Introduction: John Philip Edwin Crookes (1846-1867), Philip as he was called, came from a large family. His older brother was the renowned chemist William Crookes (later Sir William).

Philip Crookes evidently became involved in the cable industry at an early age. He was an assistant to Charles Bright on the cable to India in 1864 (in charge of cable testing on the Cospatrick) when he was 17 years old, and worked with Latimer Clark monitoring signals at Valentia after the successful laying of the 1866 Atlantic Cable.

Crookes was one of the India-Rubber and Gutta Percha Telegraph Company’s engineers on the ill-fated 1867 Florida-Cuba cable expedition, sailing on CS Narva. While on this ship, which sailed from England for Havana on 28 June 1867, Philip wrote letters home to his family, a number of which include details of the technical aspects of the cable laying and are reproduced below. His last letter from the Narva was dated September 13th: “Rather tired,” and Philip Crookes died of yellow fever on 22 September 1867. He was buried at sea, and is commemorated on the family memorial stone at Brompton Cemetery.

William Crookes believed that his brother’s death was the result of negligence by Frederick C. Webb, who was in charge of the expedition, and demanded an inquiry. After Crookes circulated his complaint to family members, the management of the IRGP, and the ship’s crew, Webb sued him for libel in December 1867. The case went to court, but Crookes eventually apologized and the action was dismissed after he paid a small fine.

A book of Philip’s letters was published in 1868: “Edited and set in type in affectionate respect for his memory by his brother William Crookes”

In Memoriam.

The Last Letters

of

John Philip Edwin Crookes,

Ad Plures Abiit Sept. 22, 1867, Aetat 21.

Sic Itur Ad Astra.

The book was dedicated by William Crookes to Philip’s “Beloved and Honoured Parents."

Thanks are due to the Library of the Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia, for providing copies of the sections of the book dealing with the cable laying. |

| --Bill Burns |

Background to the expedition, by Bill Glover:

THE INTERNATIONAL

OCEAN TELEGRAPH COMPANY

Captain James A. Scrymser applied to the Florida State

Legislature for the rights to land a cable at Punta Rassa; this was granted

for a period of twenty years. At the same time General William F. Smith

applied to the Cuban Government for similar cable landing rights in Cuba;

this was granted for a period of forty years.

The success of these two

applications led to the formation of the International Ocean Telegraph

Company to lay a cable from Punta Rassa via Key West to Cuba. An Act of Congress passed on 5 May 1866 granted the company exclusive

rights to operate all Cuban traffic for a period of fourteen years. At

the same time exclusive rights to operate a private landline between Punta

Rassa and Lake City was also granted. At Lake City the line linked with

Western Union’s network.

A survey of the route was carried out by the United

States Coastal Survey and cable was ordered from the India Rubber, Gutta

Percha and Telegraph Works Company for the two sections of the run. The steamer Narva was chartered from Norwood and Company, and fitted out for cable

laying with equipment designed by Mr. F.C. Webb, engineer for the India Rubber company, and made in New York.

Assistance in the laying at Cuba and Florida was give by a variety of local ships.

The Cuban Submarine Cable

The Times of 27 June 1867 announced the beginning of the expedition:

The steamship Narva, chartered by the India-rubber Gutta-percha and Telegraph Works Company (Limited), leaves Greenhithe to-morrow for

Havannah, having on board 240 miles of submarine

telegraph cable to be laid between Havannah and

Key West (Florida), and between Key West and

Cape Romano (Coast of Florida), thereby placing

the island of Cuba in telegraphic communication

with England and the continent of Europe. Tho

expedition is in charge of Mr. F.C. Webb, civil

engineer, on the part of the Indiarubber, Gutta-percha and Telegraph Works Company, who contracted to make and lay the cable for the International Ocean Telegraph Company of New York.

The New York Times of 12 August 1867 gave a more detailed description of the construction of the cable:

The cable was made by the India-Rubber and Gutta Percha Telegraph Company of London. The Company guarantees the working of the cable for fifteen days, its qualities being considered superior to that of any other submarine cable laid hitherto, experience having furnished many valuable improvements. The cable is composed of seven copper wires, covered with three coats of India-rubber, which are again covered with hemp, the whole being coated with galvanized iron wire coated with zinc. The shore end of the Cable is two inches in thickness, weighing at the rate of two tons per mile, laid to a depth of 150 fathoms; connected with this piece, which is one and a half mile long, is a medium-sized cable an inch and two lines in thickness, fourteen miles in length, weighing one and three-quarters of a ton per mile, and sunk to the depth of 200 fathoms. The same proportions are observed on both ends of the Cable, the centre Cable being thinner, having a diameter of ten lines, weighing one and a quarter ton per mile, and submerged to a depth of 400 fathoms. The communication from Key West to Punta Rosa, through the Florida Bay, is by another cable 133 miles long, nine lines in thickness, weighing three-quarters of a ton per mile. The entire submerged length of the cable is 191 miles.

Assistance in the laying at Cuba and Florida was give by a variety of local ships.

The letters of Philip Crookes

As described by The Times, the cable voyage began on 28 June 1867. CS Narva sailed to Havana via the Azores, Porto Rico, Jamaica, and Grand Cayman, and touched briefly at Cuba on July 26th. In his second and third letters home, both posted from Havana on that date, Philip wrote: “Yellow fever very bad.”

After a brief stop at Havana, the ship sailed on to Florida, reaching Key West on July 27th. On Saturday August 3rd work commenced at Key West with the laying of the first mile of shore-end cable. Philip reported the events in a letter from Key West to his sister Jane, dated August 11th:

Well, on Saturday morning, Aug. 3rd, we steamed out of Key West, accompanied by a Spanish frigate, the “Francisco de Assis,” an American gunboat, the “Tahoma,” and a little coasting steamer, the “Fountain.” We went to the south side of the island, coiled a mile of cable on a barge, and towed the barge ashore, paying out the cable as we went; this took rather a long time, as we had to do everything ourselves. Although the other ships were there to render us assistance, yet we could not even get a boat out of any of them. When the end was ashore, we led it up to a tent that was erected on the beach, and left Donovan there to make the different connections I might require.

