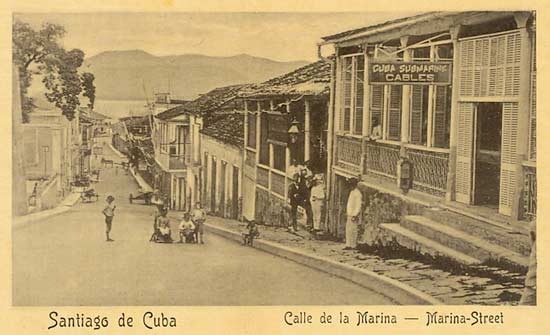

Cable office at Santiago de Cuba |

After passing Cienfuegos the line was laid in deep water along the Cuban coast to Santiago, and the cable was landed amid much rejoicing. The next section laid was to Jamaica, landing it at Plantation Garden River, a work of great difficulty. The west length commenced was that between Jamaica and Colon, where there is a land telegraph across the Isthmus of Panama. The line is one of great importance, and as the traffic and mails from the whole of the western coasts and South-America and the central states, comprising Peru, Chili, Colombia, Venezuela, Costa Rica, &c., concentrates at Panama.

Shortly after the expedition started from Colon northward, yellow fever broke out on board the Dacia; three of the cable men were buried at sea, and many others were on the sick-list. The weather became bad, preventing observations, when, about 300 miles from Colon, a fault was discovered a short distance from the ship, and in endeavoring to pick it up an accident happened, and the end of the cable was lost. Rough weather followed, and interfered with grappling observations. Upon the return of the Dacia to Kingston a number of the cable staff died from yellow fever, and many others had to be invalided home; and as it was in a bad season of the year for grappling work, it was decided to go on with eastern sections, and then return to the Colon line.

The next length completed was between the islands of St. Thomas and Porto Rico, and in succession the rest of the lengths were laid down to Demerara, where, owing to the shallowness of the approach and the liability to ships anchoring over the route, the unusual length of 35 miles of the heavy shore-end cable was submerged, partly from schooners, as the steamer's draught was too great to allow her to approach within 10 miles of landing-place.

The cable which had been lost between Colon and Jamaica was picked up by Sir Charles Bright on December 11th, 1872, from a depth of 1400 fathoms, in latitude 13.58, longitude 7.82. It was then joined up to Jamaica, and the whole of the lines are now in working order.

|