| History of the Tiffany Cables |

| |

When the 1858 Atlantic Cable fleet arrived in New York in late August 1858, it was the event of the century. Public interest was high, and the merchants of the city lost no time in cashing in. The cable fleet brought with it many miles of leftover cable, some of which had been submerged and recovered during the course of the expedition, and this was quickly snapped up to be made into souvenirs.

The New York Times published this report in its issue of 19 August 1858:

Chief among the merchants was Tiffany & Company, which in an advertisement published in the New York Times on 21 August claimed to have bought the entire stock:

Tiffany sold thousands of the cable samples at fifty cents each, as well as souvenirs such as “paper-weights, cane, umbrella, and whip handles, bracelets, seals and other watch-charms, festoons, and coils for ornamenting parlors and offices.”

[Charles L. Tiffany and the House of Tiffany & Co., 1893]

Tiffany brass label on 1858 cable samples

(scanned from a label applied to a cable sample)

ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH CABLE

GUARANTEED BY

TIFFANY & CO.

BROADWAY . NEW YORK . 1858

Some samples do not have

the year on the label. |

Unused label, no year. When applied to the cable, the brass label was overlapped and soldered. |

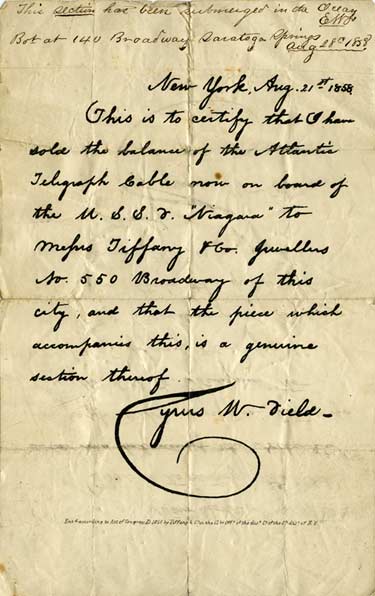

Each section of cable purchased from Tiffany was accompanied by a facsimile certificate from Cyrus W. Field authenticating the cable:

| New York, Aug 21st. 1858. |

| This is to certify that I have sold the balance of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable now on board of the U.S.S.F. “Niagara” to Messrs Tiffany & Co. Jewellers No. 550 Broadway of this city, and that the piece which accompanies this, is a genuine section thereof. |

| Cyrus W. Field. |

| |

| Ent. According to Act of Congress AD 1858 by Tiffany & Co. in the Clks. Offc. of the dist. Ct. of the Sth. dist. of N.Y. |

|

Tiffany’s souvenir pieces were distributed all across the USA; the certificate above has handwritten additions at the top:

“This section has been submerged in the Ocean"

“Bot at 140 Broadway Saratoga Springs Aug 28th 1858”

Another copy of the certificate has an embossed stamp from a jeweler in Cincinnati, and there is also one stamped at the bottom in red ink “Presented by Morris L. Hallowell & Co., Philadelphia”. Hallowell was a well-regarded Philadelphia merchant for many years.

As Tiffany had a large supply of the cable, they also wholesaled both cut and uncut lengths in the USA, and sections of the cable from other sources were sold in Britain. A number of companies advertised pieces of cable and souvenir items for sale in both countries.

But as quickly as the enthusiasm for the cable had sprung up, it vanished when the cable failed after just a few weeks of intermittent operation, and the remaining unsold pieces of cable were stored and forgotten. The New-York Historical Society has in its collection 930 pieces of Tiffany cable stored in eight of the original packing crates used for wholesale distribution.

The packing crates for Tiffany’s “$25 for 100 pieces” wholesale offer measured 3¾" H x 9" D x 10¾" W (9.5 x 22.9 x 27.3 cm) and had a lid which was nailed in place. The boxes held four layers of tightly packed cable sections, each with two rows of twelve or thirteen pieces, for a total of 100 pieces per box.

While Tiffany cable pieces are readily available today at on-line auction sites, very few of the packing crates have survived. There are eight boxes of cable at the New-York Historical Society, one of which is shown above, and one example at the Smithsonian, shown further down this page. The box immediately below is the only one presently known in a private collection, although there may be others from the 1970s find described below.