The next day, Sunday August 4th, the Narva continued laying the remainder of the shore-end cable, paying out 20½ miles and buoying the end. Crookes had left his colleague, Donovan, at Key West, and they maintained communication through the cable while it was being laid.

On Sunday morning we were all up by 5 a.m., and began paying out the cable. I was, of course, in the testing-room taking constant tests all the time, but I hear everything went quite smoothly on deck. We finished laying the shore end—20½ miles—about 10 o’clock, when we tied a buoy on to the end of the cable and let it sink.

Having completed the Key West shore end, the expedition sent the Fountain back to Key West to pick up Donovan, and that evening set out for Cuba, arriving off Havana about five o’clock in the morning on Monday August 5th. Of the accompanying ships, Francisco de Assis had previously arrived there, and the Tahoma soon followed. The ships remained outside the harbour for fear of yellow fever, and Crookes observed:

A thick dense yellow fog hanging over all the city, not smoke or anything like it, but regular unmistakeable malaria. The sun shone through this fog on to the white houses, and lighted them up with a dull lurid glare, making the place exactly correspond to one’s ideas of Pandemonium steeped in burning brimstone. To add to the effect, the pilot we had on board was strikingly like Gustave Doré’s pictures of Satan. As before, all this appearance vanished about 9 o’clock, and the air and sky were of an Italian clearness for the remainder of the day.

After taking on supplies at Havana, the Narva proceeded to Chorrerra, about four miles west along the coast, where the Cuban shore end was to be landed. There they were assisted by the Spaniards, and the end was soon ashore. The agent there, Signor Arantave, had prepared the cable hut, and, as often happened with cable landings, the local officials organized a party:

This was a very little building, about 6 feet square, but they had prepared marble slabs for the instruments to stand on, with apertures of the right size for the cable to pass through, and a bright brass collar which was to be fastened round the end of the cable to make it look neat and tidy. I have no doubt but that they would have had all the iron wires brightly polished, as in the specimens of cables that are prepared. The poor man, Signor Arantave, seemed dreadfully disappointed when we stripped all the iron wires off and led simply the gutta percha core through all his beautiful preparations, which, of course, would not fit it at all.

We found a brilliant company assembled to see the end landed. There was the Captain-General of the island, who has absolute authority, subject only to the Home Government. He is said to be the ugliest man in Cuba, and he certainly is hideous. Then there were lots of ladies on horseback and foot with low evening dresses, mantillas, and fans, no bonnets or hats; all sorts of vehicles, from the volante to the fly; the houses decorated with flags of all nations, and sumptuous refreshments laid out on tables, said to be provided gratis, but I could not quite ascertain how that was; in fact it was altogether a very gay spectacle, having a sort of resemblance to the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, in which we, however, were the heroes.

On the evening of the next day, Tuesday August 6th, paying out of the main run of the cable began. Donovan again remained on shore while Crookes manned the testing room on board ship. The laying continued all night, but at nine o’clock the following morning, August 7th, the Narva was in a thick fog, and the crew did not know where they were. When the fog lifted they found that they had been carried far off course by a current and were running short of cable.

About one o’clock it cleared a little, and we found to our dismay that we had been carried about twenty miles to the eastward by a current. There was no help for it but to join on some more cable, and make for the buoy, which we reached about four p.m.

Their misfortunes continued; while attempting to recover the buoyed cable they lost the end of the cable they had just laid, then the weather turned bad and they had to run in to Key West for shelter.

Now came the ticklish part. We had to get the cable forward over the bows, pick some up till we got to the buoy, and then haul the cable previously laid up from the bottom, and join the two together. All went well for a time, but at last, in picking up some of the cable (some of that we had had to add on, which was smaller than the other), it broke, and went to the bottom, fortunately only 120 fathoms in depth.

This put a stopper on our proceedings for the time. The next day we commenced grappling for it; but it came on to blow hard, and the sea got so high that we had to leave off.

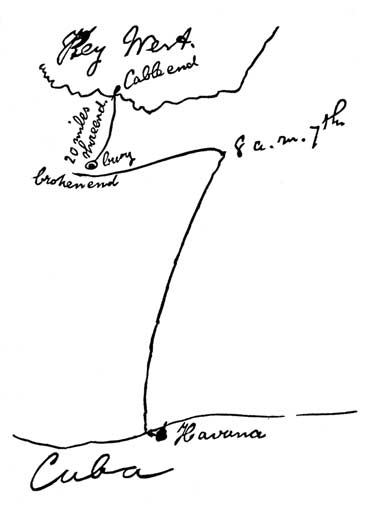

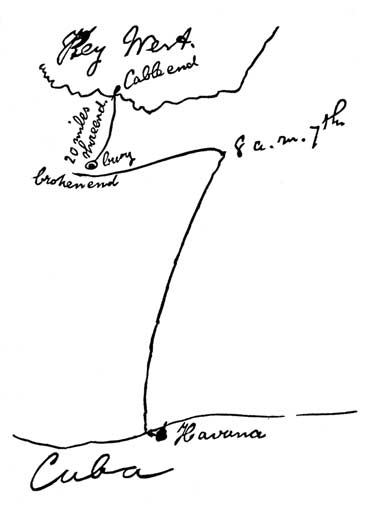

Philip’s sketch map shows the location of these unfortunate incidents.

The Course of the Narva |

Philip’s next letter was written to his mother from “somewhere near Punta Rassa, west coast of Florida” on August 29th and September 1st, and he describes how the expedition continued.

We left Key West on the Wednesday morning, Aug. 14th, and commenced operations again. At first we had no luck, kept breaking grapnels against coral rocks without touching the cable. We began to get very dispirited, and the general feeling in the ship seemed to be that we should not get it at all. On Saturday morning we got a bite, and hauled up carefully. The cable appeared, and everyone set up a shout of delight at the sight. Imagine our sensations when we found it was the wrong cable, viz., that piece going to Key West, which we had laid first and buoyed. There was nothing for it but to let it down again carefully and try for the other one. Our perseverance was soon rewarded.

The same night, Saturday, Aug. 17th, we hooked something again, hauled up the grapnel, and found this time that we had got the right cable. There was no shouting, however; the disappointment of the morning was still too fresh in our recollections, and we feared even now that something might go wrong. We tied a rope to the cable with a buoy on the end, and let it down again till the next morning. At daylight, next day (Sunday), we pulled it up again, cut it, and signalled to Donovan at Havana. For half an hour there was no answer, but then he answered, and we knew all was right.

The cable from Key West to Cuba was now completed, and the ship returned to Key West for a few days, sailing again on the night of Wednesday August 21st for Havana, where Donovan was waiting. Arriving the next morning, they checked the cable landing site at Chorrera then returned to Havana, where they spent the rest of the day sightseeing and shopping for cigars and souvenirs.

The next task was to lay the cable from Punta Rassa to join the Havana cable at Key West, so they set sail again for Florida on August 22nd. Arriving off Punta Rassa on the 24th they made arrangements to land the shore end there.

We got there last Saturday, August 24th, and anchored about 6 miles from the shore, the water being too shallow to go nearer in. On Sunday we had a mile of cable coiled into a little boat, and took it ashore to lay it from the shore, but fortunately met with a little cattle steamer, the “Emily,” of New Orleans, which we hired to lay the shore end from. On Monday morning we coiled 8 miles of cable into her, and took her ashore, intending to start the same evening, but a squall coming on prevented us, so we all slept ashore that night in the telegraph house, which is the only building within thirty miles of the place.

The next morning we started at daybreak, and payed out the cable all right till we got to the ship, when we had two miles over, which we coiled on board again.

There was bad news on board ship; one man had died of yellow fever early that morning, and two more were seriously ill, one dying after a few hours and the other two days later. The cable laying continued at noon the next day, Wednesday August 28th, but a fault was soon found.

The next day (yesterday) we made a start about noon, but immediately we started I saw there was a fault in the cable, and we had to stop and pick up nearly a mile. We took it in, and in the evening I cut out the fault, which was a place that had got very hot in the sun, and the copper wire had come through the gutta percha. We made that all right, but it took us another day; and last night our remaining patient, the cook’s lad, died, and was buried ashore with his messmates.

It was now Philip’s 21st birthday, Thursday August 29th 1867.

At present we are paying out cable and going to Key West, at about 5 miles an hour; we expect to arrive there to-morrow morning, and take that and Saturday to land the shore end, when, unless anything goes wrong, which is not likely, our work will be finished.

I have now to keep a continual look out on the cable to see no fault occurs, or stop the ship should one happen. As there is no one to relieve me, I shall have to keep up all night, so you may think I shall not be sorry when it is over. I will add some more before sending this. For the present, good-bye.

The Narva arrived off Key West on August 30th and prepared to land the end of the cable. Philip concluded the letter to his mother on Saturday September 1st.

We have got here all right, having so far got over our work very satisfactorily. On Friday morning we had laid the cable to about 7 miles from Key West, and the water being too shallow for the ship to go any further, we came round here to the harbour to coil the remaining cable into boats before landing the end, which we hope to do now in one or two days.

Philip began a long and detailed letter recapitulating all the events of the voyage to his brother William on September 8th, finishing it on the 10th. From this letter we pick up his account of the concluding days of the cable laying, expanding on his previous description of the events of Friday August 30th.

(A)bout noon on Friday we got about 7½ miles from Key West. We stopped here, intending to go on with the barge, but a squall coming on obliged us to cut and buoy the cable. We stopped about there all Saturday, during which I was testing all the fragments of cable we had left, preparatory to having them all joined into one length. I had no less than three faults to cut out.

On Monday and Tuesday last we joined all our cable together, and finding it barely sufficient, sent for some more from Havana, which the American Company had fortunately had there for the land line from there to Chorrera. On Wednesday we took the barge with the cable on out to the buoy, made the splice with the cable, and got three boats lent us from the “Lenapee,” an American gun-boat, which had replaced the “Tahoma.”

Progress on laying this last section was very slow, the shallow water causing the boats to frequently run aground, and when the cable ran out about a mile from shore the cable crew retreated to the Narva to await the arrival of the cable from Havana. The Punta Rassa to Key West cable was finally completed on Saturday September 8th.

On Friday the extra cable came from Havana. I tested it and found to my delight that it was in good order, so the following day (Saturday) we put it on the barge, went out again to where we had buoyed the cable before, joined this fresh length on, and went on paying out as before. When the barge would float no more, the men jumped out and hauled the cable ashore, and thus we completed all our work, thank goodness; it has seemed lately as if it would never end. Last night after 8 o’clock the cable earned 550 dollars.

Philip’s last note about the cable is in the section of the letter from Key West dated Sunday September 9th 1867.

There is not much more to relate to-day. I went ashore and took a test of the Florida cable, which tests very well; they are working through them every minute in the day, and if they go on at this rate, the cables will soon pay for themselves.

By now the Narva had lost almost half of its twenty telegraph hands to the fever. In the belief that the center of the infection on the ship was in the cable tanks, which had been inaccessible while loaded with cable, these, along with the rest of the ship, were cleaned and ventilated.