Above: Packing box with lid Above: Packing box with lid

Below: Arrangement of cable layers |

|

After the demand for cable souvenirs faded in late September 1858, many of Tiffany’s cable sections were left over, and a good number of these were stored away for the next century or more.

In 1939 All America Cables obtained an unknown number of the cable sections, which they used as a promotional item at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Each piece of cable was presented in a special box, accompanied by a reproduction of Cyrus Field's 1858 letter of authentication to Tiffany & Co.

Then in the early 1970s there are accounts of finding a large number of the cable pieces (perhaps in Vermont or New York), which variously give the year as 1973 or 1974, and the quantity as 1,200, 1,500, 2,000, and 4,000, the last described as “40 crates–100 sections to the crate.“

The results of extensive research on this re-appearance of the cables are compiled below.

|

| 4,000 Pieces of Cable |

| |

In May 1974, this news story appeared in an as-yet unidentified antiques trade paper:

4,000 Tiffany Atlantic Cable Links Found By New Yorker

About two months ago George McGowan Jr. of Lake George, N.Y. made a discovery that would make a “Tiffany” belt buckle dealer’s mouth water. He found 4,000 four-inch sections of the Atlantic telegraph cable which had been in storage since 1858. Each section of cable has a brass band around it bearing the words “Atlantic Telegraph Cable, guaranteed by Tiffany & Co., Broadway, New York, 1858”

With each section of cable was a printed document dated New York, Aug. 21, 1858, saying “This is to certify that I have sold the balance of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable now on board of the U.S.S.F. “Niagara” to Messrs Tiffany & Co. Jewellers No. 550 Broadway of this city, and that the piece which accompanies this, is a genuine section thereof..” The document is signed Cyrus W. Field.

Is this another fake reproduction item under the guise of the Tiffany name? Not so, says McGowan, who toted some sections of cable along with documents into Tiffany & Co. “We’ve heard about it,” said David Van Norman, Tiffany’s assistant manager. Furthermore, he disclosed that Tiffany has some of the cable sections in its archives, and the items are mentioned on pages 34 and 35 of the book “The Tiffany Touch.” A few have been seen in antiques shops.

The sections of cable had been stored away in 40 crates—100 sections to the crate—and for some reason were never distributed. McGowan learned about their existence from his father and promptly scooped them up. He has since sold them—for an undisclosed price, naturally—to a buyer who remains anonymous, naturally. In 1858 they sold as souvenir items of the laying of the Transatlantic telegraph cable for 50 cents apiece, although it seems the bulk of them were never offered for sale.

What are they worth today? That depends. It’s likely that the new owner will offer them for sale as historical limited editions bearing the renowned Tiffany name. Considering the prices still being asked for so-called Tiffany belt buckles, which have been proven fakes, authentic Tiffany items which are authentic antiques and authentic limited editions could command fairly high prices. We’ll just have to wait until they’re put on the market to see what kind of prices collectors are willing to pay for them.

|

| 2,000 Pieces of Cable |

| |

Two months later a double-page full-color advertisement appeared in the July 23rd 1974 issue of the Antique Trader, a widely-circulated tabloid-sized newspaper of the antiques trade in the United States. Placed by a company calling itself Lanello Reserves, PO Box 1227, Santa Barbara, California, the ad offered 2,000 pieces of the original 1858 Atlantic Cable samples which had been created by Tiffany and Company in August 1858.

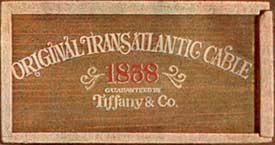

Each sample was packaged in a box marked:

Original Transatlantic Cable

1858

Guaranteed by

Tiffany & Co.

Detail of an 1974 cable box from the Lanello Reserves ad in Antique Trader |

and was accompanied by a copy of the original letter of authenticity given by Cyrus Field to Tiffany’s in 1858. While the cable sample itself was old, dating as stated to 1858, the box was made in 1974 for this promotion. It is also likely that the facsimile certificates were not ones which had survived unscathed since 1858, but were new copies, although this has not yet been verified.

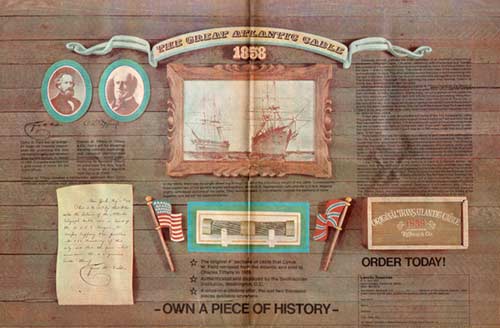

The 1974 Lanello Reserves advertisement in Antique Trader, with portraits of Cyrus W. Field and Charles L. Tiffany, a framed print of the cable-laying

ships Agamemnon and Niagara, and illustrations of the certificate,

the cable sample, and the wooden presentation box. |

After giving a short history of Cyrus Field and the laying of the 1858 cable and describing how Field sold Tiffany a length of the cable left over when the cable fleet reached New York, the ad concluded with the sales pitch:

Another “1858” cable box, made in 1974 for the Lanello promotion |

“Later Tiffany sold the remaining sections of cable to a Vermont farmer. Un-noticed, they remained there until the present. During the past year they have resurfaced and been authenticated and displayed by the Science Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The only remaining two thousand pieces of this curiosity turned antique are now being offered for the first time in over a century exclusively by Lanello Reserves. This is not just a once-in-a-century offer—but a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to own part of the original thread of communications that brought mankind closer together. Each cable is still fastened with Tiffany’s brass ferrule and is accompanied by a copy of Field’s letter of authenticity, the book The Tiffany Touch, and a handsome display box which captures the drama of the era. This is the antique that changed the course of history. Price $100 each.”

As shown above, Lanello advertised that it had presented a hundred of the pieces to the Smithsonian Institution, boasting that the cables had been “Authenticated and displayed by the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.” The cable sections presented by Lanello to the Smithsonian remain in their original wooden packing box in the museum’s permanent collection. This box is identical to those shown earlier on this page.

Although the Smithsonian’s page is titled “Tiffany Atlantic cable samples, box of 100,” a recent article by Robert Klara in Smithsonian Magazine (see link at the end of this page) quotes curator Harold Wallace as noting that only 99 pieces remain in the museum’s collection, one cable section having subsequently been donated to the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

|

|

| Images courtesy of the National Museum of American History |

There is also a section of the cable shown on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History website which has the credit line “from Silver Creations, Ltd. and Lanello Reserves Inc.” A photograph of the presentation, showing curator Bernard Finn with Richard Moskow and Randall King, appeared in the staff magazine, The Smithsonian Torch, in its issue of September 1974:

CABLE MEMENTOES–Bernard Finn (left), Curator in the Division of Electricity and Nuclear Energy of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History and Technology, examines a section of the 1858 Atlantic cable, one of 100 cable sections donated to the Museum by Richard Moskow of Silver Creations, Ltd., and Randall King (at right) of Lanello Reserves, Inc. The samples, and certificates of authenticity which accompanied them, were made up by the New York firm of Tiffany & Co. and sold to the public after contact had been successfully made between the old world and the new. The much-heralded cable broke down after a month of operation, probably accounting for the large number of Tiffany samples which survived unsold in their boxes. Certificates bore the signature of cable promoter Cyrus Field. A Field portrait from the national collections is at rear.

[Note: Prior to 1980 the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History was known as the National Museum of History and Technology.]

Silver Creations Ltd also presented a boxed section of the cable to the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (now the Powerhouse Collection) in Sydney, Australia, where the acquisition date is recorded as 27 September 1974.

Bernard Finn was the obvious person to authenticate the Tiffany cables for Lanello Reserves and Silver Creations. He was an early historian of the submarine cable industry, and had collected many artifacts for the Smithsonian after the telegraph cable stations were made obsolete in the 1960s by developments in undersea telephone cables. He was appointed Curator of Electricity at the Smithsonian in August 1962, and remained a leading expert in the field until his retirement in 2005, after which he became a Curator Emeritus of the museum.

Smithsonian Year 1968, the Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ended 30 June 1968, had this note:

Science and Technology

In June, curator Finn made a field trip to Newfoundland to investigate the early telegraph equipment still extant in the Atlantic-cable landing stations. These stations have recently been taken out of service, and Western Union International has indicated its desire to make some of the equipment available to the Museum.