As noted by the New York Times in its article on the cable dated 12 August 1867, the ship had to remain in the area for fifteen days, until it was certain the cable was working properly, and so could not leave Florida. There was a further problem with obtaining coal for the voyage, which would have to be done at Havana. No-one on board was eager to return to Cuba, where the yellow fever was endemic, but they had no alternative.

Philip concluded the letter to his brother on September 10th, and expressed his belief that the worst of the yellow fever was now behind them. Sadly, his optimism about the health of the Narva was short lived; his last letter home was composed on September 12th and 13th at Havana, and he died on board ship of yellow fever on September 22nd 1867. He was buried at sea.

The Submarine Cable—Full Particulars

In its issue of 15 August 1867 the New York Times published a description of the cable laying from Havana to Key West “from our own correspondent,” datelined Havana, Saturday Aug. 10, 1867:

Cuba is already linked to the Continent by the electric wire running through the mighty cable just being laid across the Gulf Stream between here, and Key West, then on to Punta Rasa, on the Florida coast.

Operations were commenced on the morning of Saturday last by the sailing of the Narva together with the United States steamer Tahoma and the Spanish gunboat Francis de Asis, from their moorings at Key West, in the direction planned beforehand. The latter only were detailed to render whatever assistance the former might require during the performance of her task. This, however, was not needed, I am happy to say; the gallant Narva taking the lead, beautifully and nobly did her part, twenty-two and a half miles of cable being immersed during the first hours of that very same day, as follows: First, seven miles of what is termed shore-end cable, weighing eleven tons per mile; then twelve and a half miles, half-size, weighing four tons per mile, and immediately after one mile of deep water line.

As soon as this was accomplished, those on board charged with the control of this gigantic enterprise proceeded to effect a cutting, and after carefully sealing the laid end they moored a cable buoy with a red flag on the spot, placing two others east and west from it, at three miles distance, with blue flags over them, to point out the exact position afterward, when the job of laying the other section starting from the Chowera should be accomplished.

It was Monday the 5th inst., just at daybreak, when the Narva made her appearance off the Morro Castle; the morning was beautiful and balmy, such as you never can see but in this tropical climate, nature itself seemed as if enjoying the triumph of man, and his intellectual powers over barbarism and ignorance. The Narva did not enter our harbor, but hove to, cruising off and on for a while, and coming to anchor shortly after, and at the hour of 10 A.M. steamed to the Chowera, within a mile of the land, where she anchored, making the necessary preparations to splice the shore end with the wire, at 6 P.M., the distance being about seventy miles.

Just at this moment the tug-boat Union, with flying colors, steamed up, having in tow six launches, nicely fitted out with detachments of marines and naval officers, at the same time that the Spanish gunboat which had arrived the night before joined the party, it being superfluous to mention that the United States steamer Tahoma was on the spot. The excitement created here is quite indescribable: every available craft swarmed around the Narva, full of enthusiastic people eager to witness the grand achievement of the age; the city cars and private carriages were crowded from an early hour, carrying all those to the shore who did not relish the excursion by water. Havana en masse seemed eager to see the elephant at that insignificant village, the Chowera, and which henceforth will bear a great renown.

In anticipation, a kind of covered platform had been erected close to the landing point, for the accommodation of the Captain-General, staff, and friends, Mr. A. COLOME, President of the Alianza Point Stock Company and the City Railroad tendered a handsomely fitted car, decorated with flags, to convey the distinguished party, composed in part by Gen. MARIZANO, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Count CANONGO, and many other big bugs who share in the administration of this Island.

When arriving at the scene of operations at 3 P.M., the Narva was ready to detach three boats, one English and two Spanish, to fetch the end of the cable ashore. In the former was the cable, measuring one mile, coiled up. They started, and everything went on well until nearing the shore, one of them struck bottom. Here all nearly jumped into the water, waist deep, to pull it out, but it was found too short. Timely signals to the Narva obviated this difficulty, and after some gallant efforts by our jolly tars, it was successfully run up the mouth of the Almendares River, on whose bank the station is located about 200 yards above its mouth.

Owing to the crooked course of the stream, it could not be spliced at once, but early the next morning it was done, the communication from the shore to the Narva being perfect. Not so vice versa, owing to the connections of one of the apparatuses being foul close to the battery. This was speedily remedied.

Everything ready, the Narva started at 4 P.M. in search of the three buoys placed this side of Key West, in company with the Tahoma and Francisco de Asis. The next day, that is to say at 11:40 A.M., we received the tidings that fifty-eight miles of cable had been immersed. But, alas! how soon our joy was doomed to be marred by overpowering discouragement. On the morning of the 8th the Spanish gunboat steamed into our harbor bearing the saddening intelligence that the cable bad parted from the bows of the Narva at 8:30 the previous evening, when about effecting the junction with the buoyed up cable this side of Key West.

Rumors are contradictory about the accident, but well informed official parties state that it was owing to the commander and pilot on board the Narva, they having refused to accept the Tahoma’s offer to lead her to the buoys. On the 9th the Narva is reported to be about commencing to grapple for the lost end, Gen. SMITH being of opinion that with a clear and smooth day, there is every appearance of success.

Our Havana correspondence is dated Aug. 9 and 10. We have full particulars about the parting of the submarine cable. The Narva is now making the necessary preparations at Key West to grapple for the lost end, and the hopes are that the cable will be found without serious difficulty, the bottom of the sea where the cable was lost being very hard and smooth.

Further news appeared in New York Times on 17 August datelined Baltimore, Friday, Aug. 16:

The steamship Liberty arrived at Quarantine at 6 o’clock this morning with advices from Havana to the 12th inst.

The steamer Emily arrived at Havana on the 12th inst. from Key West and Punta Rasa, Florida. The Narva was still grappling for the cable, but owing to the prevailing storm has not succeeded in finding the lost end. The first pleasant day would enable them to accomplish the desired object.