The 1969 edition of the Annual Report had some further news:

Department of Science and Technology

The most important accession of the year probably is a collection of about 200 pieces of apparatus given by Western Union International

from its cable stations in Newfoundland. Together with other materials already on hand, these items give the Department an almost complete cross section of apparatus used in the hundred-year history of trans-

atlantic telegraphy.

Bernard Finn also acquired for the Smithsonian much of the equipment from the Bay Roberts cable station in Nova Scotia, and the cable industry collection formed the basis for an exhibition at the museum in 2002, now archived on line. |

| 1,500 Pieces of Cable |

| |

An advertisement from the Smithsonian (date at present unknown but probably 1975/76) offered sections of the cable to its Associates:

From the Smithsonian—A piece of history.

Left side of what is believed to be a two-page spread, as the text in the right-hand column ends in mid-sentence. The other side of the advertisement has not been located. |

The time is August, 1858. President Buchanan and Queen Victoria exchange messages. There are parades and fireworks throughout the land (and Harper’s Weekly notes that, in New York, the roof of City Hall was inadvertantly set afire). The occasion? The laying of an Atlantic Telegraph Cable linking England and the United States. Only functional for a brief time, it foreshadows complete sucess in 1866.

And Messrs. Tiffany & Co., Jewellers, purchase the balance of the cable left on board the U.S.S. Niagara for sale to the populace in souvenir lengths.

Now, after more than a century, the last 1500 of these original sections of the Atlantic Cable have been purchased by the Smithsonian Museum Shops and are available to Smithsonian Associates as truly historic mementos of an event as important to 19th Century communication as the satellite has been to the 20th Century. Each section (approximately 4”) is mounted on a handsome 7" x 9" x ¾" solid walnut plaque—accompanied by a copy of Cyrus W. Field’s letter of authentication, and a reproduction of the fascinating Harper’s Weekly 16-page...

[balance of text not available]

As noted earlier, Lanello donated 100 pieces of the cable to the Smithsonian in 1974, and these then became part of the permanent collection and would not have been offered for sale. So did Museum Shops purchase the 1,500 pieces of cable from Lanello, or did they go to the original source for their supply? No further information on this is available at present, although a number of the mounted sections on Smithsonian plaques do not have the Tiffany brass label.

“The Great Atlantic Cable” promotional flyer

from

Lanello Reserves. See below for full text of the flyer. |

Also in the 1974 issue of Antique Trader was an article about the 1858 Atlantic Cable, which described the history of how Tiffany sold the samples after the successful laying of the cable. The article included another photograph from the meeting at the Smithsonian at which Randall King of Lanello presented the cables to Bernard Finn of the National Museum of History and Technology.

Randall C. King’s name also appears in connection with an organization called the Church Universal and Triumphant. King was the third husband of Elizabeth Clare, whose second husband, the appropriately named Mark Prophet, who she married in 1963, was the founder of The Summit Lighthouse. According to this Wikipedia article, under Elizabeth Prophet’s guidance this also became known as the Church Universal and Triumphant.

Mark Prophet died suddenly of a stroke in 1973. The church now considers him to be an Ascended Master called Lanello, a combination of the names Lancelot and Longfellow, two of his previous lives. And a few months after Mark’s death, Elizabeth Prophet married an aide, the former Randall Kosp, who had changed his name to Randall C. King. The church grew rapidly in the 1970s and moved to Santa Barbara, California.

When the cable advertisement appeared in Antique Trader in 1974, Lanello Reserves of Santa Barbara, with Randall King as its president, had been set up as an offshoot of the Church Universal and Triumphant of Santa Barbara. Also in 1973-74, King, a member of the board of the church and the then-husband of Prophet, used church funds to speculate in the silver futures market, losing $697,000.

In his 2003 book, The Church Universal and Triumphant: Elizabeth Clare Prophet’s Apocalyptic Movement, Bradley Whitsel describes Lanello Reserves, Inc. as “a private, profit-making stock corporation dealing in the production, sale, and holding of gold bullion and silver coins, as well as the manufacture of processed emergency food supplies.” The company’s products were “Marketed as a prudent investment in a period of economic uncertainty and possible future food shortage...,” while “Advertising literature for the business...urged members to immediately convert their financial holdings into coins and bullion.”

Other than the details in Bradley Whitsel’s book and others exposing the practices of the Church Universal and Triumphant, there is little published information on Lanello Reserves, which was described in the Antique Trader article as “a gold and silver investment firm.”

Lanello's co-donor of the section of Tiffany cable to the Smithsonian, Silver Creations, Ltd. of Emerson, New Jersey, made and sold silver collectibles in the early 1970s, but there are no records to be found of its business activities. Nor are there any references to a connection between Silver Creations and Lanello Reserves other than in the story quoted above from The Smithsonian Torch issue of September 1974.

The Business Search section of the California Secretary of State's website [search for Lanello Reserves] lists the company as registered on 5 March 1974, but as of 11 November 2004 it is a dissolved corporation with a Montana contact address. Records at the website of the Montana Secretary of State show that the company’s incorporation was revoked on 1 November 2006, the contact address being that of The Summit Lighthouse.

It seems likely that the church’s promotion of a collectibles investment company was at the instigation of Randall King, and presumably the cable sections were purchased from either George McGowan or whoever he had sold them to. Why the church embarked on this venture remains a mystery for the moment, as does the disposal of the other 2,000 pieces found by McGowan, unless perhaps some were purchased by the Smithsonian, as noted above.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet died in Bozeman, Montana, on 15 October 2009 after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease for many years. The Church Universal and Triumphant continues to run its business... |

| 2,000 Pieces of Cable |

| |

Here is the full text of the 1974 Antique Trader article on the 1858 cable:

The Great Transatlantic Cable - 1858

Tension rose aboard the “Agamemnon” when a whale sporting in the wake nearly severed the cable |

There are some who will never forget that first day at sea. “The Agamemnon was rolling and laboring fearfully, with the sky getting darker, and both wind and sea increasing every minute. At about half-past ten o’clock, three or four gigantic waves were seen approaching the ship, coming slowly on through the mist, nearer and nearer, rolling on like green hills of water, with a crown of foam that seemed to double their height. The Agamemnon rose heavily to the first, and then went down quickly into the deep trough of the sea, falling over as she did so, to almost capsize completely on the port side. There was a fearful crashing as she lay over this way, for everything broke adrift, whether secured or not, and the uproar and confusion were terrific for a minute, then back she came again on the starboard beam in the same manner, only quicker, and still deeper than before. Here, for an instant, the scene almost defies description. Amid loud shouts and efforts to save themselves, a confused mass of sailors, boys, and marines, with deck buckets, ropes, ladders, and everything that could get loose were being hurled again in a mass across the ship to starboard.

The date was June 20, 1858. The scene was the icy Atlantic off the coast of Victorian Britain. Two of the world’s largest sailing ships were attempting a rendezvous in the middle of the Atlantic. Their seemingly impossible mission was to lay the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable, an achievement that was to revolutionize the civilized world.

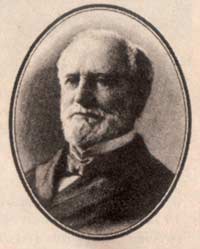

Cyrus W. Field, Esquire |

Britain and America, with their rapidly expanding trade, demanded quick and reliable communications. Britain possessed the capital and the technology necessary to support the venture of a trans-Atlantic cable. America, however, was to produce the faith and the darling, the underlying spirit behind the endeavor; for the intense vitality that made the dream of science a reality was supplied by Mr. Cyrus W. Field.

Cyrus Field was an energetic American financier who had made his fortune by the age of thirty-four and was ready for a new venture that would capture his interest. When he conceived of the possibility of spanning the Atlantic Ocean with the telegraph, the idea took strong hold of his creative imagination. It inspired him to undertake a project that tested the science and the engineering skill of the world.

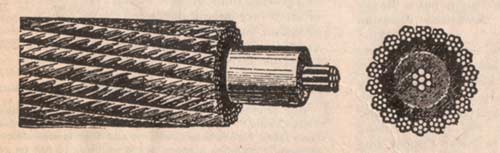

The cable itself was a unique product of nineteenth-century technology. It was designed to withstand the enormous pressures of ocean depths and resist the penetrating erosion of salt water. The core of the cable consisted of stranded copper wire coated with three layers of insulating material called gutta percha, a plastic material from the sap of certain trees native to Malaya. Over the three layers of gutta percha was woven a sheath of stranded steel. Three hundred forty thousand miles of wire and three hundred tons of gutta percha went into the manufacturing of three thousand miles of cable. The wire was enough to encircle the earth thirteen times - more than enough to reach from the earth to the moon. Once the cable had been manufactured, the next problem became one of connecting the two continents with over 2,500 miles of cable.