Finally, in the issue of 25 August 1867, the New York Times reported success:

THE HAVANA CABLE

The United States and Cuba in Telegraphic Communication.

First Congratulations Exchanged Over the Wires.

HAVANA, Wednesday, Aug. 21.

Via Lake City, Fla., Saturday, Aug. 24.

After seven days and nights of hard work the steamer Narva succeeded in grappling the lost cable on Sunday morning. The following telegrams have been exchanged: |

| |

| To His Excellency the Captain-General Manzano: |

| As our facilities of intercourse improve, so may our mutual interests and prosperity increase. |

| (Signed) |

E.O. GWYNN,

Mayor of Key West. |

| |

| (Reply.) |

| To His Honor, E.O. Gwynn, Mayor of Key West: |

| I celebrate this happy event, which, giving us more rapid communication, will powerfully contribute toward the development of our mutual interest and prosperity. |

| (Signed) |

JOAQUIN MANZANO,

Captain-General of Cuba. |

| |

| The first one of these dispatches was sent from Key West at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and delivered to the Captain-General at 8 o’clock in the evening. |

This piece was repeated in the Times the following day, with one additional report from Havana at the end:

The sanitary report of this island for the month of July states that there has been 1,219 cases of yellow fever, of which 226 resulted in death. There were also 134 deaths from the small pox.

Yellow fever is a viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes, but this was not known at the time, and despite the rudimentary precautions taken against mosquitoes because of the annoyance of their bites, once established the disease spread rapidly.

The cable tanks on the Narva would have contained standing water, a fertile breeding ground for mosquitoes, and Philip’s belief that this was the center of infection on the ship was probably well-founded.

As Philip’s last letter to his brother William gives his own complete and detailed account of the laying of the cable, it is transcribed it in full below. I have inserted dates [in brackets] to make the chronology clearer.

Key West, Florida

Sept. 8th, 1867. |

| My Dear WILLIAM, |

I intend in this letter giving you a full account of our operations in laying the cables, and I have delayed writing to you in order that I might be able to give you the complete history of the expedition; you must forgive me if I go over again some of what I have described in my letters to Brook Green, but this will be unavoidable if I wish to make a connected account of it. You of course know that the object has been to connect Cuba with Key West, and Key West with the mainland of Florida, so as to join Cuba on to the American and European system of telegraphic connection. For this purpose two cables were made, one a tolerably heavy one to go between Key West and Cuba, which is the most dangerous part and where the current is very strong, and a much lighter cable to go between Key West and Punta Rassa, the Florida end, where the land wire from New York terminates. The distance from here to Cuba is 88 miles, and 109 miles of cable were provided for that portion; from here to Punta Rassa is 114 miles, and 133 miles of cable were provided, making in all 242 nautical miles of cable. Each cable had some miles made with much thicker iron wires than the rest, for laying near the shore; some 20 miles of this had to be provided for this end of the Cuba cable to bring it into anything like deep water.

You will remember that we first reached Havana on the 26th July, that we got to Key West on the 27th, stopped there a week fitting up (which we might just as well have done in London before starting), and made a beginning on Saturday August 3rd, with the American gunboat “Tahoma,” and the Spanish frigate “Francisco de Assis,” assisting us by calmly looking on. That day we lay at 1½ miles from shore, and had that length of cable coiled on to a barge which three of our boats towed ashore, paying out as it went. This took more time than we expected, as we could get no help from anybody, and by the time we had finished it was dark, so we had to stop there for the night. The next morning [Aug 4th] we deposited Donovan ashore in a tent with the end of the cable, and started paying out at 6 a.m. My business was to take the tests, which were as follows:—Beginning at the hour, for the first ten minutes I had an insulation current on, and took the readings each minute; then for five minutes we spoke to shore: the second and third quarters of the hour were exactly the same, and in the last quarter, instead of speaking to the shore for five minutes, I took the copper-resistance of the cable. Donovan’s duty ashore simply was to insulate the end for the first ten minutes, put it to his speaking-instrument for the next five, and so on, putting it direct to earth for the last five minutes of the hour, while I took the copper-resistance test. All depended on his keeping correct time with me, so as to change the connections just at the right time, as otherwise all the tests would get into confusion. Everything went on all right, and we came to the end of the twenty miles of shore end at about 11 a.m. It was rather hard work for me during the time we were paying out, as I was occupied every moment of the time, and, having no one to relieve me, was unable to go to breakfast till it was all finished. Fortunately, we had a man, named Roe, with us, who had formerly been a telegraph clerk, but had lost his situation through some misconduct, and had joined as a cable-hand in the hopes of getting something better out here. I had him to send and receive messages with the shore, which was some assistance. When we had payed out the twenty miles of shore end we sealed the end up, tied a rope to it with a buoy attached to the other end, and let it sink to the bottom. After this one of the ships went back to Key West to fetch Donovan, and we put down several flag buoys near the cable buoy to mark the spot. When Donovan had come on board we all set off for Havana, the “Francisco de Assis” and the “Tahoma” starting at least two hours before us. The “Francisco” got there first, and entered the harbour. We arrived next [Aug 5th], having passed the “Tahoma” in the night, and anchored just outside in our old position under the Moro; the “Tahoma” lay several miles off to escape the yellow fever. Having got letters and seen one or two people from Havana, we went round to Chorrera, about four miles off, where there is a little bay with a river running into it. We lost no time, but began at once to land the cable, coiling half a mile into two large boats, and having the assistance of the boats and crews of the “Francisco de Assis” and the “Tetuan.” The Spanish certainly behaved very well in the matter of assistance, and ought to have made the Americans ashamed of themselves. Thanks to their assistance, we got the end safely landed by about four in the afternoon [Aug 5th], and fitted up our instruments in the little testing-room they had built for us ashore. I have already mentioned the excitement our proceedings occasioned, and the brilliant assemblage who looked on. Well, when our instruments were arranged, we found that though the shore could speak very well to the ship, the ship was quite unable to reply to the shore. This necessitated my going ashore again, bringing off their instrument, and examining it. I soon found out that one of the contacts had got knocked out of its place, and set it right at once, but Mr. Webb decided that as all our men were knocked up by the day’s work we would not start that night but would wait till the following evening. It was necessary to start in the evening so that we might get to the cable buoy by the morning, and have all the day for making the splice, &c.