To a core of seven copper wires over which messages travelled, there were applied three layers of a natural insulator called gutta percha. Yarn and stranded steel wire formed the outer layer. Three hundred forty thousand miles of wire, enough to circle the earth thirteen times, were used to manufacture the first twenty-five hundred miles of cable |

In the 1850s there was not a vessel on the seas that could bear the weight of the cable. The only logical solution was to load two ships with equal amounts of cable, let them begin their mission at a point midway between the continents, and sail to the opposite shores. The United States provided the U.S.N.S. Niagara and Great Britain donated H.M.S. Agamemnon.

On July 29, 1858, after four costly failures, the two ships returned to midocean. In a final attempt to connect the hemispheres, the splice was made and the vessels parted for the last time. The Agamemnon sailed for Ireland and the Niagara was destined for Newfoundland. On August 5, 1858, each ship reached its respective destination, and the Herculean task of linking the old world with the new was successfully completed! On August 13, 1858, the directors of England relayed to the United States: “Europe and America are united by telegraphy. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, goodwill toward men!”

Once the cable lay on the ocean bed uniting the two hemispheres, it made a profound impression on the civilized world. Public recognition rose from both sides of the Atlantic. The British government expressed its intense admiration of Mr. Field. John Bright, liberal English statesman and friend of Mr. Field’s said, “The world does not know what it owes to him, and this generation will never know it.” The London Times referred to Field as “The Columbus of our time, who, after no less than forty voyages across the Atlantic in pursuit of the great aim of his life, had at length by his cable moored the New World close alongside the old.” The Great Exposition in Paris in 1867 awarded the highest distinction it had to bestow to Mr. Field and the Anglo-American and Atlantic Telegraph Companies.

But the dearest praise came from his own countrymen. Congress expressed its thanks to the great American by awarding him a gold medal in March of 1867. The Chief Justice of the United States said: “The Atlantic Telegraph is the most wonderful achievement of civilization and entitles its author to a distinguished rank among public benefactors. High upon that illustrious role will his name be placed, and here it will remain while oceans divide and telegraphs unite mankind.”

Charles Tiffany |

When the excitement was high, Charles Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & Co., of New York, determined to take advantage of the opportunity. The diamond king was in Europe when the cable touched Ireland, and he purchased from Field, twenty miles of cable that had actually been submerged and retrieved from the bottom of the ocean. Tiffany cut the cable into 4-inch lengths and fastened each with a brass ferrule. Then he sold them with an affidavit from Field attesting to their authenticity.

For over one hundred years since that time, the segments of cable have sat unnoticed in a farmer’s barn in the hills of Vermont. Their recent discovery has aroused a striking interest among collectors. Now the very same pieces of cable sold by Charles Tiffany in 1858 are back on the market!

Lanello Reserves of Santa Barbara, California, has the exclusive world rights to the two thousand remaining pieces of the cable. They are offering to interested buyers the original 4-inch sections with Tiffany’s original brass ferrule in a handsome display box that includes a copy of the certificate signed by Cyrus W. Field. Also included is a copy of the book The Tiffany Touch by John Purtell.

Cyrus W. Field looks on (from the painting) as Randall C. King, President of Lanello Reserves, presents Bernard S. Finn of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., one hundred sections of the original Atlantic telegraph cable.

Another photograph of the same scene is shown at the Smithsonian website. See above for further details. |

Lanello Reserves has donated 100 of the original 4-inch segments to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. They were received most gratefully by Mr. Bernard S. Finn, the curator of the National Museum of History and Technology and the world’s leading authority on submarine telegraphy. Authenticated by the Smithsonian, a segment of the cable is on display in a special exhibition.

Lanello Reserves, a gold and silver investment firm, specializes in unique collectibles. Mr. Randall King, president of the firm, states: “The first Atlantic cable produced not only a commercial revolution in America, but it provided a link between hearts and homes on opposite sides of the sea. It inaugurated an era of the communications between men and nations that would lead to increased friendship and peace. The story of the cable is a tale of endless battles against the elements and against the unbelief of men. It reminds us that it is only out of heroic patience and perseverance that anything truly great is born.”