The next day [Aug 6th] Mr. Webb and Preece went to Havana to see the ship’s agents, and transact some business, and Donovan and I, after arranging our instruments again, and seeing that they acted right, took a walk into the interior, following the course of the river, and coming to some rather pretty scenery. Cuba is hilly, and looks very well after Key West, which is all as flat as a billiard table. The shore of Chorrera seems all a mass of black mud, chiefly decaying organic matter, and smells horribly; I have some now in a bottle which I collected then; it gives off gas so fast that it has twice blown out the cork. The whole shore seems to be the same; there is hardly any tide, and no current within half a mile of shore. Is it any wonder that the place is unhealthy? The water seems suddenly to change about half a mile from shore; on one side it is a dirty grey colour, on the other, the deep clear blue of the Gulf stream. Well, we started that evening at 4.30 p.m., Aug. 6th, I having to take the same tests as before. We went very slowly at first, increasing our speed gradually. At first the machinery did not work very well, something was wrong with one of the breaks, and the cable would stop for perhaps half a minute, with the strain gradually increasing till it approached the breaking point, when suddenly it would go out with a rush, threatening to carry everything before it, and compelling every one to get out of its way for fear of their lives. This was very unsatisfactory, and about three times an hour Mr. Webb would rush into the testing-room, and cry to me, “Is it all right?” which question I was, fortunately, always able to answer in the affirmative. Another danger was soon added; a number of the iron wires had broken, and several feet of them would untwist, and threaten to stop all the apparatus, when of course the cable must have broken; in the midst of this a squall of wind and rain came on, the sea rose, and the ship became very unsteady. Fortunately, however, this state of things only lasted a couple of hours; by that time we had got over the deepest water, had got the breaks to act properly, and had payed out all the thick cable in which the broken wires occurred; everything then went on smoothly. In the testing-room I kept up the testing uninterruptedly, being startled every now and then by dreadful noises on deck, which put me in a cold perspiration for the safety of the cable; once, too, at the worst time, the spot of light suddenly went off the scale, showing an immense leakage somewhere; I waited a minute or two, doubtful whether or not to stop the ship (which would then have been most dangerous), when the spot reappeared. On afterwards inquiring of Donovan, through the instrument, what he had done, he replied that he had put it to earth by mistake! This sort of things went on all night without my being able to leave for a moment; it was varied occasionally by my blowing up the shore for not keeping better time. Poor Donovan ashore did not pass a very pleasant night either. About nine o’clock I inquired how he was getting on, and he said he had just been eating a mess of fish, potatoes, and garlic, stewed together, which was all he could get for supper. About eleven he got very sick, and was sick all the rest of the night, obliged at the same time to make the different connections at the exact time, it being impossible to trust any of the Spanish operators there to do so for him. What with smoking cigars, drinking coffee, and eating biscuit, I managed to get through the night; fortunately everything went on all right. About 4 o’clock the next morning [Aug 7th] both Donovan and I got awfully sleepy. His time got dreadfully out, I had to correct it every fifteen minutes, and then he would get 3 minutes wrong by the next fifteen minutes. As for me, I found myself dropping off to sleep in the aft of sending a message. By 8 a.m., Aug. 7th, we had paid out all but 8 miles of the Cuba cable; we were in a heavy fog and rain, so that we could scarcely see 100 yards ahead, and we did not know in which direction the buoys lay. Having nothing better to do we stopped still, and waited. About noon it cleared up, and we hailed a vessel and inquired where we were; we found we were 22 miles to the east of the buoy, and only 8 miles of cable left! We did the best we could; we spliced on the Florida cable, and made due west for the buoy, which we reached about 5 p.m. We steamed about a mile past the buoy, shifted the cable to the bow of the vessel, and commenced picking up towards the buoy, intending to get both cables over the bows and make the splice. But, alas! when we were about ¼ mile from the buoy, a broken end came up, and we saw the cable had gone. We lost no time, but put down buoys to mark the place, and commenced grappling. We tried the whole of that week, but did nothing except break two or three grapnels, and on Sunday [Aug 11th] we returned to Key West, with our tails between our legs. It was an unfortunate affair throughout: we had used 16 miles of cable more than we should have done, and we had lost the lot. The most comical thing was our course, which I have drawn on the next page. This was an error in judgment committed by Mr. Webb. He thought from the appearance of the cable at the stern that there was a current taking us to the west, and so, contrary to the advice of the pilot and captain, he had the ship steered to the eastward; the current we afterwards found was also taking us east, and so at 8 a.m., when we stopped, we were in the funny position you see, having contrived to get 20 miles out of our course during a run of 70 miles.

The Course of the Narva |

Well, we stopped in Key West till the following Wednesday [Aug 14th], taking in coals, water, and various supplies, when we left again, and began our old work of grappling, with our old luck. Not one single time did we even hook anything that could be mistaken for the cable, and we were beginning to think that we could not recover it, when on Saturday morning, Aug. 17th, the cry was heard that we had hooked the cable. Every one rushed to the bows, the engine hauled up, the cable appeared, we all raised a shout of exultation, and the moment after, saw from its size that it was the wrong cable, viz., the shore end going to Key West, the end of which was safely buoyed. We let it go and moved to another place to try again. That evening we again hooked a cable, this time the right one, buoyed it, and the next morning hauled it up and made the splice with the shore end. Sunday afternoon we spent in picking up the buoys we had laid down, and on Monday morning [Aug 19th] entered Key West with flying colours.