Here is the full text of the Lanello Reserves flyer (typographical errors as original):

The Great Atlantic Cable

Curiously enough, perhaps the most celebrated of all mankind’s inventions is the Atlantic Telegraph Cable. The wheel came forth with little fanfare, and Telestar was greeted by the yawns of a populace made blase by reams of science fiction. But the cable—that’s a different story. The crowds on both sides of the ocean cheered and celebrated for days. The affair became so wild that a few errant fireworks ignited the roof of the New York City Hall and did considerable damage! But no one cared. The Great Atlantic Telegraph Cable spanning the ocean from Valentia, Ireland, to Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, was complete.

And none other than the illustrious Charles W. Tiffany helped fan the flames of excitement by buying an extra section of the original cable, which was first laid and then retrieved, to make souvenirs. What’s more, he cut a portion of the cable into four-inch sections and fastened each with a brass ferrule guaranteeing the authenticity and sold them with a copy of a handwritten note from Cyrus W. Field, Esq.—the hero of the day. In an apparent stroke of genius, he offered them to the public in exactly the same condition as when they came off the bottom. New York went wild! Tiffany & Co. was stormed by so many determined collectors that the police had to be called to keep peace.

It had taken over a year to complete the laying of this first transatlantic cable. The public had been treated to many a good chuckle by Cyrus Field and his crew as they reported failure after failure. The most astounding part of the whole venture was that the company kept right on trying even after it had been “scientifically” proven that electrical impulses couldn’t travel that far (2,050 miles) under that much water (over 12,000 feet)!

“The Great Atlantic Cable” promotional flyer from Lanello Reserves. |

Fortunately Field was far too busy succeeding to take note of the odds against him. On August 5, 1858, he turned in one of history’s most spectacular “they said it couldn’t be done” achievements and became a benefactor to mankind. The following morning the London Times wrote: “Since the discovery of Columbus, nothing has been done in any degree comparable to the vast enlargement which has thus been given to the sphere of human activity. More was done yesterday for the consolidation of our empire, than the wisdom of our statesmen, the liberality of our Legislature, or the loyalty of our colonists, could ever have effected.”

Later Tiffany sold the remaining sections of cable to a Vermont farmer. Unnoticed, they remained there until the present. During the past year they have resurfaced and been authenticated and displayed by the Science Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The only remaining two thousand pieces of this curiosity turned antique are now being offered for the first time in over a century exclusively by Lanello Reserves. This is not just a once-in-a-century offer—but a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to own part of the original thread of communications that brought mankind closer together. Each cable is still fastened with Tiffany’s brass ferrule and is accompanied by a copy of Field’s letter of authenticity, the book The Tiffany Touch, and a handsome display box which captures the drama of the era. This is the antique that changed the course of history. Price $100 each.

Since there are only two thousand pieces available, orders will be accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. Should your order arrive after all the cables are committed, your money will be promptly refunded. To place your order, send $100 to Lanello Reserves, P.O. Box 1227, Santa Barbara, California 93101. (805) 963-****.

|

| 1,200 Pieces of Cable |

| |

Finally, a small brochure which accompanied some of Lanello’s cable sections included the text below. All typographical errors are as in the original.

In 1972 Random House published a book entitled The Tiffany Touch, which hightlighted the cable story. In 1973 a private collector purchased a hidden treasure of 1200 cables. He donated 100 cables to the Simthsonion Institution, and 900 of the remaining cables are currently available to other collectors. Each 4" piece of Tiffany’s original cable is accompanied by the certificate from Cyrus W. Field, and is banded with the brass ferule guaranteeing its authenticity by Tiffany & Co.

|

| |

Note: The Antique Trader advertisement and the Lanello Reserves flyer above both date from 1974. The cable is no longer available from the listed address.

|

| |

In February 2024, Smithsonian Magazine published an article by Robert Klara titled “To Make Tiffany & Co. a Household Name, the Luxury Brandís Founder Cashed in on the Trans-Atlantic Telegraph Craze.”

I was pleased to be able to provide information to Mr Klara about the curious story of the cable souvenirs, and he very kindly credited the atlantic-cable.com webite in his article.

|