Key West itself had had a jollification the night before, in which most of the inhabitants got drunk. Unfortunately some of our men followed their example; on Tuesday night we had to send for a guard of soldiers to prevent the men leaving the ship, and getting ashore to get drunk, while of those who contrived to get ashore, two, Wilson, a black man we had brought from England, and Eales our carpenter, slept ashore all night.

The next day, Wednesday, August 21st, we coiled some cable in a barge for the shore part of the other cable, which we left here with one of our hands, named Sparshott, a steady man, whom we could trust to attend to it and keep it always wet. We then started for Havana, where we arrived the following (Thursday) morning [Aug 22nd]. Donovan came on board, looking very well, but saying he was very tired of the Spanish.

We then went ashore, and I saw the town for the first time. It is a good size, very foreign looking, very dirty, very narrow streets, and tall houses with gay coloured flags stretched across from one side to the other to keep the sun off. The shops are all open, no glass appearing to be used; even in private houses the windows are almost all barred across, instead of having glass in them. One square, the Plaza de Armas, looked very pretty, with green shrubs and sparkling fountains. The Captain-General’s palace occupies one side of this, and the remaining sides are filled up with shops, mostly tobacconists. We went in one of these, Henry Clay’s, and made some purchases, while Mr. Webb was transacting business with his agent. In the streets which are sufficiently broad, they have the street railways which were tried in London unsuccessfully some years ago; one of these goes to Chorrera, where the cable landed. We went there in one of the cars, and arranged to leave Roe there in place of Donovan, whom we were going to take on to Punta Rassa. We wanted some one there to represent us during the fifteen days we had guaranteed the cable, for which time of course it was in our hands.

Going on board again we had dinner, and started that evening for Punta Rassa, which we reached on Saturday morning [Aug 24th], but could not approach nearer than six miles, on account of the shallowness of the water. We coiled some cable into a boat, and took it ashore on Sunday to make a beginning, but, fortunately, met a little cattle steamer, which we engaged to lay the shore end for us. On Monday, therefore, we coiled 8 miles of cable on board the “Emily,” and went ashore. We slept ashore Monday night [Aug 26th], in the station there, which is a log house built on piles, and loopholes arranged in the walls for firing at the Indians, who used to be very troublesome about there, but are now pretty nearly exterminated.

The mosquitoes and sand-flies are so bad that the operators there have had a little canvas room built in the house, where they keep the instruments and sleep; by keeping it shut all night they manage to circumvent the brutes. We were not up to that, and attempted to sleep outside, but the sand-flies came in clouds, and prevented any of us from sleeping a wink. About 1 a.m. I could stand it no longer, and so went to the canvas house and looked in. I saw a small space vacant, between the legs of one individual and the head of another, where I coiled myself and contrived to get a couple of hours’ sleep. At 4.30 a.m. [Aug 27th] we got up and went to the “Emily,” which got up steam, and we began paying out the cable. All went well, and by noon we were up to the ship.

You will already have heard the bad news which awaited us. One man had died during the night, another was dying, and a third was very little better. The man that had died was Wilson, the one dying was Eales the carpenter, and the third was the cook’s assistant, a lad of eighteen. While we were making the splice on to the cable on board, and coiling back the surplus cable, a boat was sent ashore to bury Wilson; when it came back it had to go again with Eales; the following day it made a third trip with the cook’s mate.

We decided not to start that night, as the men were knocked up, having had no rest ashore the previous night. The next day [Aug 28th] we made a start, but immediately I perceived a fault in the cable, and we had to stop, pick up again, cut, and make another splice, which used up all that day. It was not until 11.30 a.m. Thursday, Aug. 29th, that we finally started.

That afternoon and night I went through much the same tests as before, except that being in shallow water such unremitting attention was not necessary, and I managed to get away for meals. In the night I got a man to watch the spot of light for an hour while I lay down; at the end of each hour he called me, and I had to get up for ten minutes and speak to the shore, alter the connections, &c. In this way I got a little sleep, and about noon on Friday [Aug 30th] we got about 7½ miles from Key West. We stopped here, intending to go on with the barge, but a squall coming on obliged us to cut and buoy the cable. We stopped about there all Saturday, during which I was testing all the fragments of cable we had left, preparatory to having them all joined into one length. I had no less than three faults to cut out.

Saturday evening [Aug 31st] we went into Key West; there, again, further bad news awaited us. The day before poor Roe, whom we had left at Chorrera, died of yellow fever after three days’ illness; Sparshott also, who had stopped at Key West, was in the Hospital very ill (he died on Monday). On Monday and Tuesday [Sep 3rd] last we joined all our cable together, and finding it barely sufficient, sent for some more from Havana, which the American Company had fortunately had there for the land line from there to Chorrera. On Wednesday [Sep 5th] we took the barge with the cable on out to the buoy, made the splice with the cable, and got three boats lent us from the “Lenapee,” an American gun-boat, which had replaced the “Tahoma.” With their assistance, we towed the barge towards the shore at the rate of about ¼ mile an hour, over water in some places only 3 ft. deep. By night we had made about 2 miles, and had to stop; we all slept on the barge, making ourselves as comfortable as we could under the circumstances; one comfort, there were no mosquitoes, so at all events it was better than Punta Rassa; and the next morning [Sep 6th] started again at 6 o’clock. We went on for an hour, when we stuck hard on a bank, and had to wait till 12 o’clock for high tide to get us off. We then went on as before, occasionally sticking and having to back out and try another channel, until dark, when we had got to about a mile from shore and used up all our cable; we therefore went back to the “Narva” to get a good night’s rest.

One of our cable-hands had been attacked with fever on the barge, and we had sent him to the ship; on getting back we found two more were attacked; all three were taken ashore to the hospital.

On Friday [Sep 7th] the extra cable came from Havana. I tested it and found to my delight that it was in good order, so the following day (Saturday) [Sep 8th] we put it on the barge, went out again to where we had buoyed the cable before, joined this fresh length on, and went on paying out as before. When the barge would float no more, the men jumped out and hauled the cable ashore, and thus we completed all our work, thank goodness; it has seemed lately as if it would never end. Last night after 8 o’clock the cable earned 550 dollars.

We got on board again about 8 o’clock, had dinner; after dinner I sat down in my cabin for a few minutes, during which I went right off to sleep, woke at 4 this morning [Sep 9th], undressed, wound up my watch, turned in and went to sleep again till 9 this morning. I discovered to-day that two others had done just the same,—gone to sleep immediately after dinner, without having time to undress.

We have done nothing to-day but rest. Unfortunately, two more of our men have had to be sent ashore to the hospital.

Sept. 9th, 1867.

There is not much more to relate to-day. I went ashore and took a test of the Florida cable, which tests very well; they are working through them every minute in the day, and if they go on at this rate, the cables will soon pay for themselves.

One of our men died at the hospital this morning, and was buried this afternoon; there are now five left there; of those I am afraid one is sure to die, the rest may recover.

We are having the ship thoroughly cleaned out, especially the tanks. It is a curious fact that, with one exception, the cook’s boy, all the cases of yellow fever we have had have been among the telegraph hands, and none among either the sailors or the firemen. The sickness among the former has been dreadful. Out of nineteen or twenty men we had at first, five are now dead, and five very ill, one almost hopelessly so. This seems to point to the tanks as the main cause of the disease, as the sailors sleep in the forecastle, and our men on the lower deck, just above the tanks. Whatever the cause, it is certainly curious that one body of men should be so severely attacked, and another body on the same ship should completely escape. This makes us hope that, now we have got all the cable out, and can get the tanks and every part of the vessel thoroughly cleaned and ventilated, we shall escape any further sickness. Of course the best thing to do will be to get north, into cold weather, as soon as possible; and I think we shall succeed in getting five days taken off the fifteen, for which we have guaranteed the cable. If we succeed, this will enable us to start for New York next Wednesday week.

Our movements now are very uncertain; in fact, we are in a difficult position, and hardly know what is best to do. We shall want more coals to get to New York, and cannot get them nearer than Havana; but if we go to Havana, they will put us in quarantine at New York. We want to get two barge-loads of coal sent outside the harbour at Havana, so that we may take them on board without entering the port; but there may be some difficulty about getting this done, on account of the uncertainty of the weather just now; and then we fancy they are getting rather frightened here about having the ship in the harbour; and if once we go out, they may refuse to let us in again. If we are forced to enter Havana harbour, we might have to give up the idea of going to New York, on account of the quarantine, and then of course we should take in enough coals for the voyage, and go direct to England. Altogether, it is difficult to say what we shall do. I do not think Mr. Webb would enter Havana if he could help it, as he has a wholesome horror of the place; and certainly no one on board would wish to do so. But we may be compelled to go in; in that case, I have made up my mind to go ashore and live in an hotel while the ship is in the harbour, and I think most of us will do so too, as the harbour is certainly the focus of infection; there is no tide and no current in it, and consequently the water is composed of the accumulated sewage of generations.

It is a great satisfaction to think that we have done all our work here, for lately it has been dragging on to a frightful extent, and every one on board has been getting very sick of it. I fancy if the International Ocean Telegraph Company want any more cables laid in the West Indies (as I believe they do), they will have to choose a better part of the year for doing it, as very few men will be found again to come out here during the summer. It is curious to see how careful the men have suddenly become. During the voyage out no one thought of coming to the doctor; at present if any one feels the least unwell in any way, he immediately comes and reports himself. We have now no difficulty in preventing them from going ashore and getting drunk; they would as soon think of committing suicide.

From all that I can learn, I think we shall arrive in England late in October, or early in November, but, of course, as yet all this is very uncertain. I shall be able to let you know more nearly in my next letter, which I shall probably send from Havana. I don’t know whether I have got all my letters correctly; I think I have only had two, one from Father and Mother, and one from you; you are not behaving so well as you did when I was in India. I got three copies of the Evening Mail, for which I am much obliged; it lets me know a little how things have been going on in England. It is amusing to see in the account of the weather that the temperature in London was 59°. We never have it below 80°; now I am writing (11 p.m.) it is 87°, which is about the average. How you must all be shivering! The amount of perspiration we get through is something wonderful; it drops on to the paper as I write, on to the instruments as I test, and at night all the clothes get wet through with it. For all that, I feel the heat very little; in fact, were it not so unhealthy, this climate would be a most delightful one. I don’t think you need be under any apprehension about my health; if the sickness were general it would be more alarming, but it is entirely confined to one class who sleep in a particular place. The climate hitherto has agreed with me remarkably well, and I think having been before some time in the tropics enables me to stand it better. Then there is only about a week longer for us to be here, if all goes well; and if all does not go well, and we have to repair the cable, the sickly season ends next month, the Norté begins to blow, and the yellow fever disappears.

I hear a mail goes to-morrow, so I will leave off to-night and add whatever more there is to say before closing this up.

Sept. 10th.

Another man died this morning. Nothing is yet decided about our future movements. All are well on board; no fresh cases have occurred. Will write again the first opportunity to Brook Green.

| |

Believe me, |

| |

Your affectionate Brother, |

| |

PHILIP CROOKES. |

|